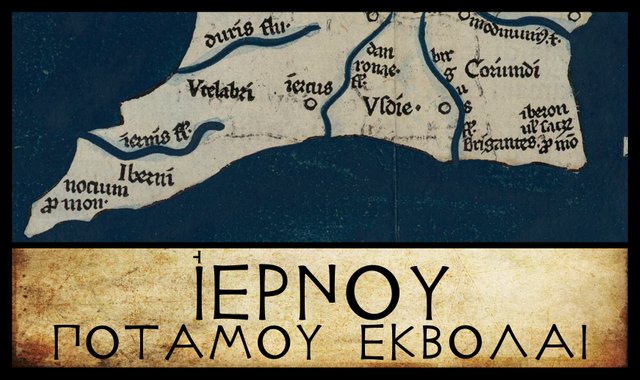

Ἰερνου Ποταμου Εκβολαι

Continuing our voyage down the west coast of Ireland, with Claudius Ptolemy’s Geography as our sailing directions, our penultimate landfall is the mouth of the River Iernos. This is another toponym whose identity is still hotly debated.

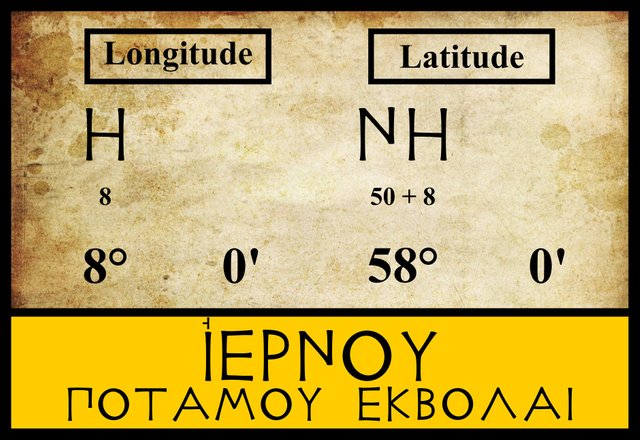

The three modern editors I am following place this feature in the same latitude (58°) and longitude (8°), and they do not record any departures from these figures in the manuscript tradition. There are, however, a few variant readings of the name of this river.

| Edition or Source | Greek or Latin | English |

|---|---|---|

| Müller, Wilberg, Nobbe | Ἰέρνου | Iernou |

| A, Z | ἰέρου | ierou |

| M | Ieri ἰεροι | Ieri ieroi |

A is one of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, Grec 1401. ἰέρου appears on Folium 18.

Z is Vaticanus Palatinus Graecus 314, a Greek manuscript from the old Palatinate Library of Heidelberg, and now part of the Vatican Library.

M is the Editio Argentinensis, which we have met several times before. It was based on Jacopo d’Angelo’s Latin translation of Ptolemy (1406) and the work of Pico della Mirandola. Many other hands worked on it—Martin Waldseemüller, Matthias Ringmann, Jacob Eszler and Georg Übel—before it was finally published by Johann Schott in Straßburg (Argentinensis refers to Straßburg’s ancient Celtic name Argentorate) in 1513.

Ptolemy recorded this feature as Ἰερνου ποταμου εκβολαι [Iernou potamou ekbolai], or mouth of the river Iernos, correctly construing the name of the river in the genitive case, and implying the nominative case Ἰερνος [Iernos]. The variant readings recorded by Müller can be dismissed for reasons which will become clear presently.

Identity

In the early 17th century, the British antiquarian William Camden attempted to identify Ptolemy’s River Iernos, but with little success and less confidence. In his description of County Desmond—“Now annex’d, part of it to Kerry and part to Cork”, as Camden’s 18th-century editor Edmund Gibson noted—he described how the west coast of this now-defunct county comprised:

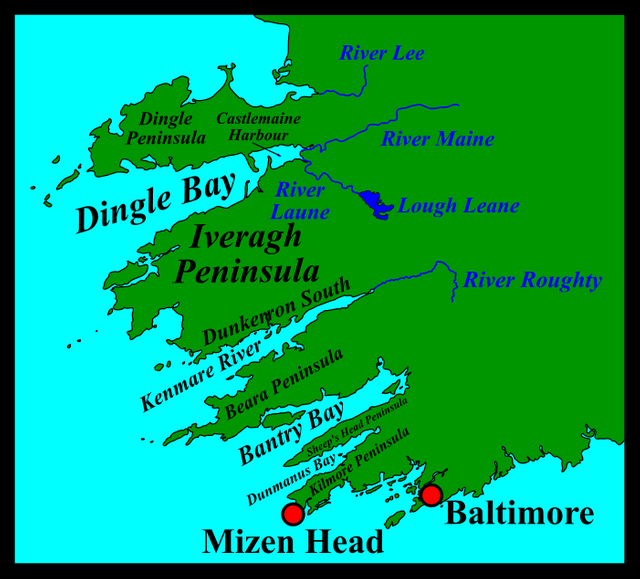

parcels of Land divided from one another by great incursions of the Sea ... Among these Arms of the Sea, are three several Promontories ... The third Promontory, named Eraugh [or Iveragh] lies between Bantre and Balatimore or Baltimore ... this is that Promontory which Ptolemy calls Notium, or the South-Promontory, and is at this day call’d Missen Head. Under this Promontory (as we may see in that Author) the river Iernus falls into the Sea. As for the present name of that river, I dare hardly pretend to guess at it; unless it be that which is now call’d Maire [or Kilmaire], and runs under Drunkeran as aforesaid. (Camden 1336)

Gibson glossed Camden’s Eraugh as Iveragh, which is probably correct, but a glance at a map will show that Camden was not actually talking about the Iveragh Peninsula, which lies further north, but to the pair of peninsulas known today as Sheep’s Head Peninsula and Kilmore Peninsula. Bantry Bay lies to the north of the former, while Baltimore lies to the south of the latter. Mizen Head lies at the end of Kilmore Peninsula. However, Camden’s River Maire is the Kenmare (or River Roughty, as it is known today), which flows into the sea between the Iveragh and Beara Peninsulas. Drunkeran is Dunkerron South, a barony on the Iveragh Peninsula. All in all, Camden’s geography of this part of Ireland is muddled and unsatisfactory, and Gibson’s comments are of little help to the confused reader.

The 17th-century Irish antiquarian James Ware agreed with Camden, identifying the Iernus with the River Kilmare, or Roughty, which flows into Kenmare Bay (or Kenmare River, as this deep inlet is also known):

Iernus, a River. The River Kilmare in the County of Kerry, where there is a noble Haven. [Some substitute Ibernus here instead of Iernus.] (Ware & Harris 40)

The bracketed comment was added by Ware’s 18th-century editor Walter Harris, a renowned antiquarian in his own right. As usual, Harris has been consulting his copy of the Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum (Glossary of British Antiquities) by the Welsh Celticist William Baxter. Baxter’s entry under the heading Iberni (a Celtic tribe mentioned by Ptolemy in his description of Ireland) includes the following:

Iberni Corrupted in some manuscripts of Ptolemy, where they are called Ὀυτερνοι [Outernoi], unless this be read as συνωνύμως [synonymous]; and just as the Ἀυτειροι above, or ancient Iberni. These were a people of Ireland, where the river Ibernus was situated, in the extremity of Munster. (Baxter 134)

It is an interesting emendation, which still has its supporters today. The Celticist T F O’Rahilly, writing in 1946, noted:

Iernos is doubtless for *Īvernos, as Iernē, ‘Ireland’, is for *Īvernē. The River Roughty, flowing into the Kenmare River, is probably intended. The old name of this in Irish was Labrann (Hermathena xxiii, 212 ff.), < *Labaronā or *Labronā (O’Rahilly 4)

I have mentioned before O’Rahilly’s theory that when the letter digamma became obsolete in ancient Greek, the Greeks had no way of representing the letter v or w in foreign place names, so they simply dropped it (O’Rahilly 41 fn 2). Later, this sound was denoted by the digraph -ου-. Ptolemy, for example, called Ireland Ἰουερνια [Ivernia]. But in the case of many less well-known toponyms, the lost letter was never restored. Ἰερνος [Iernos] was one such toponym:

Ptolemy, or some near predecessor of his, modernized Ἰέρνη into Ἰουερνία, and similarly inserted ου into the cognate names Ἰούερνοι and Ἰουερνίς, but by an oversight forgot to change the river-name Ἰερνου (gen.) into Ἰουερνου (O’Rahilly 41-42)

Īvernos, therefore, is probably the correct Celtic form of the name. The contributors to Roman Era Names also accepted this emendation, while suggesting a possible alternative:

Ιερνου river mouth (Iernu 2,2,4) should perhaps be emended into Ιουερνου (Hywernu) or Ιερον (Hieron) to fit other names in Ireland. The modern Iveragh peninsula is explained in Irish as Uibh Rathach ‘descendants of Rathach’, but that might just be reinterpretation. This river could be either the Maine into Castlemaine Harbour or the Roughty into Kenmare Bay. The latter seems marginally more likely, because it has more evidence of early habitation and is fractionally warmer (according to online climate data), as also discussed below under Ιουερνις.

Iveragh and Ivernos

The large peninsula between Dingle Bay and Kenmare Bay is called the Iveragh Peninsula. Could this toponym preserve an echo of Ptolemy’s River Ivernos? As the passage above noted, Iveragh is generally regarded as an Anglicization of the Irish Uíbh Ráthach. The first word, uíbh, is the dative plural of ó or ua, meaning grandson, grandchild or descendant. But why is the dative plural used in this place name? With reference to the similarly styled Uíbh Fhailí (Offaly), Nollaig Ó Muraille made the following comment on the website Logainm:

The Irish form in regular use for the past forty years represents a petrified dative or locative form Uíbh Fhailí—‘petrified’ is a technical term that means that the form cited does not change any more according to case. (Strictly speaking, the rather more correct form would be Uíbh Failí, since Uíbh was not usually followed by lenition.) There are other Irish place-names with a similar structure, e.g. that of the Iveragh peninsula (and barony) in south-west Co. Kerry (Uíbh Ráthach), the barony of Iveagh, Co. Down (Uíbh Eachach), the barony of Iverk, Co. Kilkenny (Uíbh Eirc), the territory of Iveleary in the barony of Muskerry in West Cork (Uíbh Laoghaire), a parish called Iveruss in Co. Limerick (Uíbh Rosa), or a townland called Evegallahoo in the same county (Uíbh Gallchú—earlier Uíbh Gallchubhair).

But Old Irish did not have a locative case, and the use of the dative case in a locative sense was rare (Thurneysen § 251.3). I suspect there is more to this story than we now know.

And what about the second word in this toponym, Ráthach? This is sometimes glossed as abounding in raths, or earthen forts. But that does not really make any sense. Irish kingdoms, territories and their ruling families usually had names like Uí Néill (Descendants of Niall of the Nine Hostages), or Uí Briain (Descendants of Brian Ború), or Uí Dúnlainge (Descendants of Dúnlaing), where the second element was the genitive case of a person’s name. So Ráthach must be the genitive case of someone’s name. The genitive singular inflexion in -ach was not uncommon in Old Irish, and is still found in modern Irish today: cathair (city), cathrach. The Old Irish personal names Cúanu and Echu had the genitive forms Cúanach and Echach (Thurneysen § 319.2(c)), so it is possible that there was an historical or mythical character called Ráthu, who was regarded as the ancestor of the family who ruled the Iveragh Peninsula in the early Middle Ages. In Old Irish, ráth could mean surety or guarantee. Hostage-taking was a common practice in ancient Ireland. It was common for a liegeman’s sons to be given to the local king as guarantees of his loyalty. Might one such hostage have been named, or nicknamed, Ráthu?

