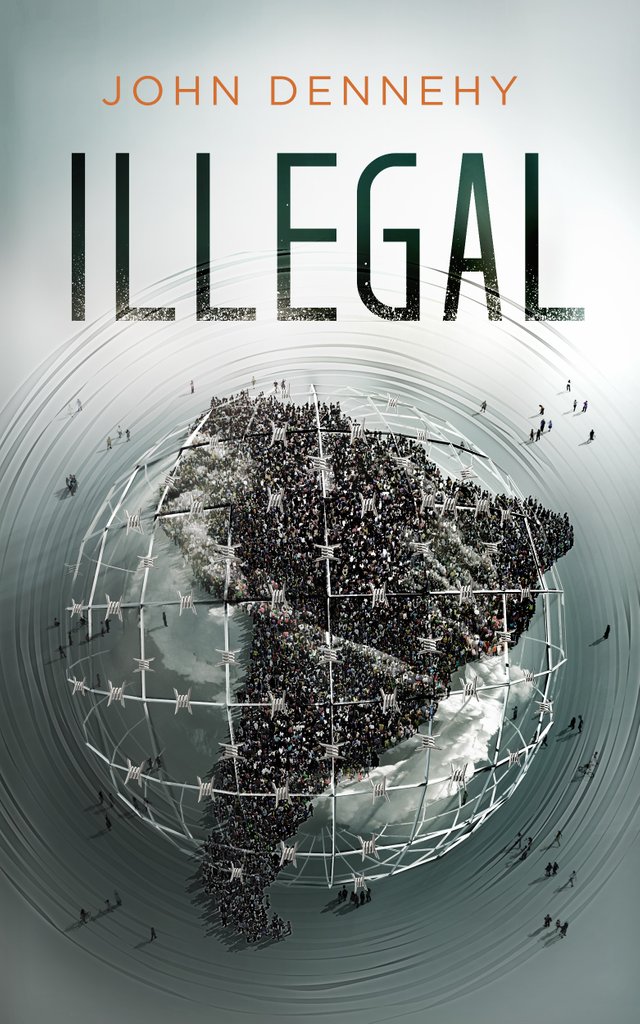

Illegal: a true story of love, revolution and crossing borders [book serialization/ Ch.3]

I'm a journalist for publications such as The Guardian, Vice, The Diplomat and Narratively and my first book, a memoir, came out just over a year ago [Amazon link]. It's won numerous awards and sold thousands of copies. And now I want to give it away. This is the second installment [Prologue | Ch 1 | Ch 2] and every few days I'll give away another chapter/ section. From the back cover:

A raw account of a young American abroad grasping for meaning, this pulsating story of violent protests, illegal border crossings and loss of innocence raises questions about the futility of borders and the irresistible power of nationalism.

In The Shadow of a Volcano [Chapter Three]

The vice president took over, the free trade deal was postponed, the blockades were lifted, and life began to seem more normal. All the notices and newspaper articles that had been tacked to the cork board in the teacher’s lounge had been taken down. In their place was a sign-up sheet to help a U.S. government-sponsored development program in a nearby mountain village. Spots were filling up fast but there wasn’t a lot of information about what was happening. I asked Steve, the first teacher who had gone, what it was like.

Steve told me he taught a few English classes and the villagers were also learning how to make pizza and hamburgers.

I learned more about the project from others. The small agricultural village was at the end of a road and didn’t have a strong connection with Cuenca nor any tourism. The project was designed to make the village more attractive to tourists to generate more income.

It wasn’t for me. I had no intention of trying to shape Ecuador into something more familiar. It also seemed a form of cultural imperialism, though I was the only one I knew of at the school who thought that.

Despite having such different reactions to the protests and foreign influence, I fell into a routine of socializing with other teachers and expats. We may have had different opinions on revolution and development, but we still had a lot in common. We were all still ‘other’ in a foreign land. People treated us differently.

It’s easy to notice when you are treated worse than others, but it can be difficult to recognize when people treat you better. It can be even harder to admit it—that your good fortune is not only due to hard work but also a privilege you did nothing to earn. In Cuenca, most foreigners were treated better than locals, myself included. Not everyone treated us better, but many did, whether it was a woman who caught your eye in a bar, or a shop owner who assumed that your underpayment was a mistake, or an employer who hired you based on how you looked. I never thought about it then. It was only much later, when nationalism washed over Ecuador and people started to treat me less favorably that I noticed. Still, even if it was to our collective advantage, being treated differently helped push all of us together. It made us all relate to each other.

As my first ninety days in Ecuador approached I had to plan a trip across the border to renew my visa. I asked around and it seemed most of the other foreigners circumventing official visa policy went to a Máncora, a Peruvian beach and popular tourist destination. I went to Tumbes instead. The two cities were in the same corner of northern Peru but I thought it’d be nice to get out of the expat bubble, if only temporarily.

Crossing back over was easy. I handed over my passport and got a stamp with another ninety days. In a way, I was still conforming to the regime of borders. Real defiance would have been throwing away my passport, but that seemed like it would cause much more trouble than it was worth. I actually didn’t think about borders much at all. I wanted my first decision in a new chapter of my life to be symbolic of my hypothetical ideal, but the theory of borders faded to the background after that.

Once I returned there wasn’t much time left. I had only committed to the school in Cuenca for a ten-week semester and once that ended I decided to do some traveling.

Latacunga was a small mountain city of 51,000 people seven hours north of Cuenca. It was just a dot on my map on the way to Quito and when I asked others about it most people gave me a version of the answer, “No one goes there to visit. It’s just a town, not a place for tourism.” And that sold me on seeing it for myself.

I arrived late at night and went straight to sleep in the first hostel I saw. In the morning I walked to the roof to try to get a view of the place. As soon as I stepped out I saw it: Cotopaxi, the world’s tallest active volcano, was just a few miles northeast of the city. Later I would learn that the summit was almost always covered in clouds, but that morning the snow-capped peak stood in sharp contrast against the blue sky.

Cotopaxi is thrice the height of the mile-high city of Denver at 19,347 feet (5,897 meters) but it wasn’t just tall; it was massive. The summit was covered with over one thousand feet of glacial ice that had built up since the last major eruption in 1877.

The city lived and died with the volcano. Glacial ice melt poured down the mountain and formed Río Cutuchi, which split Latacunga in half and provided a constant supply of fresh water. Past eruptions also filled the area’s soil with nutrients and the volcano itself trapped clouds in its orbit creating a micro-climate with plenty of moisture. Cotopaxi helped make the region ideal for different types of agriculture, from roses to potatoes to a special kind of tomato that grew on a tree. Latacunga was in the center of it all and acted as a commercial trading hub.

But Cotopaxi also destroyed the city. There might be a break of a hundred years or more between eruptions, but when Cotopaxi did erupt it was devastating. Thrice in recorded history—in 1744, 1768 and 1877— major lava eruptions melted the volcano’s glacial ice cap. The flash flood mixed with volcanic ash and gravel to form a sort of tidal wave of wet cement that followed the small valley carved by Río Cutuchi and leveled everything in its path, including most of Latacunga, just 15 miles away. Each time, the city was rebuilt.

We were a short drive away from the center of the earth—the equator—but the air was brisk on the rooftop that morning. The tropical latitude was nearly canceled out by the high elevation and gave the place a sense of permanent spring. Spring has always been my favorite season.

I walked outside the hotel and into a bustling market. Broccoli and carrots were spread across rows of tables, buckets were filled with garlic and potatoes, and bananas and mangos were piled in giant pyramids of tropical fruit trucked in from the coast. Behind each pile of produce was a woman with calloused hands, long black hair, and rosy cheeks. Other women meandered through the crowd, calling out whatever they had: “¡Diez aguacates, un dólar! ¡Diez aguacates, un dólar!” All of it smelled like my parents’ vegetable garden after a late summer rain.

When I bought my plane ticket to Ecuador I didn’t think much about the indigenous culture. It wasn’t something that ever came up. There was barely a mention of South America in all my cumulative years of history class and I had no idea how vibrant indigenous culture was in the Andes. They had largely held onto a culture and language that existed before the Europeans came, back to when they were part of the Incan empire. While nearly everyone had converted to Catholicism it was a different breed from what I was used to, mixed with their previous belief system that had worshiped nature. Quechua, the Andean indigenous language, was widely spoken in Latacunga and many of its words were mixed into the local Spanish dialect as well. In fact, the city’s name was a fusion of Quechua and Spanish. The indigenous called the original settlement ‘tacunga’ and the Spanish added the article ‘la’ when they arrived, and they eventually merged into one word. ‘Cotopaxi’ is a Quechua word which means ‘throat of fire.’ The name ‘Andes’ came from the Quecha word anti, which means ‘where the sun rises.’

In Cuenca I had learned that the countryside was majority indigenous, but Latacunga was the first city I saw with such a strong indigenous presence. Perhaps that was it though; Latacunga didn’t feel like a city, it felt like a village. It felt like a clean break from the life I left behind in New York.

I wandered farther from the market through the narrow cobblestone streets. Storefronts were not always in a uniform line and occasionally they cut into the sidewalk, making the pedestrian path so thin that you had to step into the street when someone came from the other direction. It was clearly a town built before cars. After a few minutes, I stumbled upon Parque Vincente Leon and sat down. Like the central park in Cuenca, this one was sandwiched between government buildings and a church but the buildings were far less impressive here. “¡Fuera Oxy! Fuera TLC!—No Oxy [A U.S. oil company]! No Free Trade Agreement!” was spray-painted on the Federal building’s façade. Both buildings had patches of new paint that didn’t quite match the base color—half-hearted attempts of erasing past graffiti. Vincente Leon was also much more open than its Cuenca counterpart. There were a few small trees but most of the park was covered in sun rather than shade. The buildings blocked many of the surrounding mountains, but a few of the taller peaks could be seen reaching above the rooftops.

I already liked Latacunga, so when I sat down in Vincente Leon, I was probably just looking for an excuse to stay longer. That’s when I made my first friend. Veronica had long brown hair, and while her lips shined with gloss and her eyes hid behind too much blue powder, she wore a plain green shirt and her backpack looked worn. Two years later our friendship would come to an abrupt and bitter end, but regardless, she played an oversized role in my life in Latacunga by making small introductions that would have large consequences. I was writing in my notebook when she sat down. She looked forward and kept silent, but a minute later when I paused my writing and looked up, she spoke.

“Hola.”

She smiled at me. She knew a few words of English and we struggled patiently to converse in a mix of our languages.

“What do you do?” she asked.

Two young boys, each carrying a small wooden box and a hard- bristled brush, stopped a few feet in front of us and stared.

“I’m an English teacher,” I said.

The two boys walked away, following a businessman as he walked by and asking if he wanted his shoes shined.

“Oh, really? Why don’t you come work at my university? It’s one of the best in the country,” Veronica said.

“I don’t think I’m qualified for that.”

She looked confused, and I wondered if she just didn’t understand my English. “You can work there. It’s close, I can take you there now. Why not?”

I smiled at Veronica’s question. Ecuador had infused me with the sense that anything was possible. I repeated her last words, though not loud enough for Veronica to hear. “Why not?”

The university was on a busy street and only a few blocks south of the park. The building itself had a fresh coat of white paint. Stone steps lead to massive mahogany doors that served as the main entrance. On either side were stained glass windows. Directly above the doors the two-story building rose steeply upward toward a point. The tower was much higher than the rest of the building, or any building in the neighborhood in fact. It reminded me of a cathedral. Veronica knew her way and led me down the long, stone-tiled hallway, to a row of offices.

“We are here,” she said and walked inside one of the offices.

I followed her in.

“Perdón, tengo un amigo estado unidense aquí. Él es profesor de íngles y està interesado en trabajar aquí. ¿Puede hablar con la directora?” Veronica’s words came out too fast for me to catch them all but the three or four people working in the office all looked up, then looked at me. One man smiled and stood up.

“Hello! Very nice to meet you.” He came over and shook my hand while speaking near-perfect English. “I’ll be right back with the Director. Please take a seat.”

Veronica smiled and grabbed my notebook from my hand. She wrote down her phone number on the first page. “We meet soon,” she said before kissing me on the check and walking away.

I barely had time to sit down before the Director came in. She was tall and was wearing a navy-blue pant suit. “You are interested in working here? Come, follow me.”

I stood up and followed her to a desk and two chairs in the far corner of the room.

The interview was short. Within an hour of meeting Veronica in the park I was offered a job. Ecuador was a whirlwind of adventure. I felt like a twig that had fallen into a surging river. The current twisted and turned and I let it carry me onward, enjoying all the views along the way.

“We’ll take care of everything for you here. Just come on the first day of the semester and we’ll give you housing and you’ll be able to eat in the cafeteria as well—all paid for.”

And like that, half a year after I finished an undergraduate degree in media studies and sociology I had become a college professor at one of the nation’s most prestigious universities—in a field in which I barely had any experience in and in a nation whose language I still couldn’t speak.

I had a few days before classes started so I continued my trip and revisited Quito before returning to Latacunga for the start of the new semester. When I arrived for my first day of work, two men in army fatigues took my duffel bag out of my hand.

I must have looked confused.

Another English teacher who I had seen during my interview but to whom I had not been formally introduced smiled at me. “Don’t worry; just go with them for now.”

The military men walked off with my bag.

“But … What? What are they doing?”

“Go! Go! They’ll bring you back here in a minute. Don’t worry.”

Still confused, I followed my duffel bag out of the university through a back entrance and crossed the street into a military barracks. A soldier holding a machine gun saluted us and opened a razor wire gate. One of my escorts opened an apartment and set my bag down on the bed in the far room. I picked it back up.

“What are you doing?”

“Este es su departamento.”

“Huh?”

He pointed at me then pointed at the bed and spoke slowly. “Su casa.” I knew enough Spanish to realize he was trying to telling me this was my house.

“What? No. I don’t live here. I don’t want to live here. I’ll find my own place.”

The second man shook his head and motioned for me to put the bag back down on the bed. “Deje su maleta aquí por favor y regresaremos a la directora ahora. Ella puede contestar cualquier pregunta que tenga.”

“What? I just . . . I’m just a teacher. Why am I here? Do you speak English?”

He motioned for me to follow him and said, “Aquí es su habitación y màs tarde le mostraré la cantina donde nosotros comemos.”

I stood in the room for a few extra seconds. There were no windows, the walls were painted a dull orange, and the only furnishing besides the bed was a dirty carpet that matched the walls and stunk like a wet dog in need of a bath.

When I got back to the university, my new boss explained that while my students would be civilian, the university was run by the military. The university, called ESPE, was short for Escuela Politécnica del Ejército. As it turns out, ejército means army.

ESPE was founded in 1922 as a military school that specialized in engineering. In 1972 it began admitting civilians and transitioning into a private university. By the time I arrived almost all the students and faculty were civilian except for a small group of segregated classes of military engineering students and the top administration officials.

“Why didn’t you tell me this before?” I asked.

“The Dean is a military officer but that’s not important, it’s a normal university. I didn’t think it would matter to you.”

I was fleeing a life in New York in large part because I hated what I perceived as the militarization of everyday life and the acceptance of perpetual war. How could I politely articulate that the idea of living in a military barracks was repulsive?

“I’m going to find a different place to live.” I told her.

My experiences in Cuenca had been fairly sheltered because of the job I held and the company I kept. When I went out, it was usually with my housemates or coworkers to drink beer, speak English, and marvel at our own greatness for being able to live in such a different place all on our own.

I cannot think of a smoother transition to life in Ecuador than the one I had in Cuenca, revolution and all. Almost everyone finds comfort in community and Cuenca was great for that. There was always someone who had a similar experience, someone to lend advice, someone who understood. Part of the draw of Latacunga for me had been the simple fact that no other foreigners lived there and I would be forced out of my comfort zone.

My experiences in Cuenca were filled with hey-isn’t-it-weird-that-they-do-that-here bonding, but not so in Latacunga. Shortly after I arrived I learned that since there were no scheduled garbage pick-ups the municipal trucks would play a song to let everyone know they were coming and to ready their garbage. The song was already familiar to me; it was the same one that ice cream trucks played in the U.S. “Isn’t that weird?” I would ask after explaining the irony that the song that I identified with dessert meant waste disposal in Latacunga.

No one ever thought it was weird. I stopped asking.

I hated walking through the barbed wire gates to come home to the housing the university had provided. I hated seeing the solider standing there with a gun every day. When I opened my apartment, I walked straight to my room and shut myself in. The common bathroom did not have a door and the only time I saw the two soldiers I shared the apartment with was when I was sitting on the toilet or naked in the shower.

A few days after I moved in I became ill from drinking the water and had severe diarrhea. The plumbing system throughout Ecuador used smaller pipes so that flushing toilet paper would clog and cause the soiled water to flow back out. Next to the toilet I piled feces-stained paper into an overflowing bucket. I never spoke with the soldiers, but they slowed their step at the open bathroom door, staring in on the strange new foreigner occupying their toilet.

Attached to the shower head was a plastic casing the size of my fist with wires running out of it. The water was heated with electricity—the same as I had seen in Cuenca. But there was something wrong with my shower in Latacunga. Every few minutes something would catch and a jolt of electricity would pulse through the water and shock me. It was always just a fraction of a second but I never knew when it would happen and my body would tense up as soon as I turned on the water. The two soldiers took their towels and soap next door; but I had no place else to go.

I met Veronica again but had trouble making friends, in large part because of my poor language skills. I spent time walking around the city or sitting in the park reading when I was feeling well, but that wasn’t very often. I probably had a calorie-deficiency because I was consuming less meat and much of what I did eat turned to diarrhea as my body adjusted to the water.

There was an issue at the university and my workload was reduced to a single class. I taught ‘conversation’ and enjoyed moderating and encouraging discussion. It was usually the best part of my day. But after class, for lack of anything better to do or lack of energy, I would walk across the street into the military barracks and struggle to make sense of the Spanish-language newspapers I was trying to learn from.

I considered giving up. I thought about catching a bus to Quito and getting on the next plane to New York. All the things that drove me away from the United States were still there, but just about anything else looked attractive compared to the view from the toilet seat in the military barracks. The thoughts never lasted long, but for fleeting moments the most powerful emotion I felt was solitude and it made me long for the familiar.

Three weeks after I began working at the university there was a knock on my bedroom door. It was a man I had met in the park two days previous. His name was Kleaber (pronounced ‘clever’) and he was wearing jeans and a second-hand suit. A collared shirt was tucked into the jeans, just the same as the first day we met. Though he was only a few years older than me he combed his black hair over his forehead to try and cover a quickly receding hairline.

“Hello John! How are you doing?!” he said with a little too much gusto. Kleaber had taught himself English and spoke it perfectly—even better than many professors at the University level.

“Umm. I’m alright.” After a brief pause I continued. “How did you find me?”

“Well you said you worked at ESPE so I went there and asked around for you.” He poked his head into the doorway. “May I come in?”

“Oh, okay,” I said, still somewhat surprised at my first visitor. “Sure, come in.”

“I have a business proposition for you.” He sat on the couch in the foyer. It was the first time I ever saw anyone sit there.

“Sure,” I said, and sat down in a wooden chair across from him.

Kleaber ran a one-man English school. He organized classes, tutored individuals and would help with homework. He had even dressed in disguise and taken proctored exams at various schools. Anything for the right price.

“I have two students who want to learn from a native speaker. The pay is pretty good—would you be interested?”

I agreed out of boredom as much as anything else but the prospective students never turned up and I never taught them. Still, Latacunga was small enough that I would bump into Kleaver quite often. He would confirm an answer on a difficult homework question or ask me to define a new word he saw on a message board he visited online. I had questions for him too. Which bus to take; how much things cost; and where to find certain markets. Often this would happen while I was sitting in the park, either reading or watching the town walk by. When I ran into him near the main food market one day he invited me to meet his mother and have coffee.

Two blocks north of the market we turned toward the cemetery. On one corner a woman stood behind a yellow tank of gas that connected to a stove-top. She was frying empanadas in a giant wok. Across from her another woman was grilling what looked like sausages. Beyond them, lining the north side of the street, vendors had set up flower displays on homemade wooden tables that sat where cars would have otherwise parked.

After walking a few paces past the women selling food on the corner, Kleaber’s mother saw us. She had been sitting on the step that lead into her shop but jumped up and waved her hands excitedly and shouted, “¡Ven! ¡Ven!”

Her name was Hilda, but I always knew her as la Señora. She invited us in to her crowded shop. “Sit down! Sit down!”

She ran off through what appeared to be a hole in the wall and I heard her turn on the stove. La Señora was a country girl and she was as tough as her calloused feet.

“She’s had this shop my whole life,” Kleaber told me.

Bunches of dried flowers hung on wooden sticks and dangled above. The space was only about ten feet by twenty, but it fit a lot. The cushioned bench Kleaber and I were sitting on acted as la Señora’s bed. There was a pile of blankets in the corner behind a glass case that held dried floral arrangements. Kleaber was sleeping there temporarily and English workbooks poked out from underneath the blankets.

La Señora came back with coffee and ran off again. When she returned she handed me a plate of eggs fried in too much salt. “¡Cometelo!— Eat it!” she shouted at me and then started laughing. I barely understood anything she said, but her enthusiasm and constant laughter at her own jokes in a non-stop monologue was oddly pleasant.

Kleaber’s sister Ana stopped by to say hello. She had dyed red hair and wore black leather boots that nearly reached up to her knees.

“Ana also has a store on this block.” Kleaber told me. The five brothers and sisters had grown up helping out in their mother’s shop next to the cemetery and three of them now owned their own flower shops on the same street. Kleaber had to meet a prospective student and ran off, leaving me with half a cup of coffee I still had to finish.

“I teach English also and would prefer practice if you like my store,” Ana said.

Her English, like most teachers I met in Latacunga, was lacking, but it was still much better than my Spanish.

She gave me a seat in her shop and she sat opposite me on a cross section from a large tree. The stump was about a foot tall and still had bark on the edges.

“What do you opinion George Bush?” she asked me.

I laughed. “George Bush …” I paused as if I was searching for the right word. I already knew her answer to the question and knew what she hoped I would say. It was always one of the first things Ecuadorians asked me and thus far everyone who had queried had shared my strong dislike for the U.S. president, but I let Ana hang for a second. “George Bush is a donkey.”

Ana laughed out loud. I had recently learned that calling someone a burro, a donkey, was a strong insult. “George Bush is a donkey; the politicians here are burros also.”

We chatted more and I yawned. The mountain air was thinner than I was used to. I later learned that yawning happens when your body wants more oxygen, which explains why I sometimes found myself yawning randomly when I first moved to Latacunga. Though, at the time I had no idea why.

“Do you have hunger?” Ana asked.

“No, why?”

“Because you yawned. That means you’re hungry.”

“Really? Doesn’t it mean you’re tired?”

“Are you tired?”

“No.”

“So you’re hungry then?”

“I’m neither hungry nor tired. Sometimes I just yawn.”

She smiled and gave her head a slight shake as if she knew I was just being polite. “I’ll return fast; I think there’s rice I heat you for.”

“Seriously, I’m not hungry.”

But she was already heading down the street to use the kitchen her mother had just made me eggs in.

A month after I moved into the military barracks, Kleaber spoke to the university on my behalf and helped me find a room to rent.

The room was simple and I liked that. It had been an unused alcove between two other bedrooms above a street-side restaurant. With my deposit the landlord bought wood and nails and built a wall out of plywood and two by four lumbers to create my room. He showed me what paint he already had and I chose to cover my windowless room in sky blue. An old bed and dresser, collecting dust in the space before the fourth wall was built, stayed and became my own.

There was a community kitchen across from my new room, a communal bathroom down the hall and a concrete basin with running water on the roof for washing clothes. I immediately set about teaching myself how to cook.

In Cuenca, while I was contemplating borders and deciding to begin my new life ignoring their authority, I also started to think about food differently. In the markets, freshly killed chickens hung upside down in clear plastic bags. They were already plucked of their feathers, often by dipping their body in boiling water, sometimes while still alive, but everything else was still intact. Blood drained from their lifeless body through a slit in their neck and pooled in the corner of the bag. In the countryside outside of Cuenca I had my first up close experience with cows and helped a friend yank a baby calf away from its mother—so there would be more milk to sell. The week-old calf desperately struggled to stay close, ignoring the rope tied around its neck that we pulled it away with.

Henry David Thoreau’s message from Civil Disobedience—that when you oppose an unjust system the true revolutionary act is not to fight against it and lend legitimacy through recognition of its authority, but to completely withdraw from it—guided me not just with borders but with everything I tried to do in my new life. In the U.S. I had been disturbed by the treatment of animals that would eventually end up on our dinner plates. I made sure to avoid veal and always buy cage-free eggs, and hoped that would help bend things in a more humane direction. In Ecuador, I decided to walk away completely. I stopped eating meat.

None of the Ecuadorians I met understood why I chose to remove myself from a system that boiled chickens alive and choked calves trying to stay with their mother, and only the rare vegetarian restaurant would serve a meal I could eat, but I was learning quickly that Ecuador, with its tropical coast, cool mountains and year-round growing season, had excellent food for me, if I only learned to prepare it all myself.

Life had never seemed as raw as it did my first few months in Ecuador. Many of the accepted norms that I had grown up with seemed to no longer apply. My paychecks never arrived on time and despite having plans, my new acquaintances would show up late or not at all. The foreign language director would schedule a meeting and arrive an hour late without a word. For months I refused to get a cell phone because I wanted to break from consumerism and have as few possessions as possible, so I relied on meeting people at specific places and times—which was a horrible idea in a land where everyone was always late. Intersections often didn’t have stop signs or traffic lights and I didn’t know how to cross through the steady traffic. Prices in the market and many stores were unmarked and since I didn’t yet know to haggle, I was always overcharged.

I had crossed my first border many months earlier, on an airplane flying into the sprawling capital, but it took moving to Latacunga to feel the new world and really breathe in its nuances. Over the coming years, as I adjusted to a new culture and set of priorities, I began to like these norms more than the ones I had grown up with, but in the beginning, I was, like most cross-border travelers, judging a new place by an old standard. I didn’t yet understand that one wasn’t better or worse, just different. As time progressed, I would stop to talk with a neighbor I saw on one corner and then a friend’s cousin on the next, caring more about the small human joys we shared in casual conversation than the meetings I was already late for, and finally, I began to understand. But my appreciation for community and everyday changes in perception developed slowly. For the most part early on, I was just frustrated. Then I met Lucía.

--

I'll be releasing the entire book this way but if you want to buy the paperback with Crypto-currency, email: [email protected] with your mailing address (U.S. only) and your preferred crypto and I'll respond with a wallet address and mail the book. $10 USD including shipping, limited time/ crypto only

Deleted

@johndennehy you are doing a great work. Keep it up buddy. I am happy to see you successful.

Cheers Mate

Regards, @momimalhi

Great and awesome post

Love story cross border has always been successful , it’s good story , looking forward to learn something from you

Big thinking

Border crossing ... zero experience ... you got nerves man.

Thanks @fahan.sidiqui but I was also 22 and had little experience in the world so I think we can add naivete to the mix as well. A lot of lessons were learned.

yes @johndennehy ... you are ready to see the world full of colors ... keep learning keep growing.

Sorry folks, I let a typo slip in. To clarify this is the fourth installment (not the second). Here are links to the first three: [Prologue | Ch 1 | Ch 2]

I wish you all the best and lots of success for your book :)

Thanks @ohmygoodness

You got a 25.78% upvote from @postpromoter courtesy of @johndennehy!

Want to promote your posts too? Check out the Steem Bot Tracker website for more info. If you would like to support the development of @postpromoter and the bot tracker please vote for @yabapmatt for witness!

To listen to the audio version of this article click on the play image.

Brought to you by @tts. If you find it useful please consider upvoting this reply.