Canaan, Sinai, Midian

Before resuming our research into the forty-two Stations of the Exodus, let us pause and ask ourselves an obvious but all-too-often neglected question: Where exactly were the Israelites going when they set out on the Exodus?

The answer to this question is surely not too hard to discover: Canaan. The Promised Land to which Moses was leading the Israelites was their native land, which Yahweh had given to Abraham and his descendants. In Genesis we read:

Now the Lord had said unto Abram, Get thee out of thy country, and from thy kindred, and from thy father's house, unto a land that I will shew thee: And I will make of thee a great nation, and I will bless thee, and make thy name great; and thou shalt be a blessing: And I will bless them that bless thee, and curse him that curseth thee: and in thee shall all families of the earth be blessed. So Abram departed, as the Lord had spoken unto him; and Lot went with him: and Abram was seventy and five years old when he departed out of Haran. And Abram took Sarai his wife, and Lot his brother's son, and all their substance that they had gathered, and the souls that they had gotten in Haran; and they went forth to go into the land of Canaan; and into the land of Canaan they came.(Genesis 12:1-5)

And later, in Exodus, we read:

And God spake unto Moses, and said unto him, I am the Lord: And I appeared unto Abraham, unto Isaac, and unto Jacob, by the name of God Almighty, but by my name Jehovah was I not known to them. And I have also established my covenant with them, to give them the land of Canaan, the land of their pilgrimage, wherein they were strangers. And I have also heard the groaning of the children of Israel, whom the Egyptians keep in bondage; and I have remembered my covenant. Wherefore say unto the children of Israel, I am the Lord, and I will bring you out from under the burdens of the Egyptians, and I will rid you out of their bondage, and I will redeem you with a stretched out arm, and with great judgments: And I will take you to me for a people, and I will be to you a God: and ye shall know that I am the Lord your God, which bringeth you out from under the burdens of the Egyptians. And I will bring you in unto the land, concerning the which I did swear to give it to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob; and I will give it you for an heritage: I am the Lord.(Exodus 6:2-8)

This answers our question, but it immediately prompts another question: If the Israelites were returning to Canaan, why did they spend so long wandering in the Sinai desert?

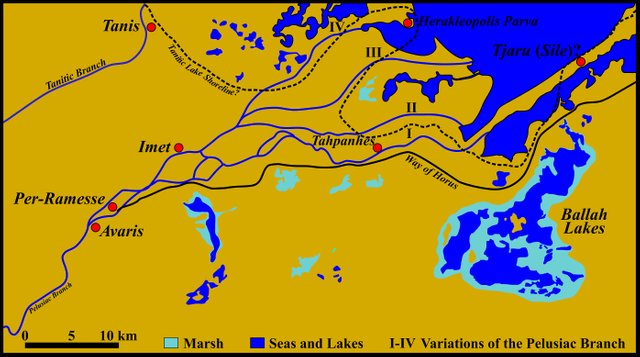

At the time of the Exodus, there was a perfectly good road that led straight from the Nile Delta into Canaan. The Egyptians knew this road as the Way of Horus. In the Bible, it is called the Way of the Land of the Philistines:

And it came to pass, when Pharaoh had let the people go, that God led them not through the way of the land of the Philistines, although that was near; for God said, Lest peradventure the people repent when they see war, and they return to Egypt: But God led the people about, through the way of the wilderness of the Red sea: and the children of Israel went up harnessed out of the land of Egypt. (Exodus 13:17-18)

This is a curious explanation for the circuitous route which the Israelites took. God feared that if they were faced with the prospect of having to fight their way through Philistia, they would lose heart and return to Egypt. But one could hardly describe their passage through the wilderness of Sinai as a peaceful one. Several times in the course of their wanderings they were obliged to take up arms against formidable enemies: the Amalekites (Ex 17:8-16), the Aradites (Numbers 21:1-3), the Ammonites (Nu 21:21-27), the Bashanites (Nu 21:33-35), and the Midianites (Numbers 31). And when they finally crossed the Jordan and entered Canaan, they immediately embarked upon a campaign of conquest that lasted about seven years (Ussher §§302-322). What’s more, in following this circuitous route, the Israelites were not deterred from losing heart and murmuring against Moses. In fact, in the very next chapter after the one quoted above, we are told:

