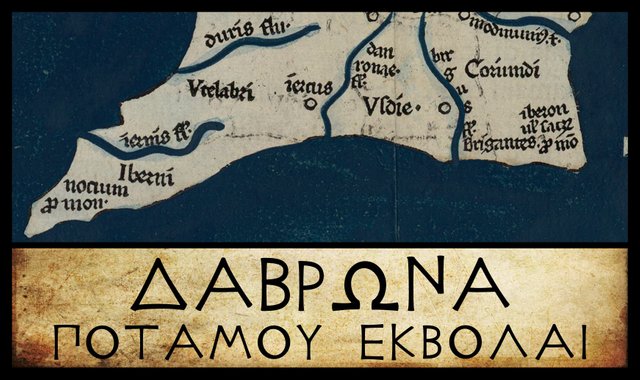

Δαβρωνα Ποταμου Εκβολαι

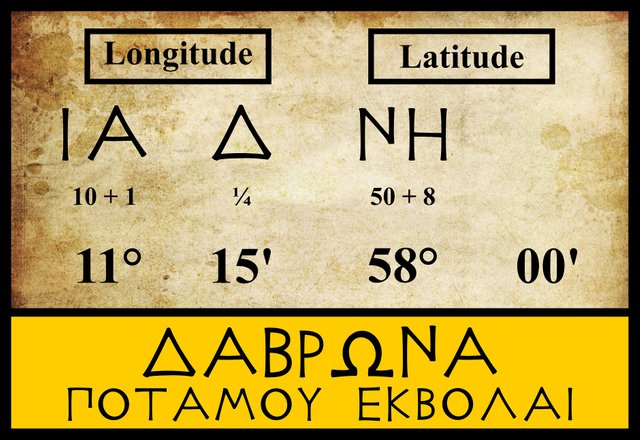

Having doubled the Southern Promontory, we are now on the final leg of our voyage around Ireland, with Claudius Ptolemy’s Geography as our sailing directions. There are just two more landmarks before we arrive back at the Sacred Promontory, the headland in the southeast corner of the island where we began this voyage. Both landmarks are river mouths, and to the first of them Ptolemy gave the name Δαβρωνα ποταμου εκβολαι [Dabrōna potamou ekbolai], or Mouth of the River Dabrōna. The three modern editors I am following locate this feature in the same latitude (57° 00') and the same longitude (11° 15'). Friedrich Wilberg records a single variant in one of the manuscript sources and one of the early printed editions, while Karl Müller notes a few other variants:

| Edition or Source | Longitude | Latitude |

|---|---|---|

| Müller, Wilberg, Nobbe | 11° 15' | 57° 00' |

| A, M | 11° 15' | 58° 00' |

| A, Σ, Φ, Ψ, 4803, 4805, [X] | 13° 00' | 58° 00' |

A is one of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, Grec 1401. Δαβρωνα appears on Folium 18. The latitude clearly has Η (eta), for the 8 in 58°. According to Müller, A has different figures for Dabrōna in its catalogue for Ireland and in its map.

M is the Editio Argentinensis, which we have met several times before. It was based on Jacopo d’Angelo’s Latin translation of Ptolemy (1406) and the work of Pico della Mirandola. Many other hands worked on it—Martin Waldseemüller, Matthias Ringmann, Jacob Eszler and Georg Übel—before it was finally published by Johann Schott in Straßburg in 1513. Argentinensis refers to Straßburg’s ancient Celtic name Argentorate.

Σ, Φ and Ψ are three manuscripts from the Laurentian Library in Florence: Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 9 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 38 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 42.

4803 and 4805 are two of the Codices Parisini Latini in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. They are Latin translations of Ptolemy’s Geography by Jacopo d’Angelo: Latin 4803 and Latin 4805.

X is Vaticanus Graecus 191, one of the oldest surviving manuscript copies of Ptolemy’s Geography. It is now housed in the Vatican Library. The River Dabrōna is on folium 139r, in the second line of text at the top of the page. Clearly, it locates the mouth of the Dabrōna in longitude 13° (ιγ ) and latitude 58° (νη), though Müller does not include it among the manuscripts that give these variant figures.

A few variant readings of this river name have been recorded. Some of these differ only in their Greek accents, which were not used in Ptolemy’s day:

| Edition or Source | Longitude | Latitude |

|---|---|---|

| Müller, Wilberg, Nobbe | Δαβρώνα | Dabróna |

| F, L, M, O, P, R, Ω, Δ | Δαβρῶνα | Dabrõna |

| ב | Οὺαβρῶνα | Oùabrõna |

| X, D | Δάβρωνα | Dábrōna |

F is Coislin 337, one of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. It is believed to date to the 14th or 15th century.

L is a manuscript from the library at Vatopedi, the ancient monastery on Mount Athos in Greece.

Ο is Oxoniensis Seldanus 2, 45, one of the Selden Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library at Oxford.

P and R are Venetian manuscripts identified by Müller as Venetus 383 and Venetus 516. They are possibly kept in the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, though I have not been able to confirm this.

Ω, is another manuscript from the Laurentian Library in Florence: Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 49.

Δ is Florentinus Abbatiae 2380, a codex from the Abbey of St Lawrence in Florence.

ב is identified by Müller as Scorialensis Ω, I, 1. This is a manuscript in one of the libraries in the royal seat of El Escorial in Spain. Its spelling of Ptolemy’s Δαβρωνα as Οὺαβρῶνα [Oùabrõna] is probably just a misreading of Delta [Δ] as Omicron [Ο]. The digraph οὺ [ou] was regularly used by Ptolemy and his contemporaries to represent the Celtic phoneme [v] or [w] (O’Rahilly 41), so Οὺαβρῶνα would be read as Vabrōna, or Wabrōna.

D is another of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, Grec 1402.

Marcian

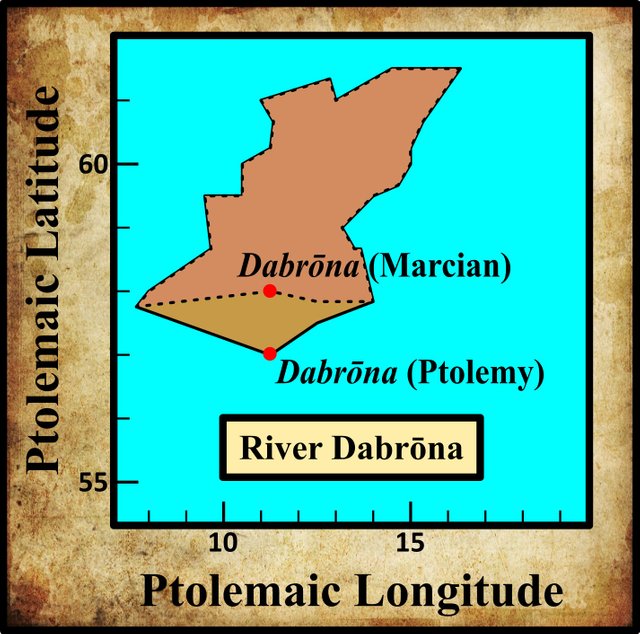

In the preceding article in this series, I mentioned another early geographer, Marcian of Heraclea, who flourished in the 4th century of the Common Era, about two hundred years after Ptolemy. In his Periplus of the Outer Sea, Marcian quotes Ireland’s dimensions as 2,170 stadia from west to east and 1,834 stadia from south to north (Miller 103-104). He measures these lengths from two of the promontories of Ireland: the Southern Promontory in the southwest and the Rhobogdian Promontory in the northeast. Goddard Orpen’s analysis of Marcian’s figures demonstrates that Marcian agreed with the commonly accepted Ptolemaic latitude for the latter of these landmarks (61° 30') but that he placed the former headland five minutes of arc further north than Ptolemy (57° 50' versus Ptolemy’s 57° 45').

Orpen believed that Marcian used these two landmarks to measure both the longitudinal and the latitudinal width of Ireland because on Marcian’s map of Ireland these headlands were not only the most easterly and westerly points on the island but also the most northerly and southerly. In most modern editions of Ptolemy, however, the mouths of the two south-coast rivers, the Dabrōna and the Birgos, are placed further south than the Southern Promontory:

Indirectly, however, the plan of measurement adopted by Marcian supplies an argument of some force bearing on the positions of the rivers Dabrona and Birgus. It is plain that Marcian had Ptolemy’s geography before him. The fact then that he measures the maximum breadth of Ireland (from south to north), by the difference of latitude between the Notium [Southern] and the Rhobogdium promontories strongly supports the correction suggested as to the position of those rivers, for if Ptolemy placed the Dabrona in lat. 57, why did not Marcian take his measurement of the greatest breadth from it? (Orpen 121)

It is, of course, possible that Marcian, or one of his predecessors, simply assumed that Ptolemy had called the southwestern headland Notion Akron, or Southern Promontory, precisely because it was the most southerly point on the island, and amended Ptolemy’s figures accordingly. It has to be said that neither version of the south coast resembles the actual south coast of Ireland. Ptolemy’s version is V-shaped, and Marcian’s is Λ-shaped, whereas the real thing is more like /¯. Marcian’s outline is, perhaps, closer to the real thing.

