Feeling Colonial in 1918

The Colonial Revival

Looking through the advertisements in the Philadelphia Inquirer from 1918, I kept noticing items described as "Colonial." From "Colonial Water Tumblers" to a "Colonial Brass Bed" and "Colonial Design Dresser," these goods evoked a time gone by.

Advertisements from the Philadelphia Inquirer January 4th and 6th, 1918

They represented part of the Colonial Revival, an aesthetic movement which prized association to America's earliest days, and which lingers yet today in the worlds of architecture and antiques. The obsession with the story of American independence, while it perhaps never faded completely from American memory, seems to have been inflamed anew around the middle of the nineteenth century.

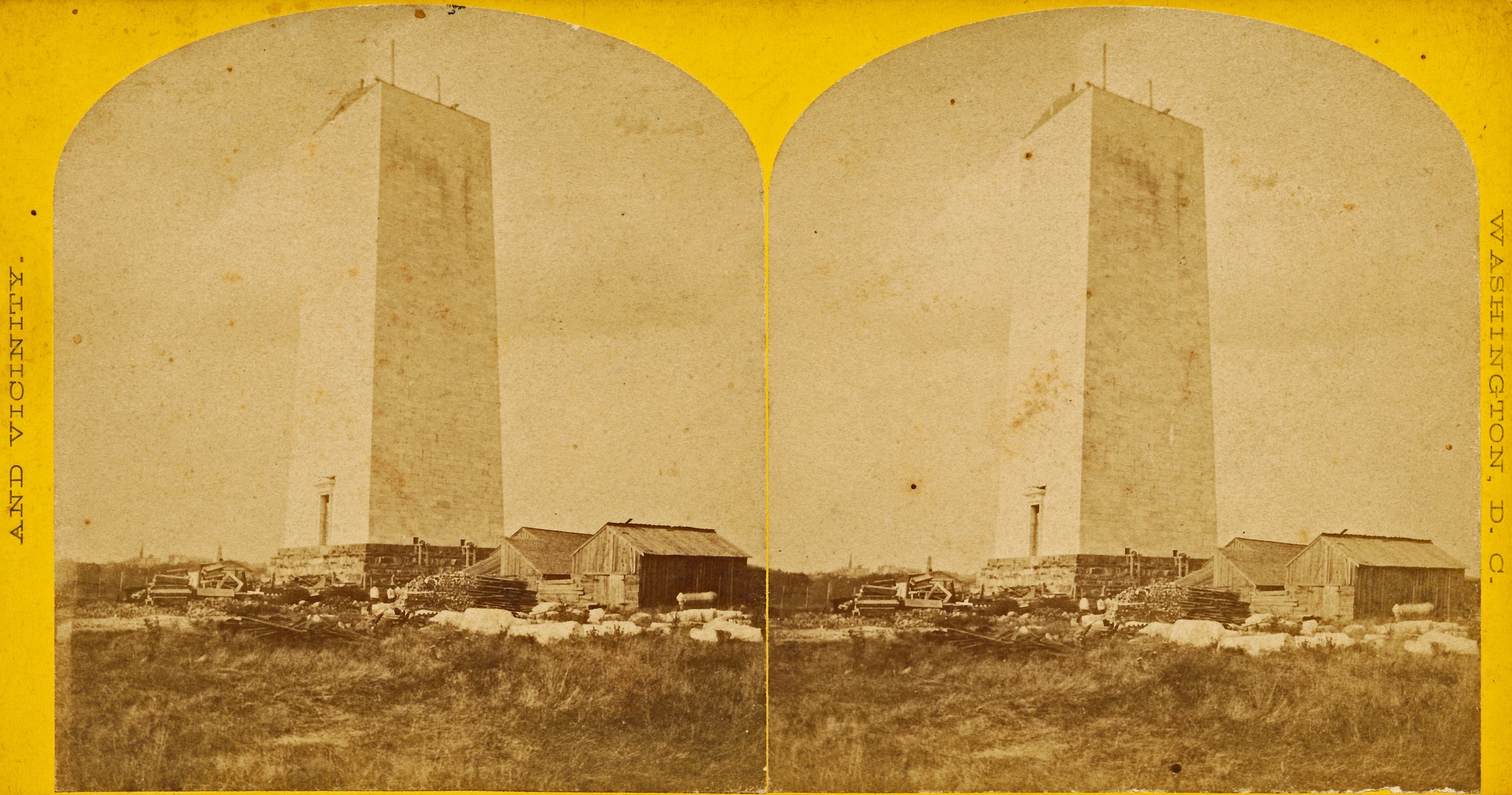

First, the last of the Revolutionary generation died out. George Robert Twelve Hewes, a young shoemaker in the 1770s, became a celebrity in the late 1830s upon the publication of two accounts of his part in the revolution.[1] By the 1850s, the base of the Washington monument had been laid and preservationists campaigned to protect Mount Vernon.[2]

Stereogram of the Washington Monument as it appeared between 1848 and 1884. Image via StreetsofWashinton under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC 2.0

Following the American Civil War, reverence for Washington and Colonial America in general would reach a fever pitch as relics from the great man were put on display, first at the United States Patent Office (then one of the few fire-proof buildings in Washington, DC) and then at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876. Colonial fashions and souvenirs would be standard fare at the succession of expositions over the next decades, juxtaposed jarringly with the newest products of industrialization.[3]

American Aesthetics

The late 19th century saw a rise in historic preservation, both in the form of shrine-making--as at Mount Vernon--and in the form of measured drawings. The study of the oldest American buildings became a search for an intrinsically American architectural form, and homes such as Mount Vernon became imbued with not only notions of aesthetic merit but of American essentialism.[4]

Photo of Mt. Vernon by "m01229" used via Creative Commons license CC BY 2.0

The connection between architectural form and culture made Colonial style into a potent symbolic vocabulary by the turn of the 20th century. In an era of prescriptivism in the form of instructional manuals and early home decor catalogs, Colonial Revival houses and furnishings became not only symbols of good taste but also of good morals. The movement to preserve American homes, both in situ and reconstituted in art museums as period rooms was based on the idea that these surroundings could educate the masses on how to be American. Louisa May Alcott's family home was restored explicitly to indoctrinate the children of immigrants in the ways of American Culture.[5]

Colonial America has remained a potent symbol, its images evoked throughout the Cold War Era and as recently as the last decade, with the Tea Party Movement within the Republican Party.

