Tío Conejo Folktales: African Roots and Venezuelan Renditions (Part V)

Antonio Arráiz (1903-1962). Cover of Alexis Marquez Rodriguez's biography, edited by El Nacional. My copy

Tío Conejo in Arráiz’s Political Projects. Reconstructing Venezuela’s Heroic Figures.

Antonio Arráiz was a prominent poet who, with the publication of his first collection of poems, Aspero (1924), revolutionized Venezuela’s literary circles. He became the leader of the Varguardista movement and a vital reference for the future generation of poets. Why should he choose to write a book about a folk character such as Tío Conejo? The way I see it, Arráiz knew that his poetry had a limited and very selective audience and the impact on the general public was not going to transcend the intellectual circles. Besides, his intellectual audience was precisely the group of people who were the object of political persecution. They would either end up assimilated to the corrupted system, exiled, or killed. He was also moved by an artistic movement; a return to the land, to the national themes, and autochthonous characters. By appealing to the potentially heroic trickster characters of folklore, Arráiz attempted to create a figure that could deliver his message to a larger and more promising audience. For Arráiz, the best form to preserve folklore was by incorporating it into mainstream literature and adapting it to the ever-changing historical circumstances.

Source

Source

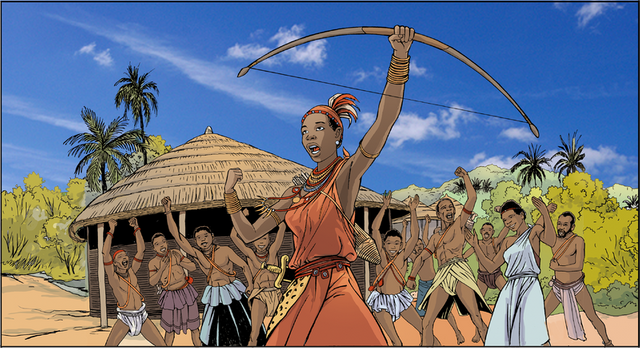

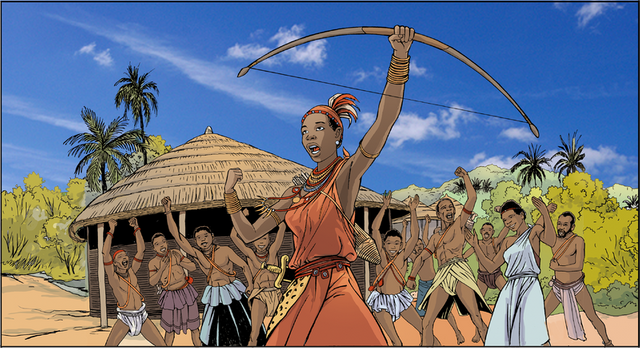

Taken from Nzinga Mbandi: Queen of Ndongo and Matamba from the UNESCO series on women in African history. Illustrations by Pat Masioni

What makes Arraiz’s work remarkable is the fact that he saw viability in using the ancient trickster characters for modern purposes. Some authors have provided insightful studies for a cross-cultural analogy in terms of the modern function of the trickster. Linda S. Chang, for instance, analyzes “the revolutionary vision of the trickster rabbit” by Angolan author Manuel Pedro Pacavira in his 1979 novel Nzinga Mbandi (37). According to Chang, Pacavira had recurred to “the sort of felicitous improvisation which is stock-in-trade of both the clever rabbit figure himself and the traditional African storyteller” in his attempt “to forge a new national identity combining the modern and the traditional” (41). In a more recent study, Crystal Anderson, argues that fiction contextualizes tricksters within a historically defined space (45). From an analysis of Gloria Naylor’s Mama Day, Anderson suggests, “Naylor’s racial strategy based on reconciliation represents one way in which the black community can retain a sense of consensus and survive” (140). Arráiz fictionalizes Tío Conejo, not only to use it as a racial strategy to promote reconciliation, but as a social class strategy to demand social change and equality for the dispossessed whose situation had been kept invariably miserable under a political system that favored inequalities and social stagnation for those who are not in a position of power.

By identifying the strengths of the working class (the clever rabbit), and the weaknesses of those in the position of power (the dumb Tigre), Arráiz attempts to stress the relationship between folklore and culture building. That is the main difference with Rivero, who tried to make folklore look as unrelated to the social world as possible. Arráiz’s promotion of the Venezuelanist sentiment should not be read as nationalist discourse. Nationalism opens up the social gaps, Venezuelanism was supposed to unite the different components of the national milieu. He highlights the beauty and wealth of the land, the absurdity of racial discrimination, and the interdependence of all the peoples who share the same sentiments toward the land.

Source

Source

In the process of transforming Tío Conejo from folklore individualistic trickster to literary community hero Arráiz not only appealed to his political resentful alter ego but to one of the characteristics of the African trickster: ambiguity. According to Pelton, “These apparent individualists become sources of community because they join the transcendent and the daily, the center and the circumference, the formed and the formless in their revelation of man himself as the confluence of the same forces that are shaping his world. They are not so much the heroes of a culture as its exemplars” (227).