But the Egyptians pursued after them, all the horses and chariots of Pharaoh, and his horsemen, and his army, and overtook them encamping by the sea, beside Pihahiroth, before Baalzephon. And when Pharaoh drew nigh, the children of Israel lifted up their eyes, and, behold, the Egyptians marched after them; and they were sore afraid: and the children of Israel cried out unto the Lord. And they said unto Moses, Because there were no graves in Egypt, hast thou taken us away to die in the wilderness? wherefore hast thou dealt thus with us, to carry us forth out of Egypt? Is not this the word that we did tell thee in Egypt, saying, Let us alone, that we may serve the Egyptians? For it had been better for us to serve the Egyptians, than that we should die in the wilderness. (Exodus 14:9-12)

So there is clearly something amiss with the explanation we are given for the circuitous route. I believe, however, that it preserves a trace of the true reason that the Israelites were forced to take a roundabout route to Canaan: war was, indeed, the crux of the matter, but not a possible war with the Philistines.

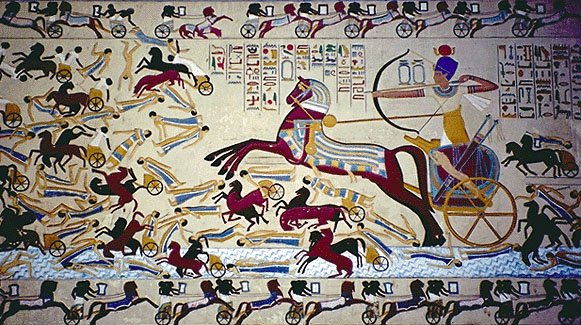

Egyptians and Hyksos

In the version of the Short Chronology which I have been espousing in these and other articles, the Exodus is regarded as an historical event that took place at the end of the Hyksos Period of Egyptian history. The Hyksos were the Imperial Assyrians, who had ruled over Egypt for several decades. They were finally expelled by the Pharaoh Ahmose I, the founder of the 18th Dynasty. As a working hypothesis, I am following the chronology of Charles Ginenthal, who placed the Exodus in the year 763 BCE (Ginenthal 542).

After liberating the Delta region from the Hyksos, Ahmose pursued them into southern Canaan, where he besieged the city of Sharuhen for six years (Breasted 1906:2:4-5). The precise location of Sharuhen is still disputed, but Tel Heror, 20 km southeast of Gaza City, is a leading candidate. Other candidates are Tell el-Farah (South) and Tell el-Ajjul, both of which are in the same area. If Sharuhen was not actually on the Way of Horus, it was very close to it.

When, therefore, the Israelites set out along the Way of Horus, they were heading into a major theatre of war. This, I believe, is the correct interpretation of that passage in the Bible in which God does not lead them to Canaan “through the way of the land of the Philistines ... Lest peradventure the people repent when they see war, and they return to Egypt.” It seems clear to me that the Israelites did set out in this direction before being forced to turn about and retrace their steps. In Exodus, we read:

And the Lord spake unto Moses, saying, Speak unto the children of Israel, that they turn and encamp before Pihahiroth, between Migdol and the sea, over against Baalzephon: before it shall ye encamp by the sea. (Exodus 14:1-2)

