Some further rough and loose notes on Pyrrho or Pyrrhonian skepticism in modern times (Updated version)

Introduction

My previous loose notes post did not do justice to the Pyrrhonian philosophical “position”. In the time since, I have read in more detail, figuring out the more complex “whats”, “hows” and “whys”. Here are just some “rough” loose notes on Pyrrhonism, rectifying my previous post and going into more detail. Pyrrhonism is in a sense a journey, so enjoy the ride. (See Notes below for the quotes, they are rather lengthy but are really interesting.)

The following should be read as the inquiry into the nature of a good life. There are a staggering and confusing amount of accounts of how to live a good life, from self-help books to popping pills. This exposition should not be read as an inquiry into the nature of truth or gaining truth. One can read it like this, but I am not making this argument in any epistemological way. Please look up “Pyrrhonian Reflections on Knowledge and Justification” by Robert Fogelin for a purely epistemological account.

tl;dr: Holding dogmatic beliefs = anxiety because of the fear of losing said dogma = suspension of judgement (after the sceptic’s inquiry) = ataraxia, freedom of anxiety = by-product of inquiry = because no dogma to defend = ongoing inquiry = good because not assenting to something you don’t know (which in our current society is sometimes a problem, i.e. aisles on aisles of self-help books, everyone claiming to know how to lead a good life) = suspension of judgement.

1. Honey is sweet vs. Honey appears to be sweet

Person x has a belief that honey is sweet. When this belief is not met, unease (disgust, etc.) is felt. Why? A certain “expectation” of how the world “should” be is not met, i.e. person x’s belief that is sweet. When you take away that belief, that honey is sweet, and replace it with honey appears to be sweet, the unease will (theoretically) be taken away when this belief is not met. Why? Because there is no belief about how the world “should” be, only appearances of how the world appears to be. (See quote (1) below where Pyrrho uses this especially about ethical or moral claims.) The aim then for the Pyrrhonist is to not have this unease which he/she associates with holding beliefs.

2. Holding beliefs

Sextus, who wrote about 200-400 years after Pyrrho on Pyrrhonism states the following:

“[Pyrrhonists] do not hold beliefs in the sense in which some say that belief is assent to some unclear object of investigation in the sciences, for Pyrrhonists do not assent to anything unclear,” (see the full quote (2)).

For those who hold the opinion that things are good or bad by nature are perpetually troubled. ... But those who make no determination about what is good and bad by nature neither avoid nor pursue anything with intensity; and hence they are tranquil,” (see the full quote (3)).

Two initial statements can be made: (i) the Pyrrhonist investigates things before any judgement is made (see epoché below), and (ii) the reason for this is because when trying to defend a belief or claim one will never find ataraxia because of the constant unease (anxiety) from potential loss or attack from others.

One can rightfully ask the following question: is this in itself not something unclear the Pyrrhonist assents to? Is the Pyrrhonist’s position not dogmatic? More on this below.

3. Dogma

The “goal” of the Pyrrhonist to “heal” those who suffer from holding “dogmatic beliefs”. Simply put, this is “assenting to something one cannot know”, i.e. the nature of something, e.g. if honey really is sweet. Why would you want to “heal” dogmatic beliefs? As mentioned above, holding a dogmatic belief will only lead to unease (suffering, anxiety, etc.). The Pyrrhonist wants to get rid of this unease, i.e. dogmatic belief. A dogmatic belief can be seen as for example a piece of gold. If a society believes gold is valuable, people will want to possess gold, people with golf will fear losing it, people who do not have wealth will constantly “battle” to try and possess gold. The Pyrrhonist will say get rid of the dogmatic belief that gold is good (or bad) and you will find ataraxia, freedom from anxiety. (One can see how this puts the Pyrrhonist in a dogmatic position.)

