Success Through Failure

"Nothing succeeds like success" is an old saw with many different teeth—some still sharp and incising, some worn down from overuse, some entirely broken off from abuse. In fact, the saying borders on tautology, for who would deny that a success is a success is a success?

image source

We know success when we see it, and nothing is quite like it. Successful products, people, and business models are the stuff of best sellers and motivational speeches, but success is, in fact, a dangerous guide to follow too closely.

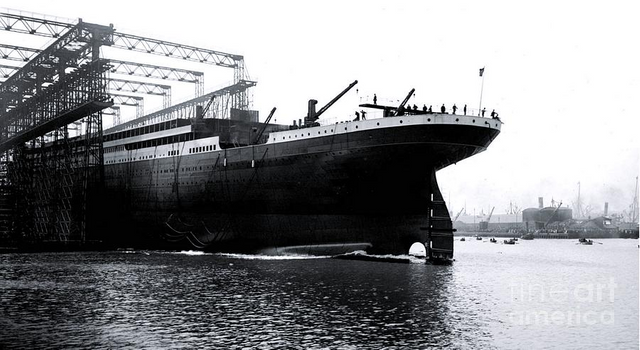

Imagine what would have happened if the Titanic had not struck an iceberg and sunk on her maiden voyage. Her reputation as an 'unsinkable' ship would have been reinforced. Imagine further that she had returned to England and continued to cross and recross the North Atlantic without incident. Her success would have been evident to everyone, and competing steamship companies would have wanted to model their new ships after her.

Indeed, they would have wanted to build even larger ships— and they would have wanted to build them more cheaply and sleekly. There would have been a natural trend toward lighter and lighter hulls, and fewer and fewer lifeboats. Of course, the latent weakness of the Titanic’s design would have remained, in her and her imitators. It would have been only a matter of time before the position of one of them coincided with an iceberg and the theretofore unimaginable occurred.

image source

The tragedy of the Titanic prevented all that from happening. It was her failure that revealed the weakness of her design. The tragic failure also made clear what should have been obvious— that a ship should carry enough lifeboats to save all the lives on board. Titanic’s sinking also pointed out the foolishness of turning off radios overnight, for had that not been common practice with the new technology, nearby ships may have sped to the rescue.

A success is just that—a success. It is something that works well for a variety of reasons, not the least of which may be luck. But a true success often works precisely because its designers thought first about failure. Indeed, one simple definition of success might be the obviation of failure.

Engineers are often called upon to design and build something that has never been tried before. Because of its novelty, the structure cannot simply be modeled after a successful example, for there is none. This was certainly the case in the mid-nineteenth century when the railroads were still relatively new and there were no bridges capable of carrying them over great waterways and gorges. Existing bridges had been designed for much lighter traffic, like pedestrians and carriages. The suspension bridge seemed to be the logical choice for the railroads, but suspension-bridge roadways were light and flexible, and many had been blown down in the wind.

British engineers took this lack of successful models as the reason to come up with radically new bridge designs, which were often prohibitively expensive to build and technologically obsolete almost before they were completed.

The German-born American engineer John Roebling, the bicentennial of whose birth is being celebrated this year, looked at the history of suspension-bridge failures in a different way. He studied them and distilled from them principles for a successful design. He took as his starting point the incontrovertible fact that wind was the greatest enemy of such bridges, and he devised ways to keep the bridge decks from being moved to failure by the wind.

Among his methods were employing heavy decks that did not move easily in the wind, stiffening truss work to minimize deflections,and steadying cables to check any motions that might develop. He applied these principles to his 1854 bridge across the Niagara Gorge, and it provided a dramatic counterexample to the British hypothesis that a suspension bridge could not carry railroad trains and survive heavy winds.

The diagonal cables of Roebling’s subsequent masterpiece, the Brooklyn Bridge, symbolize the lessons he learned from studying failures. Ironically, the Brooklyn Bridge, completed in 1883, served not as a model of how to learn from failure but as one to be emulated as a success. Subsequent suspension bridges, designed by other engineers over the next half century, successively did away with the stay cables, the truss work, and finally the deck weight that Roebling had so deliberately used to fend off failure.

Resources

Credits go to HENRY PETROSKI's book - Success Through Failure

https://appel.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2013/05/NASA_APPEL_ASK24i_success.pdf

Thank you for reading. I hope you have learned a thing or two as I look forward to seeing you leave feedback that can add more value to this post.

Have a spare time? You may check these:

- Theories Regarding Personal Confidence: How Are Self-confidence, Self- esteem, and Self-efficacy Important In The Business World

- War Against 'Fake News': The Difference Between Fact And Opinion In The News

- 'Fake News' Is A Symptom Of 'Lack Of Media Literacy' - How Did 'Fake News' Originate?

- Fake News And The Commonly Asked Questions Regarding It

- Personal Confidence and Motivation In The Business World

- African Nations Abandoning Agriculture And Their Reliance On Natural Resources - The Source Of The Ever-growing Problems In Africa

- Academic Intelligence VS Creative Intelligence: Why Drop-outs Have Been Known To Emerge as Great Inventors Later In Life

- Steemit Has Given Us A Better Life - Let's Reach Out To The Poor And Needy

- Time To Face The Fact: Here Is What Is Hampering The Eradication Of Illiteracy In African Nations

- The Rising Wave Of Violence In Our Tertiary Institutions: No Man Beat Up His Parents And Made Headway In Life...

I am @teekingtv, the no.1 Global Meetup analyst

I request for your feedback through comment. And I may get you arrested for ignoring this post.