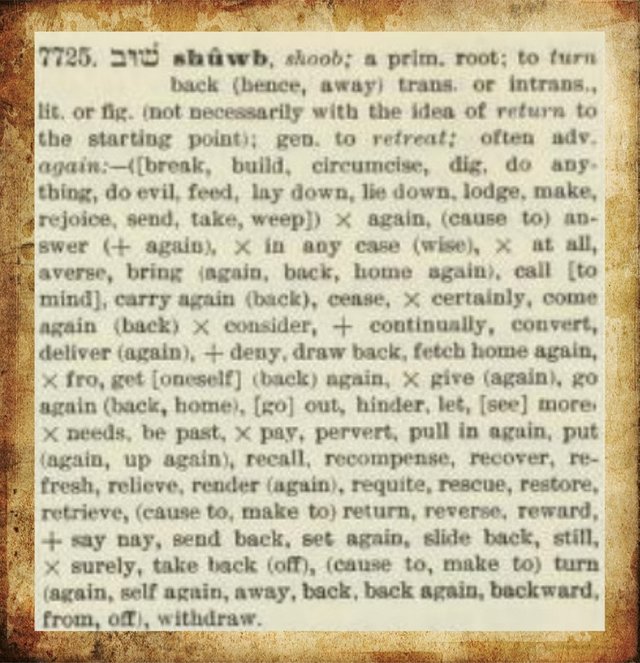

In Young’s Literal Translation of the Bible, this passage reads:

And Jehovah speaketh unto Moses, saying, “Speak unto the sons of Israel, and they turn back and encamp before Pi-Hahiroth, between Migdol and the sea, before Baal-Zephon; over-against it ye do encamp by the sea ... (Exodus 14:1-2)

Most translations translate the Hebrew וְיָשֻׁ֗בוּ (wə·yā·šu·ḇū) as turn back. The Israelites were in retreat.

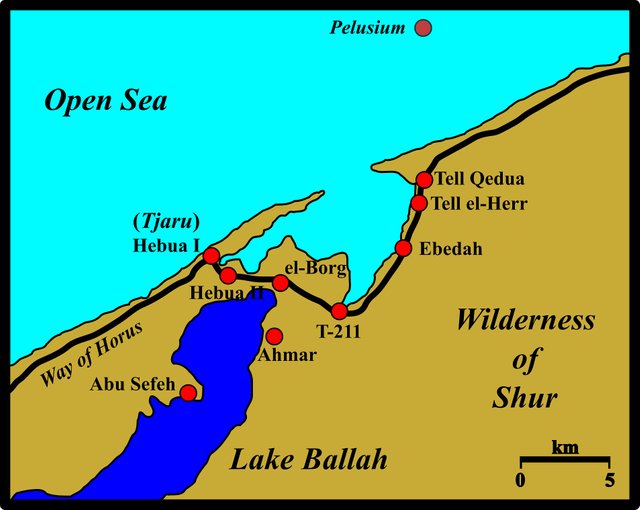

It is possible that when the Israelites reached Tjaru, the Egyptian frontier post which I have identified with Etham (the 3rd Station of the Exodus), they were confronted by the garrison that Ahmose had stationed there, or even by the rearguard of Ahmose’s army, and forced to beat a hasty retreat. Their subsequent escape across the Yam Suph (which I have identified with Lake Ballah) into the Wilderness of Shur could very well have been the act of desperation that is described in Scripture.