4. The “method”

There is no method that the Pyrrhonist follows to reach ataraxia. The above explanation may seem dogmatic, but this should hopefully get clearer along the way. Sextus says at the start of Outlines of Pyrrhonism: “By way of preface let us say that on none of the matters to be discussed do we affirm that things certainly are just as we say they are: rather, we report descriptively on each item according to how it appears to us at the time,” (PH 1.4). The following method is thus just a report, it is not something you can follow dogmatically. It is only how things appear. The reported “method”, or a “lifestyle”, is as follows:

(i) The inquirer (or skeptikoi, i.e. sceptic) is on “an epistemic journey” searching for the truth.

(ii) But on this search, the inquirer stumbles upon certain anomalies (aporia) before a “conversion” into scepticism (Vogt 2011: 36, 37).

(iii) The Pyrrhonist will set out these anomalies or oppositions, come to the realisation that all negation and affirmation are of equipollence (isostheneia), or equal weight. The Pyrrhonist will say “no more this than that” (ou mallon). (Sextus tells a story of the “conversion” into scepticism, see (4) below). The Pyrrhonist is thus not born but “made” (diCarlo 2009: 53).

(iv) Before or at the same time as one comes to realise the (noncommittal) equipollence (isostheneia) of arguments for things, suspension of judgment (epoché) follows. This is not done to all things at once, but only to things one has researched. It is also important to note that with epoché, the Pyrrhonist suspends judgement about the discovery of truth, and not truth in itself (Alican 2017: 20).

(v) Our cause of suffering (pathe) comes from holding beliefs (Thorsrud 2003: 230). Suspension of these beliefs will ensure “psychological health” (Berry 2011: 14). This is because once you hold something as the truth, you will fear losing it. Further, the Pyrrhonist, who finds out that there are “equal weight to arguments from both sides”, cannot help but suspend judgement. The Pyrrhonist will thus say nothing about the nature of things (aphasia).

(vi) This will result in the freedom from anxiety (ataraxia) but also a life without suffering (apatheia).

(vii) Pyrrhonism is a way of life; it is a practical philosophy or lifestyle (agoge) not confined to a set of rules that can be followed to the letter (Frede 1987: 179). The above exposition should also only be seen as a report of the findings that the Pyrrhonist made by taking this epistemic journey (PH I.4). It should not be followed dogmatically.

5. The “method” in one sentence

On the journey in finding truth (be it the good life, etc.) one finds stumbling blocks, preventing you to find the truth, you search for arguments but only find that every argument for and against is of equal weight, thus you suspend judgement, but one keeps on searching, inquiring and experiencing ataraxia as a by-product of this inquiry.

6. Why is this important (especially today)?

The analogy of knowledge goes as follow: knowledge is like a balloon, what we know is the inside, what we don’t know is the outside. When the volume increases, so does the surface area, i.e. the more we know, the more we don’t know as well. (Or with gaining knowledge we only realise that there is still a lot of things we don’t know or don’t have adequate knowledge about.) Why make this analogy? What does this have to do with Pyrrhonism? My reasoning is that Pyrrhonism is a humbling position to hold. It makes you suspend judgement on something you don’t really know. But one can ask, why is this important?

The one answer is, according to Sextus, that when you reach the stage where “knowledge” is reached, you will stop inquiring. When inquiry is stopped, one falls into dogma. (Side note: This in a way seems to be falsification as put fort by Popper, maybe?) When you hold dogmatic beliefs, ataraxia cannot be reached. A second answer is that the way one does this inquiry seems to be beneficial in our current fractured state. Sextus says: “Scepticism is an ability to set out oppositions among things which appear and are thought of in any way at all, an ability by which, because of the equipollence in the opposed objects and accounts, we come first to suspension of judgement and afterwards to tranquillity,” (PH I.8). This ability to set out arguments, seems to me, to be lacking in our current society. Little, or none, are taught how to argue for both sides of a topic. Carneades, for example, gave two lectures in Rome in which on the first day he defended justice and on the second day argued that it is a “form of folly” (Allen 2011).

To set out arguments (for and against) also opens your worldview, it broadens your perspective and it helps you be more accommodating (but armed with knowledge). This is a humble position which is needed to have a dialogue. When you cannot hear (or understand) what the other is saying in your dialogue, there will only be hatred and missed chances for peaceful dialogue.

