Kimble [Kimball] Bent An Unusual European Who Deserted The British Army And Joined The Hau Hau #8

One day in the spring of 1866, when Tito and his hapu, [sub tribe] their bird-hunting expeditions over for the season, were gathered in their bush-village Rimatoto, three strange Maoris, fully armed, entered the settlement.

They had travelled overland from the King Country, far to the north, on a mission from Tawhiao, the Waikato King, who, after the conquest of the Waikato Valley by the white troops, had taken refuge with the Ngati-Maniapoto tribe.

The envoys had been sent down to recover some Waikato war-flags which were in the possession of the Taranaki Hauhaus.

In the crowded whare puni [meeting house] that night, when the Waikato warriors made their errand known, one of them caught sight of the white man, sitting silently in his corner, and asked who he was. When Tito explained, the visitor asked,

“Why don't you kill him?”

“He is my pakeha,” said Tito, “and I will protect him, because our prophet Te Ua has tapu'd him,[made his sacred] and ordered us not to harm him.”

“That is indeed a soft and foolish way to deal with pakehas,” exclaimed a fierce-looking young warrior, one of the Waikato trio. “We don't take any white prisoners in our country. You ought to have his head stuck on the fence of your pa.”

Tito laughed. “Ringiringi is going to be useful to us,” he said. “Besides, he is a Maori now.”

Next morning Tito despatched the white man and an old Maori named Te Waka-tapa-ruru through the forest to Te Putahi, a stockaded village some ten miles away, on the banks of the Whenuakura River, with a message to the people of that pa requesting them to return the colours for which the king had sent.

This mission accomplished, Bent stayed a while in Te Putahi, where he was treated with much kindness, because of his association with Tito.

On the morning after his arrival, a man came to his sleeping-hut and, without saying a word, placed on the mat before him a couple of blankets and a watch.

The history of the watch was afterwards explained to him by Te Waka-tapa-ruru.

This warrior was a typical old bush-fighter.

He had a very big head; he was tattooed on the cheeks; he was wiry and wonderfully quick on his legs.

He told Bent, with a devilish grin on his corrugated face, that the watch had belonged to a white man, called Paratene, whom he, Te Waka, had shot the previous year at Otoia, on the Patea River.

This pakeha was Mr C. Broughton, a native interpreter who had been sent on a special Government mission to the Hauhaus, and was barbarously murdered while in the act of lighting his pipe in the village marae.

Broughton's slayer, despite his repulsive antecedents, became a friend of Bent's, and they were close comrades until 1869 when the old man was killed in the act of charging furiously on the Armed Constabulary at the attack on the Papa-tihakéhaké stockade.

At Te Putahi “Ringiringi” was astonished to find another white man, clothed like himself in a blanket.

This man walked up and greeted him, and the pakeha-Maori recognised the long-haired, rough bearded fellow as an old fellow-soldier.

His name was Humphrey Murphy; he, too, had been a private in the 57th, and had become as dissatisfied with the life as Bent had done, and deserted to the Hauhaus.

Bent sums him up as “a bad lot.” Murphy was an evil-tempered Irishman, faithful to neither white man nor Maori.

He belonged to two chiefs, Te Onekura and Whare-matangi, who lived in the pa at Te Putahi.

Murphy, it appeared from his own story, had been taken over as a taurekareka, a slave, by one of the Hauhau chiefs when he deserted and had been sent as a food-carrier to Te Putahi by his owner, who treated his “white trash” with scant consideration.

At Te Putahi he had been taken over by the two local chiefs.

The deserter bragged to Bent, as they sat side by side on the village marae, that he would shortly return to his old Maori “boss,” as he called him, and kill him, and take what money he could find as payment for his enforced labour.

While Murphy was speaking, a young Maori girl sat by quietly listening.

When the runaway soldier rose and walked off to his hut, the girl said,

“Ringi, I heard what that taurekareka white man was saying. I have learned enough of the pakeha's tongue to know that he is going to kill his rangatira and steal his money.”

“Kaati Don't say a word about it,” cautioned Bent.

But the girl rose up in the meeting-house one night after “Ringiringi” had departed to his home at Rimatoto, and repeated the threat she had overheard from Murphy's lips.

That settled the taurekareka's fate.

Bent, sometime later, inquiring after Murphy from one of Tito's men who had been on a visit to Te Putahi, was told that he had been killed.

The Hauhaus had a short way with such as he.

He was quietly tomahawked one night as he lay asleep, and his despised remains dragged out and cast into the Whenuakura River that ran below the village.

At this time there were at least four white men living with the Hauhaus in South Taranaki.