A Change of Mind

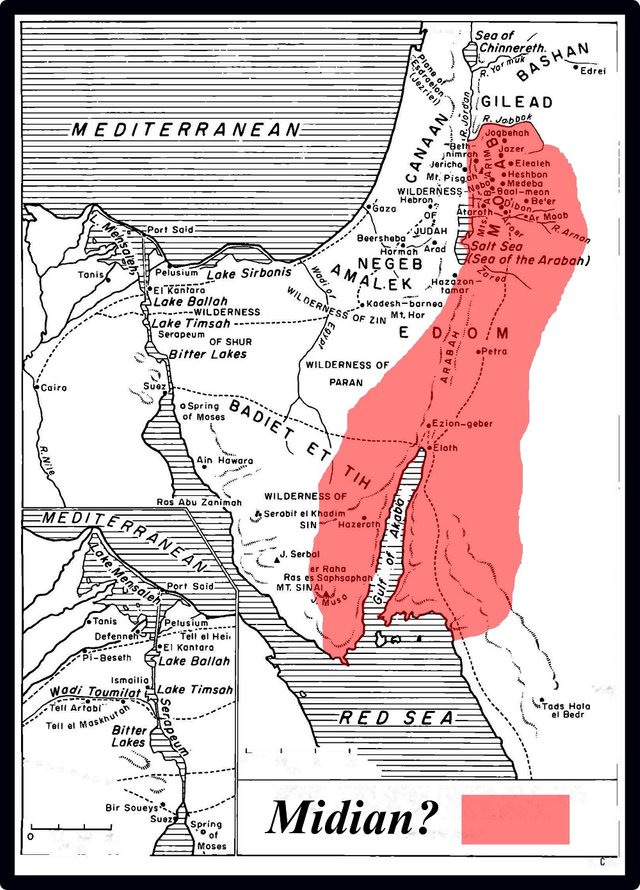

With the Way of Horus closed to them, the Israelites needed a new plan. I believe it was at this point that Moses decided to make for Midian, the home of his father-in-law—either as a temporary refuge until the road to Canaan was safe or as an alternative homeland for the Israelites. According to the Book of Exodus, Moses was well acquainted with the land of Midian, which is thought to have lain along the eastern shore of the Gulf of Aqaba:

And it came to pass in those days, when Moses was grown, that he went out unto his brethren, and looked on their burdens: and he spied an Egyptian smiting an Hebrew, one of his brethren. And he looked this way and that way, and when he saw that there was no man, he slew the Egyptian, and hid him in the sand. And when he went out the second day, behold, two men of the Hebrews strove together: and he said to him that did the wrong, Wherefore smitest thou thy fellow? And he said, Who made thee a prince and a judge over us? intendest thou to kill me, as thou killedst the Egyptian? And Moses feared, and said, Surely this thing is known. Now when Pharaoh heard this thing, he sought to slay Moses. But Moses fled from the face of Pharaoh, and dwelt in the land of Midian: and he sat down by a well. (Exodus 2:11-15)

In Midian, Moses was befriended by a priest called Reuel (Ex 2:18) or Jethro (Ex 3:1), whose daughter Zipporah he married. Zipporah bore him two sons, Gershom and Eliezer. According to tradition, Moses dwelt in Midian for forty years between the ages of 40 and 80 (Acts of the Apostles 7:23-30, Exodus 7:7).

In the Bible, it is never explicitly stated that Moses and the Israelites visited Midian during the Exodus. There are, however, several hints that they passed through Midian on their way to Canaan:

Exodus 18: Jethro meets with Moses in the wilderness at the “Mountain of God”.

Numbers 22:4 ... 7: Moab was afraid of the sons of Israel; he said to the elders of Midian, “Here is a horde now cropping everything around us as an ox crops the grass of the fields” ... The elders of Moab and the elders of Midian set out ...

Numbers 25: Yahweh spoke to Moses and said, “Harry the Midianites and strike them down, ·for they have harassed you with their guile in the Peor affair and in the affair of Cozbi their sister, daughter of a prince of Midian, the woman who was killed the day the plague came on account of Peor.”

Numbers 31: The Israelites wage a Holy War against the Midianites.

During the Exodus, Moses and the Israelites had more contact with the Midianites than one would have expected.

Midian

But where was Midian? Traditionally, it is located along the eastern shore of the Gulf of Aqaba, but this is not at all certain. In The Jewish Encyclopedia, we read of the Midianites:

Their geographical situation is indicated as having been to the east of Palestine; Abraham sends the sons of his concubines, including Midian, eastward (Gen. xxv.6). But from the statement that Moses led the flocks of Jethro, the priest of Midian, to Mount Horeb (Ex. iii. 1), it would appear that the Midianites dwelt in the Sinaitic Peninsula. Later, in the period of the Kings, Midian seems to have occupied a tract of land between Edom and Paran, on the way to Egypt (I Kings xi. 18). Midian is likewise described as in the vicinity of Moab: the Midianites were beaten by the Edomite king Hadad “in the field of Moab” (Gen. xxxvi. 35), and in the account of Balaam it is said that the elders of both Moab and Midian called upon him to curse Israel (Num. xxii. 4, 7). Further evidences of the geographical position of the Midianites appear in a survey of their history. (Singer 547)

