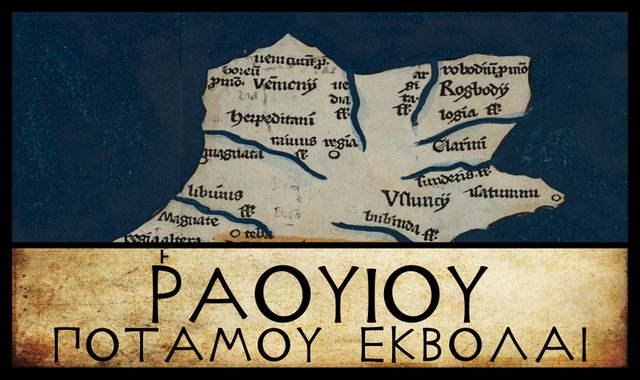

‘Ραουιου Ποταμου Εκβολαι

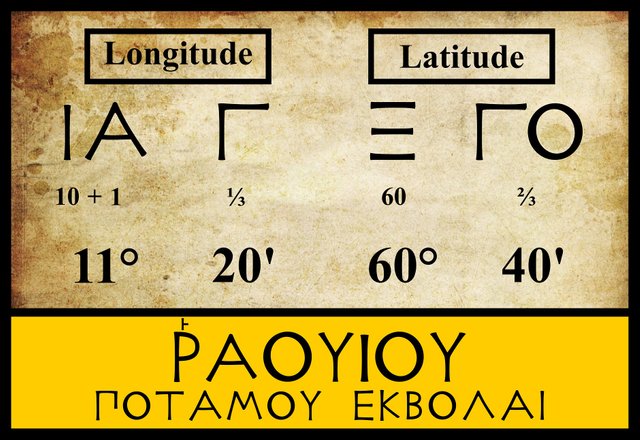

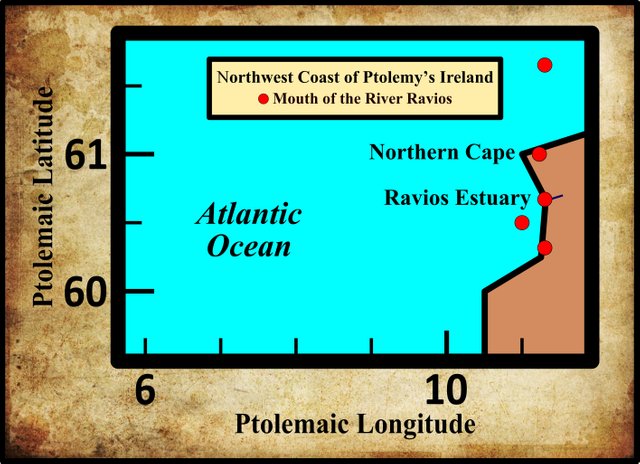

Having doubled the cape of Bloody Foreland in the northwest corner of Ireland, we continue our circumnavigation of the island by proceeding down the west coast, with Claudius Ptolemy’s map as our guide. The first landfall we make is the mouth of another river, to which Ptolemy gives the name Ravios. Little agreement has been reached as to the identity of this river, and even its position has been fluid over the centuries. The three modern editors I am following assign the same coordinates to this feature, but at least four variant locations are recorded in earlier sources:

| Edition or Source | Longitude | Latitude |

|---|---|---|

| Müller | 11° 20' | 60° 40' |

| Wilberg | 11° 20' | 60° 40' |

| Nobbe | 11° 20' | 60° 40' |

| Ψ | 11° 15' | 61° 00' |

| Σ, Φ, M | 11° 20' | 60° 20' |

| L | 11° 20' | 61° 40' |

| D, A | 11° 00' | 60° 30' |

Σ, Φ and Ψ are three manuscripts from the Laurentian Library in Florence: Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 9 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 38 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 42.

M is the Editio Argentinensis, which we have met several times before. It was based on Jacopo d’Angelo’s Latin translation of Ptolemy (1406) and the work of Pico della Mirandola. Many other hands worked on it—Martin Waldseemüller, Matthias Ringmann, Jacob Eszler and Georg Übel—before it was finally published by Johann Schott in Straßburg in 1513.

L is a manuscript in the library at Vatopedi, the ancient monastery on Mount Athos in Greece.

D and A are two of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, Grec 1402 and Grec 1401 respectively.

The only variant reading noted by the modern editions is ’Αουιος (Avios), in which the initial rho has been lost. This is found, for example, in one of the manuscripts of Ptolemy’s Geography from the Bibliotheca Palatina (Palatinate Library) of Heidelberg, which is now in the Vatican Library. It is safe to dismiss this as a transmissional error.

We have already come across Ptolemy’s use of the Greek digraph -ου- to represent the -w- or -v- sound of foreign languages. In Ptolemy’s day there was no longer any letter in the Greek alphabet to represent this sound. The digamma, ϛ, which had once fulfilled this role, was only used by Ptolemy to represent the numeral 6 and the fraction ⅙.

As usual, Ptolemy records this masculine river name in the genitive case, governed by εκβολαι, “river mouth”. ‘Ραουιος (Ravios) is the nominative form. The only other thing to note about Ptolemy’s orthography of ‘Ραουιος is the rough breathing. In ancient Greek, an initial rho, Ρ, always took the rough breathing:

13. Every initial ρ has the rough breathing:_ ῥήτωρ orator_ (Lat. rhetor). Medial ρρ is written ῤῥ in some texts: Πυῤῥος Pyrrhus.

14. The sign for the rough breathing is derived from Η, which in the Old Attic alphabet ... was used to denote h. Thus, ΗΟ ὁ the. After Η was used to denote η, one half (ⱶ) was used for h (about 300 B.C.), and, later, the other half (˧) for the smooth breathing. From ⱶ and ˧ come the forms ‘ and ’. (Smyth 10)

So Ptolemy’s ‘Ραουιος can be transliterated as both Rhavios and Ravios. The latter is believed to be a better representation of how this name would have been pronounced in ancient Ireland, so this is the form I prefer to use.

Identity

The identity of the River Ravios has not yet been established with any degree of certainty, though this is not for a lack of plausible candidates. In the early 17th century, the English antiquary William Camden set a trend by identifying it with the River Erne. The second-longest river in Ulster, the Erne rises in County Cavan and flows through several lakes, including Upper and Lower Lough Erne, before entering the sea at Ballyshannon in County Donegal:

Higher up, the County of Slego (very proper for grazing,) lies full upon the Sea; bounded on the North by the River Trobis, which Ptolemy calls Ravius, and which springs from the Lough Ern in Ulster. (Camden 1385)

Today, County Sligo is separated from the Erne by County Leitrim, but in the 17th century, the Erne did indeed form part of Sligo’s northern boundary. Camden’s name for the Erne, the Trobis, anticipates John Speed’s map of 1611-12, where the Erne is called the Trowis. This appears to be a corruption of Drowes, the name of a much smaller river that flows from Lough Melvin parallel to the Erne and enters the sea about 5 km south of the estuary of the Erne.

Half a century after Camden, the Irish antiquary James Ware endorsed Camden’s identification but also corrected his error:

Ravius, a River: The River Ern, or that Part of it which rising out of Lough-Earn passes through a Part of the County Donegall. It is called by Giraldus Cambrensis, Samarius, and by Camden, Mercator, and Spencer, erroneously, Trowis. (Ware & Harris 43)

Edmund Spenser included the “Sad Trowis, that once his people over-ran” in a catalogue of Irish rivers at the wedding of the Thames and Medway in his epic poem The Faerie Queene (4:11:41) : significantly, the Erne does not appear among the wedding guests. When Spenser described the Trowis as overrunning his people, he was probably alluding to an origin-myth that Lough Erne burst forth from dry ground, drowning the local inhabitants for their sinfulness (Camden 1396).

In Gerardus Mercator’s Atlas Sive Cosmographicae Meditationes de Fabrica Mundi et Fabricati Figura, the Erne is erroneously called the Trowys. Spenser worked on Book 4 of The Faerie Queene around 1590-96, while Mercator’s atlas was published posthumously by his son Rumold in 1595. I suspect that the error preceded both men, though I cannot hazard a guess as to who originated it. Presumably someone, looking at a map in which the name Trowis was written above the river Drowes—and, therefore, just below the nearby Erne—mistakenly took the name as referring to the Erne, and their error was repeated by others.

Over the centuries, the Erne has been the most popular choice for Ptolemy’s Ravios. In his history of Ireland, Ogygia, which was first published in Latin in 1685 and in English translation in 1793, Roderic O’Flaherty wrote:

Ravius is corruptly written for the river Samar, that runs from Loch Erne. (O’Flaherty & Hely 25)

The Samar, or, in Latin, Samarius, derives from an old Irish name for the river: Samair, or Samhaoir. which possibly means tranquil (cp sámhaireacht, tranquillity). The etymology, however, is obscure:

It is to be observed that Samer was in former times used also as a woman’s name; but what the radical meaning of the word may be, I cannot venture to conjecture. As a river name, Pictet (Origines Indo-Europiennes [150]) connects it with the old names of several rivers on the continent of Europe, and with the Persian shamar, a river : — for example the Samur, flowing from the Caucasus into the Caspian; the Samara, flowing into the Sea of Azov; and the ancient Celtic name, Samara, of a river in Belgium. (Joyce 486)

Assaroe

Writing in 1892, Charles Trice Martin also identified the Ravios with the Erne, though he referred to the latter as a river in Connaught. Two years later Goddard Orpen not only identified Ptolemy’s Ravios with the Erne but also provided some interesting linguistic evidence to back up the claim:

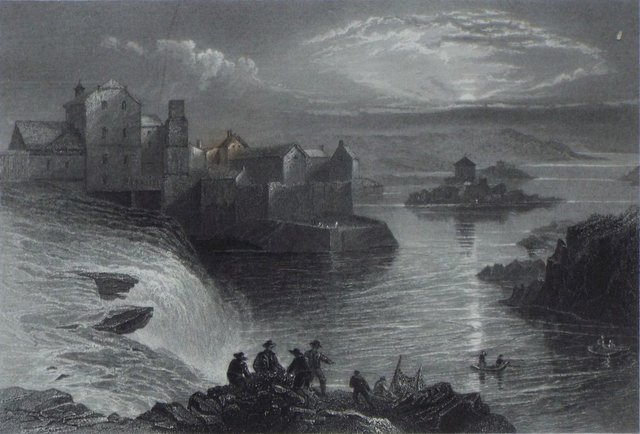

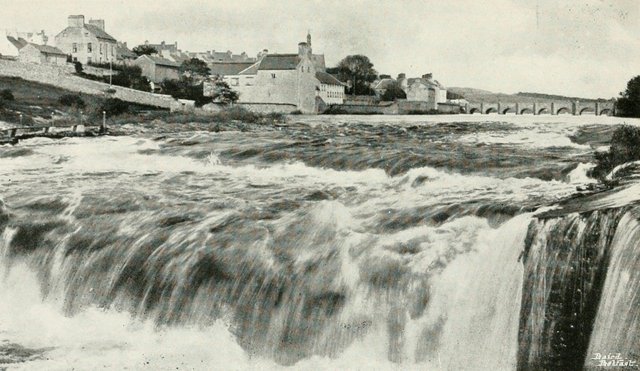

Lastly, the ‘Ραουιος would be somewhere in Donegal Bay, probably the Erne, also called the Samhair, and known at the cataract at Ballyshannon as Eas Ruaidh. Indeed, it is just possible, as Prof. Rhys has suggested to me, that Ruaidh was originally some proper name more nearly Ruai, which might have been fairly represented by ‘Ραουιος. “The appending of the dh, after those letters had become silent, in this position, would be easily done by the scribes, and having got so far as Ruaidh this looked like an epithet, and so an Aedh Ruadh was posited, and the place came to be called Eas Aedha Ruaidh, the cataract of Hugh the Red.”—“Four Masters,” A.M. 4518; “Ogygia,” iii. 36. It is noteworthy that the form Eas Ruadh, or Eas Ruaidh, is more frequent than the form Eas Aedha Ruaidh; and, in fact, an alternative traditionary derivation from a woman’s name “Ruad” (Lat. rufa) is given in the Book of Ballymote. (See passage quoted in “Silva Gadelica,” Translation, pp. 479, 526.) (Orpen 118)

Before commenting on this passage, we should also read what T F O’Rahilly had to say on the etymology of these toponyms:

Ravios would seem to correspond geographically to the River Erne, flowing into Donegal Bay. We have the same name (except for a change of gender and declension) in Roa, the River Roe, Co. Derry, which would go back to *Raviā ... Ravios may mean ‘roarer’ or the like, and be cognate with Lat. răvus, ‘hoarse’. Its Irish equivalent is probably seen in Roae (older *Rauë?), the name of one of ‘the two historians of the Táin’, the other being Ro-án ... Ravios would regularly give O. Ir. disyllabic Raue (Roa, Roe), gen. Raui, later monosyllabic Rua, gen. Ruí (Roí) (O’Rahilly 5 ... 454)

Although O’Rahilly is known to have used Goddard Orpen as a source (O’Rahilly 1, fn 2), it is curious that he has nothing to say about Orpen’s suggestion that Ravios may be linguistically connected with Eas Ruaidh, the Irish name of the now-extinct waterfall (or salmon-leap) at Ballyshannon, known in English as Assaroe. Elsewhere, O’Rahilly does refer to the Falls of Assaroe, glossing Ess Ruaid as ‘Ruad’s waterfall’, named for the mythical Aed Ruad, who was drowned in the waterfall (O’Rahilly 319-320). Obviously, the presence of the -d- in Ess Ruaid argues against a derivation from Ptolemy’s Ravios, but as the Celticist John Rhys suggested, it is possible that Ruaid is a later corruption.

As we have seen, O’Rahilly noted that Ravios is essentially the masculine equivalent of the original name of the River Roe in Derry. This led him to suspect that the latter was in fact the river Ptolemy was referring to:

As it is perhaps unlikely that there should have been two rivers of this name, one in the north-west and the other in the north of Ireland, it is quite possible that Ptolemy’s names may have become disarranged at this point, and that the River Roe may be the river referred to by Ptolemy. (O’Rahilly 5)

Is it really unlikely that there should have been two rivers called the Roe? Today, there are no less than seven rivers in Ireland called the Blackwater. In fact, the old name for the Erne itself, Samhaoir, was also the name of another river in Limerick (since corrupted to Camhaoir, the Morning Star River). O’Rahilly’s view, however, has been endorsed by F J Byrne and M J O’Kelly in Volume 9 of A New History of Ireland, and by Seán Duffy in his Atlas of Irish History.

Karl Müller

In his 1883 edition of Ptolemy, Karl Müller broke new ground, as far as I know, when he offered the following identification for the Ravios:

The River Ravios, insofar as it is placed about 200 stadia from the Northern Promontory (Bloody Foreland), can be seen to be the river which discharges at Trawenagh Bay. (Müller 76)

Müller can only be referring to the Owenamarve River, which has its mouth on Trawenagh Bay on the west coast of Donegal. This is not a particularly long river, and one that is not well known outside its immediate vicinity. It rises as the Owenmacroo River near Crocklaunaght in the Derryveagh Mountains, and flows through a series of small lakes before reaching the sea. As the crow flies, the distance between source and outlet is little more than 10 km. It is hardly credible that Ptolemy would have included such an insignificant stream in his Geography.

Next door to the mouth of the Owenamarve is that of the better-known and much longer Gweebarra River. In Ptolemy’s day, 200 stadia was about 37 km (Cuntz 111), which would actually bring us south of Gweebarra Bay. Did Müller simply misread his map and mistake Trawenagh Bay for Gweebarra Bay?

Recent Candidates

Since 1990, three other rivers have been thrown into the mix:

- Srahmore River, which flows into Clew Bay in County Mayo.

- Newport River, which also flows into Clew Bay in County Mayo.

- Roughty River, which flows into Kenmare Bay in County Kerry.

None of these is particular significant—I’ve never heard of the first two, myself. The Irish name of the Roughty, Ruachtach, bears some superficial similarity to Ravios, but it is probably not related. O’Rahilly believed that the Irish name was recent and derived from the name of the valley through which the river flows. Its location, in the far south-west of the country, does not accord with Ptolemy’s list.

The Srahmore and the Newport were both proposed by participants of a 1999 workshop at the University of Wales in Aberystwyth, whose papers appeared in the collection: Ptolemy: Towards a Linguistic Atlas of the Earliest Celtic Placenames of Europe. Curiously, neither of these rivers has a name that is linguistically similar to Ptolemy’s. Srahmore is the Irish Srath Mór, which means “Great River Valley” (Dinneen 1110), while the Newport is known in Irish as Abhainn Uaithne, which means “Owney’s River”, Uaithne being a male personal name (Dinneen 1285). I have not read the two papers in which these identifications were made, so I do not know how the authors arrived at their conclusions. At face value, it is hard to take them seriously.

A candidate of a different sort has been recently proposed by the etymologists at Roman Era Names:

Ραουιου river mouth (Rawiu 2,2,4) was Donegal Bay. Rav- is a difficult name element, which Italian scholars explain with “pre-Latin” *rava- ‘cliff landslide’ in Ravello, and possibly Ravenna. For the early names in Britain Ardua ravenatone, Ravatonium, and Αβραουαννου [Abravannou] we also discuss words for ‘river’, ‘grey-yellow’, and ‘raven (sea bird)’. All these explanations tend to point towards the high sea cliffs of Slieve League near the mouth of the Bay, rather than the river Erne flowing through Ballyshannon into the Bay.

The sea cliffs at Slieve League are among the highest in Europe, and if Ravios were identified as a promontory, they would certainly be strong candidates. But all extant sources of Ptolemy’s Geography identify Ravios as a river mouth.

| Erne | Roe | Owenamarve | Srahmore | Newport | Roughty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camden (1607) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ware (1654) | - | - | - | - | - |

| O’Flaherty (1793) | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | Müller (1883) | - | - | - |

| Martin (1892) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Orpen (1894) | - | - | - | - | - |

| O’Rahilly (1946) | O’Rahilly | - | - | - | - |

| - | Byrne & O’Kelly (1984) | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | Mac an Bháird (1991-93) |

| Francis (1994) | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | Duffy (2000) | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | Parsons & Sims-Williams (2002) | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | Stempel (2002) | - |

| Darcy & Flynn (2008) | - | - | - | - | - |

Source: Darcy & Flynn 56

In my opinion, the obvious choice for the Ravios is the River Erne. It is the first significant river south of Bloody Foreland, and I would be surprised if it were omitted from Ptolemy’s Geography. The fact that Ptolemy’s name for the river can be connected—possibly—with the Irish name for the Falls of Assaroe near the Erne’s outlet at Ballyshannon also favours this identification.

References

- William Camden, Britannia: Or A Chorographical Description of Great Britain and Ireland, Together with the Adjacent Islands, Second Edition, Volume 2, Edmund Gibson, London (1722)

- Otto Cuntz, Die Geographie des Ptolemaeus: Galliae, Germania, Raetia, Noricum, Pannoniae, Illyricum, Italia, Weidmann, Berlin (1923)

- Robert Darcy & William Flynn, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: A Modern Decoding, Irish Geography, Volume 41, Number 1, pp 49-69, Geographical Society of Ireland, Taylor and Francis, Routledge, Abingdon (2008)

- Patrick S Dinneen, An Irish-English Dictionary, New Edition, Irish Texts Society, Dublin (1927)

- Seán Duffy, Atlas of Irish History, Third Edition, Gill and MacMillan, Dublin (2011)

- Patrick Weston Joyce, The Origin and History of Irish Names of Places, Volume 2, M H Gill & Son, Dublin (1883)

- Charles Trice Martin, The Record Interpreter: A Collection of Abbreviations, Latin Words and Names Used in English Historical Manuscripts and Records, Reeves and Turner, London (1892)

- T W Moody, F X Martin, F J Byrne (editors), A New History of Ireland, Volume 9, Maps, Genealogies, Lists: A Companion to Irish History, Part II, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1989)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Roderic O’Flaherty, James Hely (translator), Ogygia, Or, A Chronological Account of Irish Events, Volume 1, W McKenzie, Dublin (1793)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- David N Parsons, Patrick Sims-Williams (editors), Ptolemy: Towards a Linguistic Atlas of the Earliest

Celtic Place-Names of Europe, CMCS Publications, University of Wales, Aberystwyth (2000) - Adolphe Pictet, Les Origines Indo-Européenes, ou, Les Aryas Primitifs, Première Partie, Joël Cherbuliez, Geneva (1859)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- Herbert Weir Smyth, A Greek Grammar for Colleges, American Book Company, New York (1920)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- Donegal and Sligo from the ISS: Wikimedia Commons, NASA, Chris Hadfield (photographer), Public Domain

- Falls of Assaroe: William Henry Bartlett (artist), J T Willimore (engraver), George Virtue, London, Public Domain

- Salmon Leap of Assaroe, Ballyshannon (1908): Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

- Trawenagh Bay: © Mac McCarron (photographer), Creative Commons License

- River Roughty: © Ron Goodhew, Creative Commons License

- Newport River: © Bob Shires, Creative Commons License

- Burrishoole Channel, Outlet of the Srahmore River: © Colin Park, Creative Commons License

- Slieve League, County Donegal: Wikimedia Commons, Thorsten Pohl (photographer), Public Domain

- The Mouth of the River Erne: © Louise Price, Creative Commons License

- The River Erne at Belleek: © David Dixon, Creative Commons License

Great history dear @harlotscurse

Resteemed and Upvote

Spectacular story friend I loved congratulations that good that you are back with us your work is great greetings

Wow! such a wonderful history and very nice article. Thank you for share this post.

Great history .good article .thanks for share .dear @harlotscurse

Love to read ur post

How r u buddy