Source

Source

On the one hand, Arráiz turned the character into an extension of his own self and made it perform the social and cultural duty he felt his generation was called for. As Roberts affirms, “the heroes that we create are figures who, from our vantage point of the world, appear to possess personal traits and/or perform actions that exemplify our conception of our ideal self, the self that our personal or group history, in the best of all possible worlds, has prepare us to become” (Roberts 1). On the other hand, to have things fixed, Arráiz has Tío Conejo turn things upside down first. Tío Conejo’s intervention in the lives of his peer animals is not always well received. He is seen in some tales as a chaotic element that causes more wrong than good. This situation coincides with Roberts’s discussion about figures and actions that can be considered heroic by the members of a certain group in a certain socio-historical context but can also “may be viewed as ordinary and even criminal in another context or by other groups, or even by the same ones at different times” (1). However, the chaos that results from Tío Conejo’s authority-challenging tricks is the only way he can act upon the community promoting unity and further harmony.

Source

Source

Arturo Uslar Pietri (1906-2001), Venezuelan lawyer, journalist, historian, writer, politician

Tío Conejo is portrayed as a heroic symbol of Venezuela’s cultural identity. Arráiz takes it further by implying the consequences of tricksterism contrasting with relatively permissive “viveza criolla” described by Arturo Uslar Pietri and shared by Rivero. When analyzing Juan Bobo and Pedro Rimales, the human counterparts of Tio Tigre and Tio Conejo in the Venezuelan folklore, Uslar Pietri points out that there is not moral contradiction in the fact that people’s sympathy goes with the wicked Pedro Rimales while the good Juan Bobo gets always the worse part. According to Uslar “the popular sympathy does not go with Tío Conejo’s vulnerability, but with his cleverness which is even more powerful than Tío Tigre’s strength. In Juan Bobo and Pedro Rimales’s case, the sympathy continues going with the cleverness, this time of the latter” (375). Venezuelan popular fable is then, according to Uslar, “the epic of the viveza.” “The popular sentiment,” Uslar insists, “does not care about the means the character uses to achieve his goals; what matters is the invariable triumph of cleverness, which is the weapon of the weak against the strong” (375).

By the same token, Rivero’ stories seem to support also the idea that the trickster’s actions have no repercussion on the harmony of the community or at least suggest that the trickster should not care. In Rivero’s “La Raiz,” Tío Rabipelado (Brer Possum) warns Tío Conejo that his tricks will get him into trouble. Tío Conejo ignores the Rabipelado’s advice and only laughs, ignoring the increasing negative image he is having among his peer animals. This is the image of Tío Conejo Arráiz reacted against.

The way Tio Conejo had been portrayed corresponds with the kind of hero described by Weldon (in Roberts 2). This trickster was only interested in getting personal revenge. Slaves, Roberts suggests, could have preferred this form of behavior on grounds of the fictitious sense of power it provided to their actual miserable and unredeemable lives. Arráiz suggests reading Tio Conejo as an “example of how heroic fiction serves the needs of a people in [maintaining cultural identities and values] rather than in creating a dream life” (2).

Source

Source

Arráiz challenges the “heroic culture” described by Abrahams. This heroic culture in Venezuela has been associated with Caudillismo.

By portraying Tío Tigre as the quintessential laughable authoritarian leader whose brain and vision are smaller than the smallest animal he exploits, Arráiz makes his political statement against the promotion of anti-values as heroic images that has characterized Venezuela throughout its republican history

. In this respect, Arráiz’s interest in Tío Conejo is commendable considering that “folklore should support culture-building by serving as a means of transmitting the values on which a group bases its ideal image of itself” (Roberts 4). Arráiz assumed this task as a historic-cultural duty given that Tío Conejo has been revived in different critical moments and has equally been manipulated to serve certain socio-political purposes. Governments have exploited in him different ideals, qualities, or actions that, at a given time, epitomize models of behavior people feel they need to imitate.

Thanks for your visit

Works Cited or Consulted

Anderson, Crystal S. “Far from ‘Everybody’s Everything’: Literary Tricksters in African American and Chinese American Fiction.” Diss. College of William and Mary, 2000.

Arráiz, Antonio. Tío Tigre y Tío Conejo. Caracas: Monte Ávila Editores, 1980.

Chang, Linda S. “Brer Rabbit’s Angolan Cousin: Politics and the Adaptation of Folk Material.” Folklore Forum (1986): 19:1. 36-51.

Márquez Rodríguez, Alexis. Antonio Arráiz. Biblioteca Biográfica Venezolana. El NACIONAL, 2009

Pelton, Robert. The Trickster in West Africa: A Study of Mythic Irony and Sacred Delight. Berkley: University of California Press, 1980.

Rivero Oramas, Rafael. El Mundo de Tio Conejo. Caracas: Ekaré, 1999.

Roberts, John. From Trickster to Badman: The Black Folk Hero in Slavery and Freedom. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989.

Uslar Pietri, Arturo. La Invencion de America Mestiza. Mexico: FCE, 1996.

This post got an extra 5 power for following us

Follow @elsurtidor to get biggest votes in your next posts

Thank you, guys

Hi @hlezama!

Your post was upvoted by @steem-ua, new Steem dApp, using UserAuthority for algorithmic post curation!

Your UA account score is currently 2.374 which ranks you at #18497 across all Steem accounts.

Your rank has dropped 20 places in the last three days (old rank 18477).

In our last Algorithmic Curation Round, consisting of 226 contributions, your post is ranked at #179.

Evaluation of your UA score:

Feel free to join our @steem-ua Discord server

Thanks, guys