1918 Colonial America

Let's return to 1918. A search for "colonial" in that year's issues of the Inquirer turns up a few other uses of the adjective, as on January 13th in an article titled "New German Policy Proves Menace to the Whole World," which discusses the colonial territories of various European powers being contested during the Great War.[6]

What does not appear in a search for "colonial" is another relevant meaning of "colonial America" in 1918: America as colonizer rather than colonized. In the wake of the Spanish American War nearly two decades before, the United States's imperial power stretched across the globe, adding Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines to Hawaii as territories under its control. In the decade before WWI, the United States added territories such as American Samoa and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

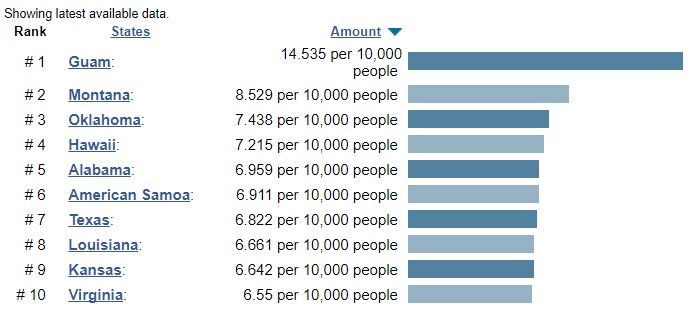

Eventually Hawaii would gain statehood and the Philippines would claim independence (that's a very long story) but many American territories remain, essentially, colonies. Guamanians serve in the American armed forces at almost double the rate of other American citizens but their only representative in congress is a non-voting delegate. [7]

Graph from Statemaster.com with data from the National Priorities Project Database, 2004

What did it mean in 1918 for Americans to lift up styles from an era in which they felt oppressed as their country perpetrated oppression? It is worth noting that American imperialism has often had racist overtones. For instance, in 1918, the occupants in the territories mentioned above were not U.S. Citizens but U.S. Nationals and could thus neither vote or run for office.[8]

What does America's colonial history mean for 2018?

Politicians are fond of citing the intentions of the "founding fathers" as they debate legislation. Colonial Williamsburg is still selling "reproduction" furniture even as it faces financial uncertainty. And many Puerto Ricans are still without power after a devastating hurricane was followed by slow mobilization of federal disaster management agencies.

Members of the Coast Guard distribute water in the wake of Hurricane Maria. Image from Coast Guard News under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Today as in 1918, America's colonial pasts are entangled. What might we learn by considering the American colonies of the 18th and 20th centuries in the same space? For one thing, I suspect that the American citizens who live in our territories might have insights on taxation without representation.

100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History Initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment conducted by graduate courses at Temple University's Center for Public History and MLA Program, is exploring history and empowering education. Click here to learn more.

Notes

[1] Alfred F. Young, The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution, Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1999.

[2] Savage, Kirk. "The Self-Made Monument: George Washington and the Fight to Erect a National Memorial." Winterthur Portfolio 22, no. 4 (1987): 225-42. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1181181; Patricia West, Domesticating History: The Political Origins of America’s House Museums (Washington [D.C.]: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1999).

[3] Karal Ann Marling, George Washington Slept Here : Colonial Revivals and American Culture, 1876-1986 (Cambridge, Mass.: Cambridge, Mass. : Harvard University Press, 1988).

[4] Lydia Mattice Brandt, First in the Homes of His Countrymen: George Washington’s Mount Vernon in the American Imagination, Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2016.

[5] West, Domesticating History.

[6] Frank H. Simonds, "Enslaving Slaves German Ambition; Menace to World. Teutons Seeks Early Peace Which Shall Leave Her Still," Philadelphia Inquirer, 13 January, 1918.

[7] "Total Military Recruits: Army, Navy, Air Force (per capita) (most recent) by state" Statemaster.com: http://www.statemaster.com/graph/mil_tot_mil_rec_arm_nav_air_for_percap-navy-air-force-per-capita ; "Guam's At-Large Congressional District," Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guam%27s_at-large_congressional_district

[8] https://www.immihelp.com/immigration/us-national.html

Looking into the Philly.com (Inquirer) database, I see the word "colonial" appears 1,160 times in 1908; 2,620 times in 1918 and 2309 times in 1928. So you may be onto something. And looking at the word "colonial" at Google Ngram shows a nice peak in 1919, But why then --- do you think?

This is some interesting information. Perhaps both searches would yield even higher results if extended to the Spanish-American war?

To top it off, the architecture imitated by Colonial Revival is generally Georgian, which was an English style you would expect to promote English, not revolutionary, values. I would say true colonial styles were the one-room frontier houses smaller than modern studio apartments, which represent a mixture of styles from Sweden, Germany, and anywhere else immigrants came from. Even slave quarters could be considered colonial architecture. They definitely don't send the message colonial revivalists wanted though.

I like where you took this post. As you know, not only does American Imperialism involve the political colonial possessions, but also the economic colonization of nations like Cuba, Guatemala, and the Dominican Republic. Talk about a word with large implications!