What Trump should be told about the Democrat-media plot behind Watergate

PRESIDENT TRUMP says that he is being attacked unfairly by the media, who want to turn the “Russian Collusion” panic into a modern-day Watergate. Anyone who thinks the media wouldn't love to bring down Trump simply hasn't got their head screwed on straight. And the same goes for anyone who thinks that the Democratic Party wouldn't lend a hand.

A fortnight ago, right-wing news site The Federalist caught the New York Times (and just about every other media outlet) in a real whopper that could have seriously damaged Trump. You might have to read the Federalist piece twice, so slippery were the media's evasions.

The 45th President is so universally loathed by Democratic-favouring media controllers that a Pulitzer Prize is only their secondary goal at best.

And since Watergate is the standard the media are obsessing over, it is only fair that the dirty background scandal of the Washington Post's conduct during that affair is revealed -- at last.

Nixon's Watergate tip-off

RECENTLY, FOIA non-profit MuckRock.com published a piece about an alarm bell sounded by the FBI before the Watergate scandal was even a cloud on the horizon.

In June 1971 FBI Director J Edgar Hoover (pictured left) warned Republican President Nixon that there was a conspiracy against him, being planned between the media, an ex-FBI officer, and Nixon's potential challengers in the 1972 presidential election. The aim (said Hoover) was to put Democratic Senator Edward Kennedy in the White House.

MuckRock scoffs at the idea, noting that Hoover got his information from unreliable informants. This Steemit post will show how Hoover's sources may have got most of the details wrong, but what they were telling him was basically correct. There was a conspiracy, and its core participants were Senator Edward M Kennedy (younger brother of the murdered John F Kennedy), a senior FBI official called Mark Felt ("Deep Throat"), and the senior executives and owner of the Washington Post.

Whitewash at the Washington Post

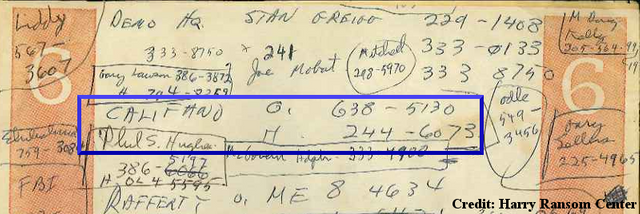

Above: Joe Califano's telephone numbers in Woodward's contacts list

ACCORDING TO All the President's Men, the Watergate book by famed reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, this is how they learned of the 17 June 1972 burglary at the Watergate complex that would eventually topple Nixon in 1974:

The first details of the story had been telephoned from inside the Watergate at 2.30am by Alfred E Lewis, a veteran of 35 years of police reporting for the Post.

However, that was a lie. The real source was the Post's chief legal advisor, Joe Califano. Califano had served as special assistant to Democratic President Lyndon Johnson until the commencement of the Republican Nixon presidency in January 1969. In June 1972, Califano also happened to be the chief legal advisor to the Democratic Party. In other words, the Post was tipped off by the Democrats and Califano was just the middle-man.

The Post plotters didn't get their stories straight, and the damning detail about Califano slipped out, unnoticed, in the 1995 autobiography of Post editor Ben Bradlee.

Woodstein (as Woodward and Bernstein were jointly nicknamed) wrote Califano out of their story. But anyone can see for themselves that Califano obviously went on to become a major source. Califano's office (“O”) and home (“H”) telephone numbers are prominent in Bob Woodward's utterly shambolic “contacts list” for his Watergate reporting (detail pictured above).

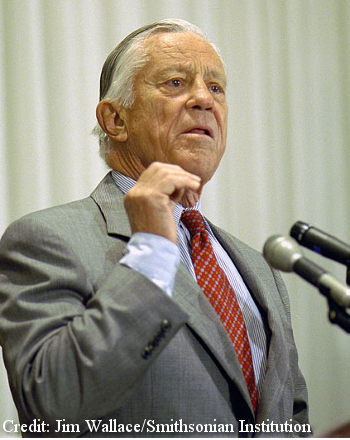

The Post's version of Watergate was compromised from the very start. Today, Bob Woodward (pictured above left) is an associate editor of the Post. He did not respond to a request for comment.

The Suppressed Kennedy Sex Scandal

Above: Darkness descends on the Watergate complex in Washington DC

CALIFANO'S SECRET ROLE was far from the only thing Woodstein airbrushed from the Watergate story. Among their very earliest leads was the fact that semi-detached CIA spook E Howard Hunt (working for the White House) had borrowed a book about Senator Edward M Kennedy from the White House library.

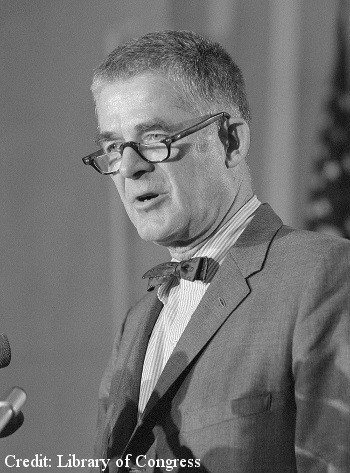

Post executive editor Ben Bradlee told the pair that the story was insufficient. In vain, Woodward argued that a reliable White House source had told them Hunt was investigating Edward Kennedy. Bradlee (pictured in 2002, left) told the reporters: “Get some harder information next time.” Hunt's library loan was never mentioned by the Post.

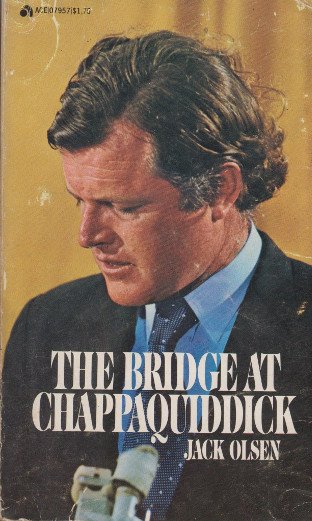

This was a great pity, because Hunt was out to smear Kennedy and it was a big story. The book Hunt was so keen to read was The Bridge at Chappaquiddick by Jack Olsen (1970). Olsen was a respected investigative author, winning multiple awards for his exposés. He had been described as “the dean of true crime” by the Post itself. Clearly, E Howard Hunt took Olsen seriously too.

Olsen's book (pictured below right) is a reinvestigation of the 1969 “Chappaquiddick Incident,” in which a young Kennedy staffer called Mary Jo Kopechne drowned in a submerged automobile after Kennedy drove off the edge of a Massachusetts bridge in the dark. That was – and still is -- the official version. Olsen's book demonstrates irrefutably that the official version cannot have been true, and puts forward another interpretation.

In Olsen's reading of events, Kennedy (who was married) and Kopechne were canoodling in the car under cover of darkness on a private road, when they spotted a police car approaching. Mindful of the potential for a career-ending scandal, Kennedy slipped out and hid in roadside bushes. Kopechne was to drive ahead without him and they would meet up again later.

Like Kennedy, Kopechne had been drinking, but was considerably smaller than Kennedy, and had never driven his heavy Oldsmobile before.

When she arrived at the bridge across Chappaquiddick's harbour – little more than a long and narrow boardwalk with no lighting or guard-rails -- she simply misjudged her speed and orientation and drove off the side, into the harbour waters.

Effectively, in “spiking” Woodstein's story about Hunt's reading material, Post editor Ben Bradlee was protecting Edward Kennedy from renewed front-page publicity about the terrible scandal that Kennedy had tried to so hard to put behind him. But Bradlee now knew that a CIA man working privately for Nixon was out to destroy a famous presidential hopeful by resurrecting that scandal. Why would a newspaper man even think of squashing a story this big?

The Burglars from the Bay of Pigs

Above: The Washington Post's offices and (inset) owner, Katharine Graham

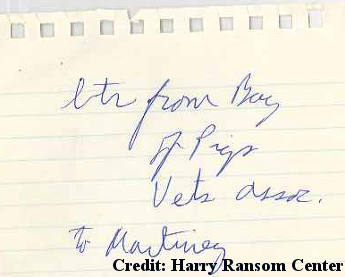

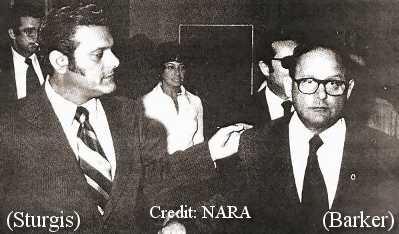

CHAPPAQUIDDICK wasn't the only connection between the Watergate affair and the Kennedy dynasty. The first had in fact come to light at the first step of the way. It can be seen on page four of Woodward's notes (pictured right), which records the discovery among the possessions of the Watergate burglars a letter “from Bay of Pigs vet[eran]s assoc[iation].”

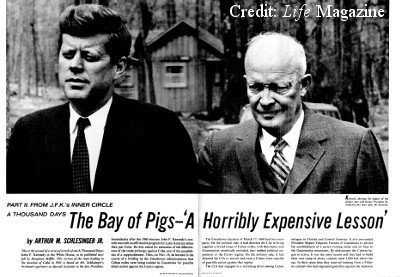

As is well-known, the Bay of Pigs was the USA's disastrous attempt to invade Cuba in April 1961, widely viewed by the CIA (the invasion's prime sponsors) as a betrayal by then-President John Kennedy. The CIA had presumed Kennedy would provide air support if the amphibious landing stalled. As it turned out, Kennedy was unwilling to risk a proxy war with Cuban leader Fidel Castro's backers, the USSR.

Yet Woodstein's book All the President's Men contains precisely one paragraph and a footnote concerning the Cuban connections of the Watergate burglars. The reporters dismiss the Bay of Pigs dimension as a “wild goose chase” that was being promoted by White House figures. This is particularly noteworthy since Woodstein's original coverage of the Watergate affair in the Post had identified the Cuba/Bay of Pigs connection on day one. For some reason, the Bay of Pigs debacle had been airbrushed from the Woodstein mythology by the time they published their book in 1974.

Fretting in the White House, Nixon regarded the prospect of a 1972 Kennedy run with foreboding. It touched a raw nerve dating from the election of 1963. (pictured left).

As the 1972 campaign season loomed on the horizon, recalled Nixon aide Charles Colson, “It was like we were running against the ghost of Jack Kennedy.”

Post editor Ben Bradlee and Post proprietor Katharine Graham were both personal associates of the Kennedy clan. This would have predisposed them to swerving anything that looked like it might damage the White House prospects of the last surviving Kennedy brother. Hence the immediate rejection of a 1972 Watergate story that threatened to revive the Chappaquiddick scandal, and the eventual 'airbrushing' of the Bay of Pigs connection from Woodstein's book.

As it turned out, the dithering Edward Kennedy decided not to run in 1972 after all, preferring instead to let the window of opportunity close in silence. Throughout that summer, polls showed Kennedy and Nixon were "neck and neck" in terms of public approval, but Kennedy said nothing. He preferred to work away from the glare of publicity -- for very sound reasons.

Kennedy's role in Nixon's downfall

Above: Kennedy (1932-2009) in later life, perhaps brooding over regrets

IN HIS 1996 BOOK Nixon and Kennedy, Christopher J Matthews describes how Edward Kennedy played the hand the Post had dealt him:

“Thanks to his position of respect on the Senate Judiciary Committee, Kennedy had the opportunity to be Nixon's most relentless prosecutor. It was a role that Jack Kennedy's brother seized with relish. Before election day in 1972 he was setting the charges that would explode the Nixon presidency.”

The autobiography of Post editor Ben Bradlee (1921-2014) is dotted with gossipy details of meetings and discussions with Kennedy on various subjects and over extended periods. Evidently, Bradlee was quite proud of their friendship. But when it comes to Watergate, it appears (from Bradlee's silence on the matter) that the Senator leading the Congressional inquiry never spoke to the close and long-term friend of his who was overseeing the journalistic inquiry.

How credible is this? By anyone's standards, the answer has to be: “It isn't.” The closest Post proprietor Katharine Graham (1917-2001) got to a public discussion of this “hidden wiring” behind Watergate was the following roll-call in her 1998 autobiography:

“Woodward and Bernstein were critical figures in seeing that the truth [of Nixon's criminality] was eventually told, but others were at least as important: Judge Sirica; Senator Sam Ervin and the Senate Watergate Commitee; Special Prosecutors Cox and Jaworski; the House Impeachment Committee under Representative Peter Rodino. The Post was an important part – but only a part – of the Watergate story.”

That paragraph is notable for the things it doesn't mention. Senator Sam Ervin, an old friend of Kennedy's, was appointed to the Senate Watergate Commitee in order (says Christopher Matthews) to “allay the suspicion that the Watergate matter was being pushed hardest by Kennedy, which, in fact, it was.” (Emphasis supplied)

“Special prosecutor Cox” was Archibald Cox, an old friend of (and Solicitor-General to) the late President Kennedy. Cox (pictured right) was appointed the first special prosecutor in the Watergate scandal because Edward Kennedy made a deal in return, not to use his Justice Committee position to block Nixon's pick for Attorney-General. Once safely in position, Cox stuffed his team of 11 with seven former Justice Department appointees from the John F Kennedy administration.

Katharine Graham's accolades point directly to Edward Kennedy and the Kennedy dynasty itself, without ever mentioning that famous surname. This is probably as near as anyone involved ever came to outright admitting Edward Kennedy's involvement in the Watergate scandal.Adam Clymer's 1999 biography of Edward Kennedy covers these tightly-knotted connections with the broad statement that “Although Kennedy's prominence kept him out of a direct role in the [Congressional] Watergate investigation, he remained involved at the edges.” But that is such an understatement that it verges on untruth.

The energy that Senator Kennedy put into overthrowing Nixon can be gauged by the fact that (according to Clymer) on 21 October 1973 Kennedy set his Senatorial staff to work on “researching how the Senate would conduct a trial if the House voted to impeach Nixon, information he turned over to the Rules Committee the next summer when the House seemed ready.” That particular October day was a Sunday, in fact the day after Nixon's infamous “Saturday Night Massacre.” Kennedy was working overtime, fixing his sights on Nixon's downfall.

Nixon (close-up pictured above) has often been dismissed as paranoid about plots against him, emanating from the Kennedy family. This is unfair. Nixon may have been paranoid, but the last surviving Kennedy brother really was out to get him. On the White House tape of 28 February 1973, Nixon can be heard telling an aide: "Yeah, I guess the Kennedy crowd is just laying in the bushes waiting to make their move. Boy, it's a shocking thing. "

All Rights Reserved, June 11, 2018

⦿ Part 2 of this story was published 2pm (EST), Weds June 13, 2018.