One came to Rimatoto to see “Ringiringi,” and remained with him for a week.

His name was Jack Hennessy, and he had, like Bent, deserted from the 57th Regiment.

He was, in fact, the “shut-eye sentry” who had seen Bent steal off from the Manawapou camp in 1865.

He gave himself up to the white forces sometime later, tired of living with the Hauhaus, and was court-martialled and sent to prison.

Another summer came, and the crops were gathered in, and the men of Tito's hapu, after nearly a year of comparative peace, wearied for the war-path again.

Rimatoto and other small bush-hamlets were deserted, and the tribes gathered in, bearing their food supplies to the Hauhau council-village of Taiporohenui, close to where the town of Hawera now stands.

Taiporohenui was a famous name, a word of mana, [power] as the Maori would say, amongst all the tribes from Whanganui to Waikato.

The name, say the wise men of Taranaki, goes back far beyond the days of the later Maori migration to New Zealand, in the canoes Aotea, Tokomaru, Tainui, and other Polynesian Viking ships.

It was that of a great temple in Tahiti, in the tropic isles of the Hawaiikian seas, countless generations ago. and in this latter-day Taiporohenui the Maoris, mindful of their ancient traditions, built another temple.

This Hauhau praying-house and council-hall, constructed of hewn timber with raupo-reed walls and nikau-thatch roof, is described by Bent as the largest building of native construction that he had seen.

It was about one hundred and twenty feet in length, and was of such exceptional size that the ridge-pole was supported by four poutoko-manawa, or pillars, instead of one or two, as in the ordinary Maori meeting-house.

There were five fires burning in it at night, in the stone fireplaces down its long central aisle, on either side were the mat-covered resting places of the people.

The timbers of the house were of the durable totara pine.

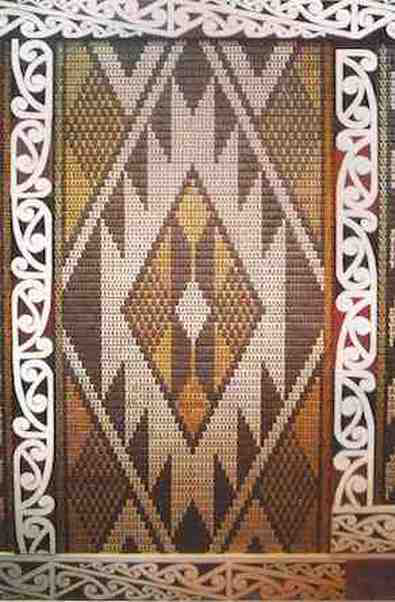

The inside was lined with beautiful tukutuku work,

of kakaho reeds and thin wooden lathes artfully fastened with kiekie fibre, arranged in

many handsome geometrical patterns.

Beneath the first large poutoko-manawa in the house was buried a large piece of greenstone in the rough, the whatu, or “luck-stone,” of the sacred house.

It was the Maori custom when the centre-pole of a large meeting-house or the first big palisade-post of a fort was set in position, to place a piece of greenstone, often in the form of an ornament, such as an ear-drop or a carved tiki, at its foot.

[We have survivals of this widespread ancient custom amongst ourselves, in the practice of placing coins, etc., under the foot of a mast of a new ship, and under the foundation-stone of a church or other important building. The cult is found amongst many savage nations in its primitive form.

Here is an instance narrated by Mr. T. C. Hodson in an article in Folk-Lore (Vol. XX., No. 2, 1909) on “Head-hunting amongst the Hill-tribes of Assam”,

“The head-man of a large and powerful village (on the frontier of the State of Manipur) was engaged in building himself a new house, and to strengthen it had seized this man (a Naga) and forcibly cut off a lock of his hair, which had been buried underneath the main post of the house. In olden days the head would have been put there, but by a refinement of some native theologian a lock of hair was held as good as the whole head.”

It was the olden Maori custom to place a human head beneath the central pillar of a sacred building, and to have a human sacrifice at the opening of a new house.]

In front of the great house on the marae, or village square, stood the sacred Niu-pole, a totara pine flagstaff, nearly fifty feet in height, with a yard about fourteen feet long, the staff was stayed like the mast of a ship.

The war-flags of the Hauhaus were flown from the Niu, and the people daily marched around its foot in their “Pai-mariré” procession, intoning the chants their prophet had taught them.

This Niu was one of the first worship-poles planted in Taranaki by the Hauhau prophet's command, and it was the centre of many a wild fanatic gathering.

At its foot there was planted a large piece of unworked greenstone, as was done when the first house-pillar was set up—as the whatu of the sacred pole, this block of pounamu is still there, says Bent.

Round this staff of worship, where the bright war flags hung, the people marched daily in their strange procession, chanting their wild psalms.

Tito te Hanataua was one of the priests of the Niu, and he led his tribe in the services after the Hauhau religion.

Some of the chants were amazing mixtures of English and Maori, some were all pidgin-English, softened by the melodious Maori tongue.

Here is a specimen of the daily chants, intoned by all the people as they marched round and round the holy pole.

The priest shouted,

“Porini, hoia” (“Fall in, soldiers”),

then “Teihana” (“Attention!”),

and they stood waiting.

Then they chanted, as they got the order to march,

Translation.

Kira Kill

Wana One

Tu Two

Tiri Three

Wha Four

Teihana Attention

Round the sacred flag-staff they went, men, women, and children, chanting,

Rewa River

Piki rewa Big river

Rongo rewa Long river

Tone Stone

Piki tone, Big stone,

Teihana Attention

Rori Road

Piki rori Big road

Rongo rori Long road

Puihi Bush

Piki puihi Big bush

Teihana Attention

Rongo puihi Long bush

Rongo tone Long stone

Hira Hill

Piki hira Big hill

Rongo hira Long hill

Teihana Attention

Mauteni Mountain

Piki mauteni Big mountain

Rongo mauteni Long mountain

Piki niu Big staff

Rongo niu Long staff

Teihana Attention

Nota North

No te pihi North by East

No te hihi N. Nor'-east

Norito mino N.E. by North

Noriti North-east

Koroni Colony

Teihana Attention

Hai Hi

Kamu te ti Come to tea

Oro te mene All the men

Rauna Round

Te Niu The Niu

Teihana Attention

Hema Shem

Rurawini Rule the wind

Tu mate wini Too much wind

Kamu te ti Come to tea

Teihana Attention

And so on, a marvellous farrago of Maorified English words and phrases.

It was Te Ua's “gift of tongues,” they imagined, that had descended upon them.

Night and morning, too, the sound of Hauhau prayers rose from the great camp.

Here is one, the “Morning Song” (“Waiata mo te Ata”), in imitation of the English Prayer-book,

Translation.

Koti te Pata, mai marire; God the Father, have mercy on me;

Koti te Pata, mai marire; God the Father, have mercy on me;

Koti te Pata, mai marire; God the Father, have mercy on me;

To rire, rire: Have mercy, mercy (or peace, peace)!

Koti te Tana, mai marire; God the Son, have mercy on me;

Koti te Tana, mai marire; God the Son, have mercy on me;

Koti te Tana, mai mariré; God the Son, have mercy on me;

To rire, rire: Have mercy, mercy

Koti te Orikoli, mai marire; God the Holy Ghost, have mercy on me;

Koti te Orikoli, mai marire; God the Holy Ghost, have mercy on me;

Koti te Orikoli, mai marire; God the Holy Ghost, have mercy on me;

To rire, rire: Have mercy, mercy

To mai Niu Kororia, mai marire; My glorious Niu, have mercy on me;

To mai Niu Kororia, mai marire; My glorious Niu, have mercy on me;

To mai Niu Kororia, mai marire; My glorious Niu, have mercy on me;

To rire, rire Have mercy, mercy

The more warlike chants ended in a loudly barked “Hau” the watchword and holy war-cry of the rebel bushmen.

Very wild they were, these savage hymns, haunting in rhythm, and stirring the people to a frenzy of fanatic fire.

Kimble Bent joined in these Hauhau war-rites like any Maori, and marched, chanting with his wild comrades, round and round the Niu.

Several skirmishes between the whites and Maoris occurred in the winter and early spring of 1866, and one of these had some concern for the exile.

About three miles away from Taiporohenui was a village called Pokaikai, to which “Ringiringi” was sent awhile by his chief.

While he was there the prophet Te Ua arrived.

He dreamed a dream, one of bad omen, and he straightway counselled “Ringiringi” to return at once to Taiporohenui. “Ringi” obeyed.

Three days, or, rather, three nights afterwards, a force of colonial soldiers under Colonel McDonnell unexpectedly attacked Pokaikai and rushed the village, killing several Hauhaus.

In some way, the Forest Rangers under McDonnell had heard that the deserter Kimble Bent was in Pokaikai, and they were eager to capture or shoot him.

Some of them surrounded one of the whares [houses] in which they imagined Bent was sleeping.

A young volunteer named Spain had just previously, unnoticed by them, gone into the whare to bring out a dead Hauhau, and while he was there the Rangers, hearing someone say there was a white man within, fired a volley into the hut, which unfortunately mortally wounded Spain.

This young soldier was the only pakeha killed in the fight.