The fact that Moses grazed the flocks of Jethro near Horeb is surely significant. We are told this in the account of the burning bush:

Now Moses kept the flock of Jethro his father in law, the priest of Midian: and he led the flock to the backside of the desert, and came to the mountain of God, even to Horeb. (Exodus 3:1)

This suggests that Horeb—Mount Sinai, or the Mountain of God—lay in or close to Midian. This is also implied by the fact that Jethro encounters Moses and the Israelites at the Mountain of God during the Exodus:

And Jethro, Moses’ father in law, came with his sons and his wife unto Moses into the wilderness, where he encamped at the mount of God: (Exodus 18:5)

The passage seems to imply that Jethro travelled from Midian to the Mountain of God expressly to meet with Moses. But how could Jethro have known about the Exodus or the route that Moses was following? A much more reasonable explanation is that Jethro’s home in Midian was in the vicinity of the Mountain of God, and that Moses went there expressly to meet with him.

But even if we accept this as fact, we cannot use it to fix the location of Midian unless we already know the location of Horeb—and vice versa. In short, Midian could be located in several places:

In Sinai to the west of the Gulf of Aqaba.

In Arabia to the east of the Gulf of Aqaba.

In the vicinity of Edom to the north of the Gulf of Aqaba.

In the vicinity of Moab to the east of the Dead Sea.

Perhaps Midian encompassed all four regions at one time?

The Road to Midian

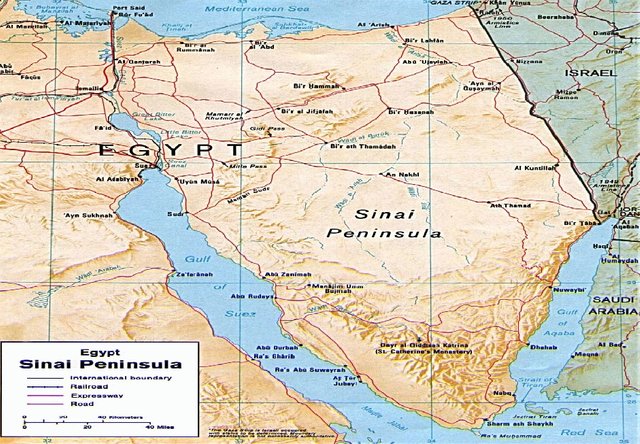

Whether Midian was on the western or eastern shore of the Gulf of Aqaba, or even further north in Edom or Moab, the Israelites would have been obliged to cross the Sinai Peninsula in order to reach it. In Ptolemaic and Roman times, there was a major road that ran across the peninsula from Clysma (Suez) to Elath (Aqaba). This thoroughfare was known as the King’s Highway. At the time of the Exodus, however, the northern end of the Gulf of Suez lay much farther north than it does today—possibly as far north as the site of the modern city of Ismailia on the northern shore of Lake Timsah—and Clysma did not exist.

So what route would Moses have chosen if he was making for Jethro’s home in Midian? In the Book of Numbers, when the Israelites are in the city of Kadesh in the Wilderness of Zin, we are told:

And Moses sent messengers from Kadesh unto the king of Edom, Thus saith thy brother Israel, Thou knowest all the travail that hath befallen us: How our fathers went down into Egypt, and we have dwelt in Egypt a long time; and the Egyptians vexed us, and our fathers: And when we cried unto the Lord, he heard our voice, and sent an angel, and hath brought us forth out of Egypt: and, behold, we are in Kadesh, a city in the uttermost of thy border: Let us pass, I pray thee, through thy country: we will not pass through the fields, or through the vineyards, neither will we drink of the water of the wells: we will go by the king’s high way, we will not turn to the right hand nor to the left, until we have passed thy borders. (Numbers 20:14-17)

This implies that the King’s Highway existed in some form at the time of the Exodus. It is also significant that an important event at Kadesh in the Wilderness of Zin, in which Moses strikes a rock to bring forth water, is very reminiscent of a similar episode that takes place at Rephidim in the Wilderness of Sin (Exodus 17:1-7). The Wilderness of Sin and Rephidim are the 8th and 11th Stations of the Exodus, while Kadesh is the 33rd. We must be prepared to accept that the Wilderness of Sin and the Wilderness of Zin were one and the same desert and that these are two different accounts of the same event.

Perhaps Jethro lived in Kadesh?

A Working Hypothesis

So, where does all this leave us? Tentatively, I offer the following hypothesis:

The Exodus took place in 763 BCE, in the same year as the Expulsion of the Hyksos (ie Assyrians) from Egypt and the establishment of the 18th Dynasty by Ahmose I.

Moses’ first intention was to return to Canaan by the shortest and most direct route: along the Way of Horus, the principal road that ran along the coast from the northeastern Delta to southern Canaan.

The Israelites set out from the neighbourhood of the Hyksos capital Avaris, on the site of which the later city of Rameses was built. This is the first Station of the Exodus, referred to anachronistically in the Bible as Rameses.

The Israelites initially travelled along the Way of Horus towards Canaan. The second Station of the Exodus, Succoth, lay somewhere in the vicinity of the later city of Tahpanhes (Daphnae), about 30 km northeast of Avaris.

The third Station, Etham, was the fortress of Tjaru, about 30 km further east.

At this point in the Exodus, the Israelites were forced to turn back. After expelling the Hyksos from the Delta region, Ahmose had pursued them into southern Canaan and besieged them in the southern Canaanitic settlement of Sharuhen. The Israelites, therefore, were marching into a war-zone. This was why they were forced to turn around and retrace their steps—possibly pursued by Egyptian troops from Tjaru.

I believe that Moses now formed a new plan. Instead of going to Canaan, he would lead the Israelites to Midian, the home of his father-in-law, Jethro. He may have decided that Midian was just as good a place for the Israelites to settle as Canaan, or it may have been his intention to simply sojourn in Midian until the road to Canaan was safe and the Exodus could be resumed. This explains why the Israelites now headed into Sinai: they were making their way to Midian.

Jethro’s home in Midian lay in the vicinity of the Mountain of God.

The Wilderness of Sin and the Wilderness of Zin were one and the same place.

Conclusion

As we attempt to trace the subsequent path of the Exodus, we should bear in mind the possibility that the Israelites were now making for Midian, not Canaan. We should also keep our minds open as to the location of Midian in those days. We may have to revisit some of the earlier Stations of the Exodus in the light of new discoveries.

To be continued ...

References

- James Henry Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, Volumes 1-5, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1906)

- Charles Ginenthal, Egypt and Palestine, Pillars of the Past, Volume 3, Forest Hills, New York (2010)

- Isidore Singer (managing editor), The Jewish Encyclopedia, Volume 8, Funk & Wagnalls Co, New York (1905)

- James Strong, The Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible, Eaton & Mains, New York (1890)

- James Ussher, Larry and Marion Pierce (editors), The Annals of the World, Revised and Updated from the 1658 English Translation, Master Books, Green Forest, AR (2003)

Image Credits

- Egypt: Sinai Peninsula: University of Texas Libraries, Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, Public Domain

- The Way of Horus: Adapted from Figure 1: Historical Landscape of the Northeastern Nile Delta, © Bietak & Forstner-Müller, Fair Use

- The Way of Horus: © James K Hoffmeier, Fair Use

- Ahmose Expels the Hyksos from Egypt: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

- Strong’s Hebrew 7725: James Strong, The Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible, Eaton & Mains, New York (1890), Public Domain

- Midian?: M Celle (designer), Alexander Jones (General Editor), The Jerusalem Bible: Reader’s Edition, Doubleday & Company Inc, Garden City NY (1968), Fair Use