7. But is this a position one wants to take?

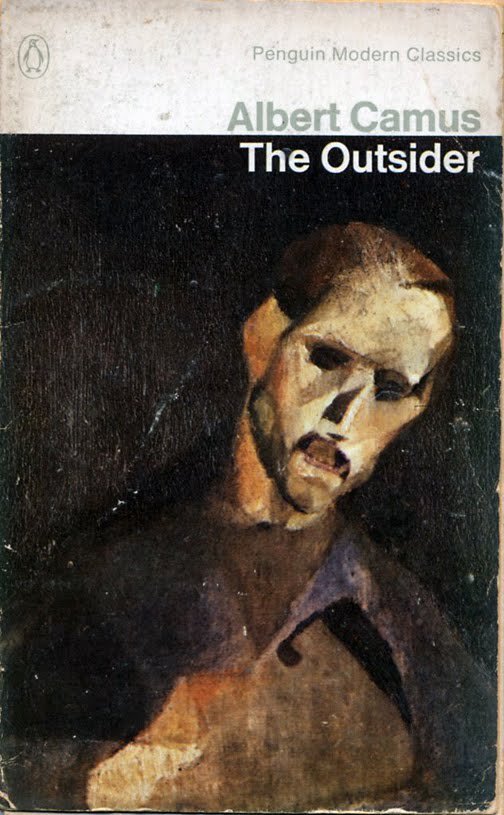

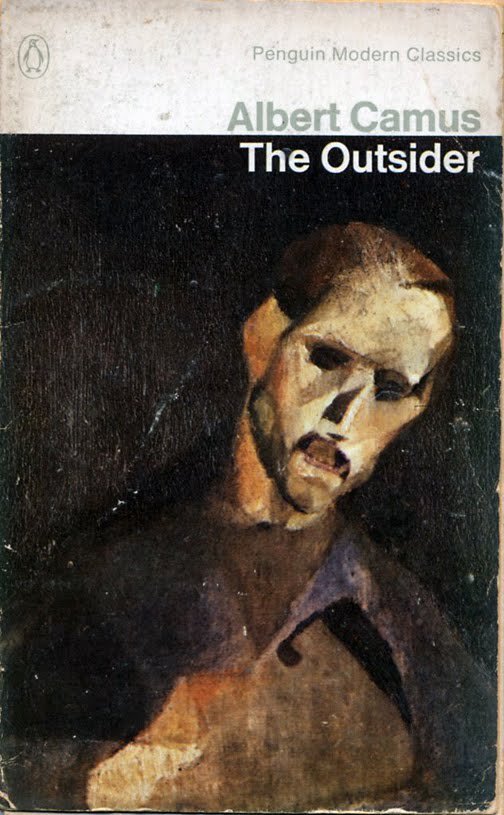

Hankinson (1995: 267-268) says the following of holding this position: “[T]here could never be a sceptical Gandhi or Martin Luther King: such lives require passionate commitment. The modern model of the sceptical way of life is Meursault in Camus’ [The Stranger]; I postpone for the moment the question of which pattern may be preferable, either psychologically or morally.”

Other argue it is psychological impossible to hold this position, that the Pyrrhonian cannot live his scepticism. Some people also make the claim that one cannot live without dogmatic beliefs (think about religious people who lose their faith but still believes in something else, for e.g. atheism etc.).

It seems too good to be true. It seems like too hard of work, to inquire everything only to suspend judgement and only to never find ataraxia. That is a question you should answer for yourself. If you read Camus’ The Outside, you will know the life Meursault lived, not the most enviable life if you can say that.

Is it better to believe in a soft lie or hard truth? I suspend judgement.

(Side note: Contemporary understanding of Scepticism is not the same as ancient scepticism, further maybe this is also a good argument to hold certain kinds of agnosticism.)