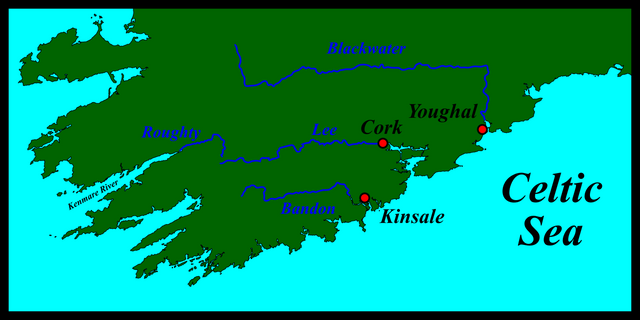

Identity

Ptolemy’s River Dabrōna is commonly identified with the River Lee, which flows through Cork City into Cork Harbour and the Celtic Sea. In the 12th century, Gerald of Wales named two rivers in County Cork, with the Latin names: Saverennus and Luvius (Dimmock 30). These are usually identified with the Bandon and the Lee respectively (Forester et al 23 fn 6), but it is more likely that they both refer to the River Lee, as T F O’Rahilly once pointed out:

An early name of the River Lee was Sabrann, identical with that of the Severn (Welsh Hafren, Lat. Sabrina). Later this was supplanted by an alternative name, which is also well attested, viz. Lua or Luae, gen. id., dat. Luí. [Footnote: Giraldus Cambrensis, hearing both names, made two rivers out of one: “Saverennus et Luvius per Corcagiam” ...] Lua, which could go back to something like *Lovia, must be closely related to, if not identical with, the rare word ló (O’Davoren) or lua (O’Clery), “water,” cognate with Lat. lavo and Greek λούω. From the dat. Luí, which came to be used as nom., we get the Mod. Ir. name of the River, Laoi, indeclinable ... We may take it, therefore, that Lua was originally a common noun, meaning “the water”, “the river”, which persisted as a local name for the Lee after it had fallen into disuse in ordinary speech, and which eventually displaced Sabrann, the proper name of the river. (O’Rahilly 1933:215-216)

Some years later, O’Rahilly elaborated on the etymology of the earlier name:

Dabrōna. Its position indicates the Lee, the old name of which was Sabrann, so that the Δ [Delta] of Ptolemy’s text is a misreading of Σ [Sigma]. Further -ωνα [-ōna] is probably to be read as -ονα [-ona_], for -onā is a common ending of Celtic river (and goddess) names, e.g. *Agronā, Dēvonā, Mātronā. With Sabronā compare Sabrinā (W[elsh] Hafren), the Severn, which differs only in the vowel of the suffix. (O’Rahilly 1946:4)

Goddard Orpen had earlier expressed a similar opinion:

Ptolemy in all probability derived his information as to Ireland directly or indirectly from merchants who traded in her ports. Tacitus expressly says of it “melius aditus portusque per commercia et negotiatores cogniti” [Its harbours and approaches are better known through trade and traders]. Now Cork Harbour is much the most important natural harbour on the south coast or indeed in the whole of Ireland, and it would be strange if Ptolemy omitted to notice it. The site of Cork city, too, must always have been an important site. The ancient name for the river Lee, which flows into Cork Harbour, was the Sabhrann (see “Four Masters,” sub anno 1163 [M1163.10]), the equivalent of the Latin Sabrina and the Welsh Hafren, and I suspect that Ptolemy’s Δαβρώνα (v.l., Οὺαβρῶνα) is a corruption of Σαβρώνα. If then the mouth of the Sabrona be Cork Harbour, and if we are justified in supposing that Ptolemy placed it in lat. 58, the town of Ἰουερνίς would occupy approximately the site of the city of Cork. (Orpen 121)

In the early 17th century, the British antiquarian William Camden did not fall into the trap of confusing Gerald’s Saverennus with the River Bandon:

Over-against Kinsale, on the other side of the river [Bandon], lies Kerry-wherry, a small territory lately belonging to the Earls of Desmond. Just before it, runs the River which Ptolemy calls Daurona, and Giraldus Cambrensis, through the change of one letter, Sauranus, and Saveranus; which, springing from the Mountains of Muskery, passes by the principal City of the County ... Giraldus calls this Corcagia; the English, Cork; and the natives Corkig. (Camden 1338)

Camden’s 18th-century editor Edmund Gibson glossed Camden’s mention of the Saveranus with the words: “being at present called Lee”. But many scholars who came after Camden made the same mistake as Gerald. Among these were the 17th-century Irish antiquarian James Ware and his 18th-century editor Walter Harris:

Daurona, a River: According to Camden, the River which runs by Cork is called Daurona, which Giraldus Cambrensis (as Camden says) calls Saverennus. Cambrensis indeed affirms, that the Saverennus and Luvius run through Cork, that is, the County so called, not the City. But the River which flows round the City of Cork is at this Time called the Lee, and, I am of Opinion, is the same with the before-mentioned Luvius. But (if I am not mistaken), the Daurona is now called the Aven-more, i. e. the great River, which falls into the Ocean near Youghall. (Ware & Harris 39)

Youghal lies further along the coast, about 40 km ENE of Cork. The River that flows through Youghal is now called the Blackwater, one of several Irish rivers with that name. It is sometimes referred to as the Munster Blackwater to distinguish it from the others.

Walter Harris only compounds Ware’s error with his gloss:

Daurona seems to be a Latin Termination given to two old British Words, i. e. Dav-Rian, or the Queen-River, and signifies much the same thing as Aven-More, or the great River. (Ware & Harris 39)

As usual, Harris has not been able to resist including a scholarly etymology culled from the pages of William Baxter’s Glossary of British Antiquities:

Daurona or Dabrona, a well-known river of Ireland. Ptolemy calls it this, while in Giraldus it is Saverenus, but ought to be written Sabriana. It is the same as our ancient Dav Rian and Sav Rian, both of which mean Queen River. Among the Irish, it is known as the Avon Mor, or Great River, meaning the same thing. (Baxter 99-100)

William Beauford, writing in 1789, also followed Baxter, but he added an etymological novelty of his own:

Δαβρῶνα. This river Camden thinks is the river Lee or Cork river, which is also the opinion of Cambrensis, who calls it Saveranus. But it was most probably the Dubh Riannagh and Abhann Mor of the Irish; now Blackwater or Youghal river. Dubh Riannagh is pronounced Duvronna, nearly. (Beauford 62)

Beauford is here connecting Ptolemy’s Dab with the Irish dubh [Old Irish: dub], meaning black. But Beauford’s Irish name for the Blackwater—Dubh Riannagh—is his own creation.

Charles Trice Martin followed Baxter and Harris, identifying both the Dabrona and the Daurona with the River Avonmore, Cork, Ireland.

Most other scholars have followed Camden and identified Ptolemy’s River Dabrōna with the Lee.

Dabrona or Labrona?

If Ptolemy’s Δαβρωνα was derived from Sabronā, the hypothesized Celtic name for the River Lee, then somewhere along the line of transmission the initial letter Σ (S) was corrupted to Δ (D). While this is certainly possible, it is not very probable. In Ptolemy’s day, these two letters were not particularly similar. On the other hand, the Greek letter Lambda, Λ (L) is very similar to Delta and the could be easily confused. So, there is a possibility that Ptolemy’s Dabrōna should be corrected to the Celtic Labronā. Now, it so happens that there was a river in the southwest of Ireland with such a name:

Labrainne ... According to an old tradition, found in Lebor Gabála [The Book of Invasions], and also in the verse Dindshenchas of Loch Éirne, three rivers “burst forth” during the reign of Fiachu Labrainne, viz. (to quote them in the genitival forms in which they occur in the texts) Fleisce, Mainne (MD, III, 462) or Mane (LL, 17 b 45), and Labrainne. In Keating’s version the rivers (aibhne) are called Innbhear Fleisce, Innbhear Mainge, and Innbhear Labhrainne (FF, II, 126). the Fleisce, nom. Flesc, is the River Flesk, which enters Loch Léin near Killarney. The Mainne (nom. Mann?) is doubtless the Maine (in later Irish an Mhaing), which flows into Castlemaine Harbour. That the Labrainne or Labrann [Footnote: Labrann may represent an earlier *Labaronā, which would be a likely name for a noisy river (cf. Labarā in Holder, II, 113, and the suffix -ōna in river-names, ib., 859).] is also in Kerry is made clear from other contexts in which the name occurs, e.g. Ériu, VI, 148, where it is mentioned in a list of Munster places (dat. Labraind, YBL; Labraindi, Lism.), and Ac. Sen. 6049, where there is mention of Inber Labarthuinde (the spelling is due to a false etymology) re hEirinn aníar In the dramatic story of Mongán summoning Caílte from the dead (that is to say, from Tech Duinn, which was located in one of the rocky islets to the south-west of Dursey Island), the initial stages of Caílte’s journey, as indicated by the rivers he has to cross, are first Labrinni (dat.), next Maín (dat.), then Lemuin (the Laune) and Loch Léin (Voyage of Bran, I, 47; and cf. ZCP, XVIII, 416). I suggest that Labrinni here must mean the sea-inlet known as the Kenmare River; while the Maín is, I think, to be identified with the Caragh River (and Lake), the only stream of any importance between the Kenmare River and the Laune ... Labrann, I take it, was the early name, not merely of the Kenmare River, but also of the River Roughty, of which the Kenmare River forms the estuary (inber). (O’Rahilly 1933:212-214)

I am not the first to make the suggestion that Ptolemy’s Δ is an error for Λ. Annie M. Heiermeier, a pupil of the Bohemian Celticist Julius Pokorny, made the same suggestion in her 1952 article “The British and Goidelic Element in Ireland”: Notes and Suggestions on T. F. O’Rahilly’s: Early Irish History and Mythology:

As suggested already by other scholars (cf. Pokorny in ZCP XXI, 127) one can more easily imagine a scribal error Δ for recte Λ, rather than for Σ, so that perhaps *Labrōna for Dabrōna would be more likely than *Sabrōna. (Heiermeier 38)

More recently, the experts at Roman Era Names have also suggested such a misreading, while, however, accepting the consensus view that Ptolemy was referring to the River Lee:

Δαβρωνα river mouth (Dabrona 2,2,6) was the river Lee past Cork and Cobh. A scribal error may have changed Λ into Δ, so that the river was originally called *Labrona. As explained here, early river names containing Lav- (or similar) do not fit the usual Gaelic explanation of ‘talkative’ nearly as well as a pan-European or Latin-influenced ‘likely to rise’. Cork is extremely vulnerable to flooding because it lies in the middle of a large and complex river catchment. (Roman Era Names)

The link leads to a PDF article on the possible etymology of Lav-. I will quote just one short paragraph from the beginning and leave the reader to consult the rest at leisure:

Almost certainly Lav- meant some kind of river, but what type of river? There are two main candidate explanations: one is a “Celtic” word for ‘talkative’ or ‘noisy’; the other is a Latin-influenced meaning of ‘intermittent’ or ‘likely to rise’.

It is the former that O’Rahilly was referring to when he described Labaronā as “a likely name for a noisy river”. If O’Rahilly’s etymology is accurate, then the possible corruption of Celtic Labaronā to Ptolemy’s Dabrōna would require more than a simple misreading of the initial letter. (O’Rahilly later suggested Labronā as the original form of the name—see quotation below.)

Another problem with this theory is the undeniable fact that every surviving manuscript of Ptolemy’s Geography places the mouth of the River Dabrōna on the south coast of Ireland, not the west coast. But this is where the plot thickens. In Ptolemy’s description of the west coast, the most southerly river he catalogues is the Iernos, which many scholars (including O’Rahilly) emend to Īvernos. As we saw in an earlier article, this river is commonly identified with the River Roughty, and also the Kenmare River, into which the Roughty flows. O’Rahilly, again, is one scholar who make this identification:

Iernos is doubtless for *Īvernos, as Iernē, ‘Ireland’, is for *Īvernē. The River Roughty, flowing into the Kenmare River, is probably intended. The old name of this in Irish was Labrann (Hermathena xxiii, 212 ff.), < *Labaronā or *Labronā. (O’Rahilly 1946:4)

Now, it just happens that in his description of the south coast of Ireland, Ptolemy includes a “city” called Ivernis and a tribe called the Iverni, both of them in the same region as his River Dabrōna:

Iverni Their name has survived as Érainn, which goes back to a variant form *Ēvernī. Ptolemy’s Iverni were situated approximately in what is now Co. Cork, just as the name Érainn is applied chiefly to the Érainn of Co. Cork. (O’Rahilly 1946:9)

Ivernis is placed by Ptolemy a little to the north-west of the mouth of the Dabrona (the Lee). The name has not survived; but the place intended is probably either Ard Nemid, situated somewhere on the Great Island in Cork Harbour, or Dún Cermna, situated on the Old Head of Kinsale. (O’Rahilly 1946:14)

Is it possible, then, that the names of the Labrona (the Roughty and|or Kenmare River) and Ivernos (the Lee) were inadvertently switched at some point? The probable alteration of Labronā to Dabrōna suggests that this part of Ptolemy’s text was subject to some corruption. The confusion over the latitudes of the mouths of the Dabrōna and Birgos also testifies to ongoing corruption. Note also that the latitude of the Ivernos as given by Ptolemy is 58°, the same as the variant reading for the latitude of the Dabrōna found in about a dozen manuscripts of the Geography.

What is most surprising about this hypothesis is that no one seems to have suggested it before.

References

- William Baxter, Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum, sive Syllabus Etymologicus Antiquitatum Veteris Britanniae atque Iberniae temporibus Romanorum, Second Edition, London (1733)

- William Beauford, Letter from Mr. William Beauford, A.B. to the Rev. George Graydon, LL.B. Secretary to the Committee of Antiquities, Royal Irish Academy, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 3, pp 51-73, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1789)

- William Camden, Britannia: Or A Chorographical Description of Great Britain and Ireland, Together with the Adjacent Islands, Second Edition, Volume 2, Edmund Gibson, London (1722)

- Robert Darcy & William Flynn, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: A Modern Decoding, Irish Geography, Volume 41, Number 1, pp 49-69, Geographical Society of Ireland, Taylor and Francis, Routledge, Abingdon (2008)

- Louis Francis (editor, translator), Ptolemy’s Geographia: Selections, English, University of Oxford Text Archive (1995)

- Thomas Forester (translator), Richard Colt Hoare (translator), Thomas Wright (editor), The Historical Works of Giraldus Cambrensis, George Bell & Sons, London (1905)

- Annie M Heiermeier, “The British and Goidelic Element in Ireland”: Notes and Suggestions on T. F. O’Rahilly’s: Early Irish History and Mythology, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 82, Number 1 , pp 37-44, Dublin, (1952)

- Charles Trice Martin, The Record Interpreter: A Collection of Abbreviations, Latin Words and Names Used in English Historical Manuscripts and Records, Reeves and Turner, London (1892)

- Emmanuel Miller, _Périple de Marcien d’Héraclée, Epitome d’Artémidore, Isidore de Charax, etc., ou, Supplément aux Dernières Éditions des Petits Géographes : D’après un Manuscrit Grec de la Bibliothèque Royale _, L’Imprimerie Royale, Paris (1839)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor and translator), Geographi Græci Minores, Volume 1, Firmin-Didot, Paris (1882)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor and translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Charles O’Conor, Dissertations on the History of Ireland to which is subjoined a Dissertation on the Irish Colonies Established in Britain with Some Remarks on Mr Mac Pherson’s Translation of Fingal and Temora, George Faulkner, Dublin (1766)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Notes on Irish Place-Names, Hermathena, Volume 23, Number 48, pp 196-220, Trinity College, Dublin (1933)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- Patrizia de Bernardo Stempel, Ptolemy’s Celtic Italy and Ireland: A Linguistic Analysis, in David N Parsons & Patrick P Sims-Williams (editors) Ptolemy: Towards a Linguistic Atlas of the Earliest Celtic Placenames of Europe, University of Wales, CMCS Publications, Aberystwyth (2000)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- The Mouth of Cork Harbour: © Paul Johnston-Knight, Creative Commons License

- The Mouth of the Blackwater at Youghal: © john berry, Creative Commons License

- The River Lee at Cork: © Francis Franklin, Creative Commons License

Very good post dear

Posted using Partiko iOS