When “Ringiringi” heard of the Pokaikai affair from the fugitives who fled through the bush to Taiporohenui, he felt that the Hauhau prophet had indeed been his good angel, for it was only Te Ua's injunction to return to the main Hauhau camp that had saved him from the vengeful bullets of his fellow whites.

And thenceforward the white man was a dreamer of many a strange dream, and he came to believe almost as implicitly as the forest-men themselves in the omens that lay in the visions of the night, and in warning voices from the spirit-world.

About this time “Ringiringi” changed hands, much as if he were a fat porker or a keg of powder or any other article of Maori barter.

Rupe (“Wood-pigeon”), a chief of Taiporohenui, made a request of Tito, to whom he was related, for his pakeha mokai, his tame white man.

He had never owned a pakeha, he explained, and would like one all to himself, and he knew that “Ringiringi” would be a handy man to have around, to keep his armoury of guns, of miscellaneous makes and dates, in repair, and to make cartridges for him.

The first of the below posts has a list of the previous posts of Maori Myths and Legends

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/how-war-was-declared-between-tainui-and-arawa

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-curse-of-manaia-part-1

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-curse-of-manaia-part-2

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-legend-of-hatupatu-and-his-brothers

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/hatupatu-and-his-brothers-part-2

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-legend-of-the-emigration-of-turi-an-ancestor-of-wanganui

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-continuing-legend-of-turi

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/turi-seeks-patea

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-legend-of-manaia-and-why-he-emigrated-to-new-zealand

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-love-story-of-hine-moa-the-maiden-of-rotorua

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/how-te-kahureremoa-found-her-husband

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-magical-wooden-head

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-art-of-netting-learned-from-the-fairies

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/te-kanawa-s-adventure-with-a-troop-of-fairies

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-loves-of-takarangi-and-rau-mahora

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/puhihuia-s-elopement-with-te-ponga

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-story-of-te-huhuti

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-trilogy-of-wahine-toa-woman-heroes

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-modern-maori-story

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/hine-whaitiri

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/whaitere-the-enchanted-stingray

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/turehu-the-fairy-people

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/kawariki-and-the-shark-man

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/awarua-the-taniwha-of-porirua

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/hami-s-lot-a-modern-story

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-unseen-a-modern-haunting

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-death-leap-of-tikawe-a-story-of-the-lakes-country

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/paepipi-s-stranger

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-story-of-maori-gratitude

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/by-the-waters-of-rakaunui-1

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/by-the-waters-of-rakaunui-2

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/bt-the-waters-of-rakaunui-3

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/bt-the-waters-of-rakaunui-4

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/te-ake-s-revenge-1

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/te-ake-s-revenge-2

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/te-ake-s-revenge-3

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/te-ake-s-revenge-4

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/some-of-the-caves-in-the-centre-of-the-north-island

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-man-eating-dog-of-the-ngamoko-mountain

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-story-from-mokau-in-the-early-1800s

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/new-zealand-s-atlantis

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-cave-dwellers-of-rotorua

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/kawa-mountain-and-tarao-the-tunneller

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-legend-of-fragrant-leaf-s-rock

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-tale-from-the-waikato-river

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/uneuku-s-judgment

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/at-the-rising-of-kopu-venus

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/harehare-s-story-from-the-rangitaiki

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/another-way-of-passing-power-to-the-successor

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-cave-of-wairaka

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-tale-of-how-mount-tauhara-got-to-where-it-is-now

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/te-ana-o-tuno-hopu-s-cave

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/stories-of-an-enchanted-valley-near-rotorua

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/utu-a-maori-s-revenge

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/where-tangihia-sailed-away-to

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-curse-on-te-waru-s-new-house

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-fall-of-the-virgin-s-island

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-first-day-of-removing-the-tapu-on-te-waru-s-new-house

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-maori-detective-story

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-second-day-of-removing-the-tapu-on-te-waru-s-new-house

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-story-of-a-maori-heroine

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-tale-from-old-kawhia

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-stealing-of-an-atua-god

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/maungaroa-and-some-of-its-legends

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-mokia-tarapunga

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-memory-of-maketu

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-tale-from-the-taupo-region

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-tale-of-the-taniwha-slayers

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-witch-trees-of-the-kaingaroa

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/there-were-giants-in-that-land

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-tale-from-old-rotoiti

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-lagoons-of-the-tuna-eels

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-legend-of-takitimu

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/the-white-chief-of-the-oouai-tribe

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/tane-mahuta-the-soul-of-the-forest

https://steemit.com/history/@len.george/a-tale-of-maori-magic

with thanks to son-of-satire for the banner