Patrick Weston Joyce did not include the toponym Iveragh in his classic study The Origin and History of Irish Names of Places, but his opinion on the subject was recorded by P J Lynch, a Fellow of the Royal Irish Academy:

The etymology of Iveragh ... is not very clear. Dr. Joyce has favoured me with his views on the Irish form as used by O’Heerin. He writes—“Ui Rathach (or O Rathach in the plural genitive) and, as in such names the dat. pl. Uibh is often substituted for the nom. Ui, the modern anglicised form Iveragh was evolved from Uibh Rathach and nearly represents its sound. In such names the part following Uibh is nearly always a personal name. The Ui is descendants, or tribe, of such and such an ancestor, but I will not venture to give a meaning to rathach—O’Daly, I remember, states that it means ‘abounding in raths’, but that is only a guess, and hence is not satisfactory.” (Lynch 42-43)

Whatever the true origin of Iveragh, the fact that Ptolemy’s Ivernos has an -n- in the middle of it, which is not the case with either Iveragh or Uíbh Ráthach suggests that there is no connection between the two.

Charles Trice Martin may not have been aware of the common emendation of Ptolemy’s Iernos to Ivernos, or perhaps he found the temptation to leave Iernos unemended and link it to River Erne irresistible. Nevertheless, he still gave a nod to the received wisdom of Camden et al:

Iernus—River Erne, or Kenmare Bay, Ireland.

As we saw in the preceding article in this series, Goddard Orpen was not willing to commit himself:

We might expect the western coast to be the least known to the Romans, and it is certainly the hardest to recognise from Ptolemy’s indications. The river Σηνος [Sēnos] is generally taken to be the Shannon ... though the Δούρ [Dour] is nearer the proper position for that river. If the Σηνος be the Shannon, then the Δούρ and the ’Ιερνος would represent two of the estuaries in Kerry and Cork. (Orpen 118)

Karl Müller, whose edition of Ptolemy’s Geography was published in 1883, included a lengthy comment on the Iernos. The only part that concerns us, however, is the following sentence:

It seems to indicate the river that discharges into Kenmare Bay, which lies to the north of Iveragh. (Müller 77)

| Kenmare or Roughty | Bantry Bay | Erne | Maine | Dingle Bay or Castlemaine Harbour |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camden (1607) | - | - | - | - |

| Ware(1654) | - | - | - | - |

| Baxter (1733) | - | - | - | - |

| - | Beauford (1789) | - | - | - |

| Martin (1892) | - | Martin | - | - |

| Orpen (1894) | Orpen | - | Orpen | Orpen |

| - | - | - | - | Quiggin (1911) |

| O’Rahilly (1946) | - | - | - | - |

| Rivet & Smith (1979) | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | Mac an Bhaird (1991-93) | - | - |

| Francis (1994) | - | - | - | - |

| Ikins (1996-2005) | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | Toner (2002) | - | - |

| Stempel (2002) | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | Darcy & Flynn (2008) | - |

Source: Darcy & Flynn 56

With the exception of the River Erne, all the candidates that have been proposed for Ptolemy’s Iernos (or Ivernos) have been either one of the large inlets in the southwest of the country or one of the rivers that flow into these inlets.

In the previous article I tentatively accepted Mary Hickson’s identification of Ptolemy’s Dour with the River Lee that flows into Tralee Bay, principally on account of the survival of the local toponym Moyderwell, which seems to preserve the name of the Dour. That leaves three significant inlets and one smaller inlet before we reach Mizen Head and the end of the west coast: Dingle Bay, Kenmare River, Bantry Bay, and Dunmanus Bay. The River Ivernos must be either one of these bays or a river that discharges into one of them. All of these rivers are short and not particularly significant, but that is also true of the Lee.

If pressed, I would opt for Kenmare River, as it is the only one of the four bays that has traditionally been regarded as a river. On the other hand, Bantry Bay is probably of more value to sailors. In the Sailing Directions for Ireland, issued by the United States Naval Oceanographic Office in 1962, we are told:

Bantry Bay, entered northward of Muntervary [Sheep’s Head], extends northeastward to the harbors at its head. A light is shown on Muntervary. The bay is easy of access, free from dangers in the fairway, and with scarely any current. A fairway between Muntervary and the southwestern end of Whiddy Island is marked by light buoys and leads to the deepwater oil terminal at Whiddy Island. The holding ground is good but the bay is exposed to westerly winds. Sheltered anchorage can be taken by the deepest draft vessels in Bear Haven off the northern shore, and in Glengarriff and Whiddy Harbors near the head of the bay. (USNOO 141-142)

Contrast this with the warnings given for those who sail into the Kenmare River:

Kenmare River, a narrow, deep inlet, is entered between Cod’s Head and Lamb’s Head about 4½ miles north-northwestward. The town of Kenmare stands at its head about 22 miles within the entrance. The bold, high land on both sides of the entrance rises to elevations in excess of 1,000 feet. The rocky and indented shores are mostly foul and must be approached with caution. The central part of the inlet is deep and clear as far northeastward as Maiden Rock (51°49' N., 9°48' W.). Above this rock the inlet narrows and is obstructed by numerous rocks, islets, and shoals. The head of the inlet dries. Small vessels can find shelter in the bays on either shore; large vessels anchor near the head of the inlet ... DANGERS OFF THE NORTHERN SIDE OF THE ENTRANCE ... DANGERS ON THE SOUTHERN SIDE OF THE ENTRANCE ... (USNOO 147-148)

Perhaps early mariners or merchants who frequented these waters—whether Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans or Celts—would have recorded the safer harbours in preference to the more dangerous ones.

References

- William Baxter, Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum, sive Syllabus Etymologicus Antiquitatum Veteris Britanniae atque Iberniae temporibus Romanorum, Second Edition, London (1733)

- William Beauford, Letter from Mr. William Beauford, A.B. to the Rev. George Graydon, LL.B. Secretary to the Committee of Antiquities, Royal Irish Academy, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 3, pp 51-73, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1789)

- William Camden, Britannia: Or A Chorographical Description of Great Britain and Ireland, Together with the Adjacent Islands, Second Edition, Volume 2, Edmund Gibson, London (1722)

- Robert Darcy & William Flynn, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: A Modern Decoding, Irish Geography, Volume 41, Number 1, pp 49-69, Geographical Society of Ireland, Taylor and Francis, Routledge, Abingdon (2008)

- Louis Francis, Geographia: Selections, English, University of Oxford Text Archive (1995)

- P J Lynch, Some of the Antiquities Around St. Finan’s Bay, County Kerry, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 32 (Consecutive Series), Volume 12 (Fifth Series), Ponsonby & Gibbs, Dublin (1902)

- Charles Trice Martin, The Record Interpreter: A Collection of Abbreviations, Latin Words and Names Used in English Historical Manuscripts and Records, Reeves and Turner, London (1892)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Notes on Irish Place-Names, Hermathena, Volume 23, Number 48, pp 196-220, Trinity College, Dublin (1933)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- E C Quiggin, Ireland: Early History, in Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 14, pp 756-770, New York (1911)

- Albert Lionel Frederick Rivet, Colin Smith, Place-Names of Roman Britain, B T Batsford, London (1979)

- Patrizia de Bernardo Stempel, Ptolemy’s Celtic Italy and Ireland: A Linguistic Analysis, in David N Parsons & Patrick P Sims-Williams (editors) Ptolemy: Towards a Linguistic Atlas of the Earliest Celtic Placenames of Europe, University of Wales, CMCS Publications, Aberystwyth (2000)

- Gregory Toner, Identifying Ptolemy’s Irish Places and Tribes, in David N Parsons & Patrick P Sims-Williams (editors) Ptolemy: Towards a Linguistic Atlas of the Earliest Celtic Placenames of Europe, University of Wales, CMCS Publications, Aberystwyth (2000)

- USNOO, Sailing Directions for Ireland, H O Pub 30, United States Government Printing Office, Washington (1962)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- Kenmare River: © Richard Wilton, Creative Commons License

River Roughty (10 km Upstream from Kenmare): © Jonathan Billinger, Creative Commons License - Bantry Bay from Sheep’s Head Peninsula: © Trevor Rickard, Creative Commons License

- Dunmanus Bay (Looking Towards Mizen Head and Sheep’s Head Peninsula): © Jonathan Billinger, Creative Commons License

- River Roughty with Kenmare Bridge: © Ron Goodhew, Creative Commons License

Very useful historical post.

Very informative post it was

Hi harlotscurse,

Visit curiesteem.com or join the Curie Discord community to learn more.

Quite a long history. I love the view of that Kenmare river (the first one), i really haven't heard on if before now...😃 it looks so serent there...