Notes/Quotes

(1) Beckwith’s (2015: 22-23) translation: “‘Whoever wants to live well (eudaimonia) must consider these three questions: First, how are pragmata (ethical matters, affairs, topics) by nature? Secondly, what attitude should we adopt towards them? Thirdly, what will be the outcome for those who have this attitude?’ Pyrrho's answer is that ‘As for pragmata they are all adiaphora (undifferentiated by a logical differentia), astathmēta (unstable, unbalanced, not measurable), and anepikrita (unjudged, unfixed, undecidable). Therefore, neither our sense-perceptions nor our doxai (views, theories, beliefs) tell us the truth or lie; so we certainly should not rely on them. Rather, we should be adoxastoi (without views), aklineis (uninclined toward this side or that), and akradantoi (unwavering in our refusal to choose), saying about every single one that it no more is than it is not or it both is and is not or it neither is nor is not,’”.

(2) PH (Outlines of Pyrrhonism) I.13, I.14: “When we say that Sceptics do not hold beliefs, we do not take 'belief' in the sense in which some say, quite generally, that belief is acquiescing in something; for Sceptics assent to the feelings forced upon them by appearances — for example, they would not say, when heated or chilled, 'I think I am not heated (or: chilled)'. Rather, we say that they do not hold beliefs in the sense in which some say that belief is assent to some unclear object of investigation in the sciences, for Pyrrhonists do not assent to anything unclear. […] But the main point is this: in uttering these phrases they say what is apparent to themselves and report their own feelings without holding opinions, affirming nothing about external objects,” (emphasis mine).

(3) PH I.27-28: “For those who hold the opinion that things are good or bad by nature are perpetually troubled. When they lack what they believe to be good, they take themselves to be persecuted by natural evils and they pursue what (so they think) is good. And when they have acquired these things, they experience more troubles; for they are elated beyond reason and measure, and in fear of change they do anything so as not to lose what they believe to be good. But those who make no determination about what is good and bad by nature neither avoid nor pursue anything with intensity; and hence they are tranquil,” (emphasis mine).

(4) PH I.28-29: “A story told of the painter Apelles applies to the Sceptics. They say that he was painting a horse and wanted to represent in his picture the lather on the horse’s mouth; but he was so unsuccessful that he gave up, took the sponge on which he had been wiping off the colours from his brush, and flung it at the picture. And when it hit the picture, it produced a representation of the horse’s lather. Now the Sceptics were hoping to acquire tranquillity by deciding the anomalies in what appears and is thought of, and being unable to do this they suspended judgement. But when they suspended judgement, tranquillity followed as it were fortuitously, as a shadow follows a body”

Sources/Further reading

Alican, N.F. 2017. No more this than that: Skeptical impression or Pyrrhonian dogma?. ΣΧΟΛΗ, 11(1): 7-60.

Allen, J. 2011. Carneades. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy [Online]. Zalta, E. N. (red.). Available: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/carneades/ [Accessed on 06 August 2018].

Beckwith, C. 2015. Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press.

Berry, J.N. 2011. Nietzsche and the ancient skeptical tradition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

diCarlo, C. 2009. The roots of skepticism: Why ancient ideas still apply today. Skeptical Inquirer, 33(3): 51-55.

Frede, M. 1987. Essays in ancient philosophy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Hankinson, R.J. 1995. The Sceptics: The arguments of the philosophers. London: Routledge.

Thorsrud, H. 2003. Is the examined life worth living? A Pyrrhonian alternative. Apeiron: A Journal for Ancient Philosophy and Science, 36(3): 229-249.

Vogt, K.M. 2011. The Aims of skeptical investigation, in D.E. Machuca (ed.). Pyrrhonism in ancient, modern, and contemporary philosophy. London: Springer. 33-50.

Images

- Still Life with Cod by Willem Roelofs

- Jesus on the Cross by Bartolome Esteban Murillo

- The Third of May 1808 by Francisco Goya

- Outsider cover art

- Pyrrho in Thomas Stanley History of Philosophy

- Unknown

*Edit: Replaced first image.

Hello @fermentedphil, thank you for sharing this creative work! We just stopped by to say that you've been upvoted by the @creativecrypto magazine. The Creative Crypto is all about art on the blockchain and learning from creatives like you. Looking forward to crossing paths again soon. Steem on!

Congratulations @fermentedphil! You have received a personal award!

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard: