The Viking language and her children

By Sveinn Ullarson for Silly Linguistics

VIKINGS! They came from the land of the ice and snow, from the midnight sun where the hotsprings blow... except they didn't, not from the land of hotsprings (Iceland), not generally speaking anyway. However Norsemen certainly did! So what's the difference between Vikings and Norsemen and what language did they speak?

Let me first take the opportunity to dispell this myth going around that Viking is not a word for a people, it's an action. Everytime I hear people try to correct someone with saying “Ah! But Viking isn't something to be, it's what you do... you go a-viking!” it makes me want to tie them to a stake and set fire to the building.

Viking is a word we took straight from the Old Norse víkingr. It derives from vík which refers to an inlet or bay, and the ending -ingr which means person. Scholars are unsure whether it was meant to mean someone who sails from the bay or someone who sails INTO bays (in order to upset the locals), nonetheless we're talking about people. The confusion that it refers to an action arises from two things.

Firstly that in English we often use the ending “-ing” when talking about actions: feasting, fighting, drinking, pillaging etc. so “viking” in English can sometimes get misinterpreted in that way.

Secondly, Old Norse had another very similar word víking (identical to the first word, víkingr, but without the 'r' at the end), and this word refers to what Vikings are likely to participate in, because it essentially means “a journey or voyage with the intent to go raiding”, but still you wouldn't say you 'go' a voyage, but you can 'go on' one.

“Hó, sveinar! Vér skulum fara í víking fyrir sumarinn!”

(Alright, lads! Let's go on a raiding voyage for the summer!)

But we never borrowed this word into English, partly because it'd be confusing since we already borrowed 'Viking' for the people, and also because it's simple enough to just say “a raid” or “a voyage”.

But not every Norseman was a Viking, as it happens being a Viking was something you were most likely to do only a few times in your youth. There were the odd few who loved it so much they'd go raiding every summer until they grew old and grey, but more often than not Norsemen would reach the point when they'd say:

“Á, nú emkat svá ungr at vesa í víkingu, betr þætti mér at kvænask.”

(Ah, I'm a bit old now to be going on raids, so I'd best settle down with a wife.)

So when we talk about Viking language, it's really just a more fun way of saying Old Norse, but they spoke the language just as much when they were farming sheep as when they were looting monasteries.

The Norse language was not a harsh gutteral barbarian tongue of grunts and warcries, it was a remarkably beautiful language that produced some of the finest poetry the world has ever known. Though I would be lying if I said that the poetry did not occasionally venture into colourful descriptions of violence. Take this verse from the poem Hákonarmál for instance:

“Brunnu beneldar í blóðgum undum,

lutu langbarðar at lýða fjǫrvi,

svarraði sárgymir á sverða nesi,

fell flóð fleina fjǫru Storðar.”

“Wound-flames (swords) blazed in bloody wounds,

Greataxes struck down taking people's lives,

The sea of blood crashed against the headland of swords,

The river of arrows fell on the island's shore.”

Brutal isn't it! But in all seriousness, they weren't really such a bloodthirsty lot, no more so than anyone else in history. Look at the Crusades that came centuries after, now that was a REAL bloody mess! The Pope kept giving them all the thumbs up about it, and frankly I don't believe the situation was very different to our Vikings at all... young guys hungry for adventure, wanting to explore new lands and come back home with stories of heroism, a bucket load of souvenirs and maybe a couple cool scars to show off to the nice girls in the village.

The Norse get a bad rap. It wasn't really bloodshed and violence they glorified. They admired people who didn't back away from a fight, who didn't back out of agreements. People who stuck by their words no matter the cost and achieved what they set out to do. Earnest, brave and honest people. In those days, reputation was everything. As this famous verse of Norse poetry says:

“Deyr fé, deyja frændr, deyr sjalfr it sama.

Ek veit einn at aldrei deyr, dómr um dauðan hvern.”

- Hávamál 77

“Cattle die, loved ones die, you yourself will die one day,

but the one thing that will never die is what will be remembered of you after you're dead.

It comes from a very different culture to ours; we don't have a warrior society anymore where reputation is placed above all else, but somehow there's still a lot of truth to those words. Society changes, but people don't. And that's who the Norse were... just people. So who did they become? Who are the children of the Viking language?*extinct by around the 19th century

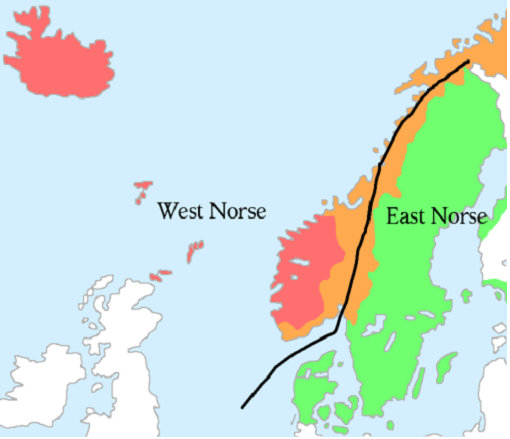

There are five languages spoken today that descended from Old Norse, six if you include Elfdalian which otherwise is classed as a dialect of Swedish. Icelandic, Faroese, Norwegian, Swedish and Danish. There was a seventh language, Norn, spoken in the Shetlands and Orkneys, but now only traces of that language can be found in words for local wildlife. Since Old Norse was spoken in two main dialects, West Norse and East Norse, it's common for linguists to categorise its children according to those two groups.

However, it's tricky as Norwegian doesn't really fit the system. It was originally a West Norse language, but over time many dialects became heavily influenced by East Norse and now the country is divided by two writing systems. West Norwegian dialects that write in Nynorsk (red) can still fit under the West Norse category, but East Norwegian dialects that write in Bokmål (orange) are perhaps better placed in the East Norse group. The model is problematic and outdated, so a better way of understanding the Norse descendent languages is this:

So Norwegian, Swedish and Danish are the child languages of Norse that remained on the continent, and Icelandic and Faroese (also Norn) are the child languages from when Norse was introduced to islands around the North Atlantic.

There was even a variant spoken on Greenland until the 15th century, but the Greenlandic Norse had all died centuries before the Danes managed to recolonise. Let's look at some of these languages by taking the same powerful words of Hávamál 77 above and seeing what they look like in each of the descendent languages.

INSULAR SCANDINAVIAN:

“Deyr fé, deyja frændr, deyr sjalfr it sama. Ek veit einn at aldrei deyr, dómr um dauðan hvern.”

Icelandic: Deyr fé, deyja frændur, deyr sjálfur ið sama. Ég veit einn að aldri deyr, dómur um dauðan hvern.

Faroese: Doyr fæ, doyggja frændur, doyr sjálvur hann somuleiðis. Eg veit ein ið aldri doyr, dómur yvir deyðan mann.

Norn*: Deu fe, duya frinder, deu shel an da samma. Yach wet ien sin allde deu, dume on daun whaar.

CONTINENTAL SCANDINAVIAN:

“Deyr fé, deyja frændr, deyr sjalfr it sama. Ek veit einn at aldrei deyr, dómr um dauðan hvern.”

Norwegian Bokmål: Dør fe, dør frender, dør selv på samme vis. Jeg vet en som aldri dør, dommen over den døde.

Norwegian Nynorsk: Døyr fe, døyr frender, døyr sjølv ein samleis. Eg veit ein som aldri døyr, domen om kvar ein daud.

Swedish: Dör fä, dör fränder, dör själv du likaledes. Jag vet ett som aldrig dör, domen över död man.

Elfdalian*: Där fä, däa fränder, där siuov summulund. Ig wet ien so older där, duomen yvyr doðkall.

Danish: Dør fæ, dør frænder, dør selv man tilsidst. Jeg ved et som aldrig dør, dom over hver en død.

I explained what the verse meant in English already but what I wrote above was too long and convoluted to count as a genuine translation of poetry, so here it is once more, this time trying to be closer to the original Norse text:

“Deyr fé, deyja frændr, deyr sjalfr it sama. Ek veit einn at aldrei deyr, dómr um dauðan hvern.”

English: Die fee, die friends, dies the self just the same. I know one, that never dies, doom upon dead men.

But isn't it funny how this translation seems like it belongs somewhere with the others above? It doesn't seem vastly different to the others. Well it isn't. It'd be a bit of a leap to start suggesting English was a child of Old Norse. When the monks first saw the Viking longboats approaching across the waves, it was English they used to beg and plead with God to protect them from the heathen invaders, but at least at that time Old Norse and Old English were sisters or at least cousins.

Whilst Norsemen said 'frændr' to mean kinsmen, Anglo-Saxons said 'freondas' to mean friends. Aside from the subtle differences in meaning between many common words, there were many words that were identical in meaning. Norsemen said 'fé' to mean livestock, and Anglo-Saxons said 'feh' to mean the same, though as this word developed into the Modern English fee, it has since changed meaning.

For the Norse and the Anglo-Saxons livestock was used as currency, so when they needed to pay a fee to someone, it was cattle that they would use, thus how it obtained its current meaning. Likewise, Norsemen said 'dómr' and Anglo-Saxons said 'dóm' to mean judgement. The modern word is 'doom' which has now shifted meaning to refer to an unpleasant fate, but this is through the idea of someone facing God's judgement, and thus 'meeting their doom'.

In my English translation above I've used both these words with their original meanings for effect, so perhaps it exaggerates the similarities between Modern English and Old Norse. But back in the past the similarities were much stronger, to the point where many people have suggested that with enough time and patience a Norseman and an Anglo-Saxon could have understood each other.

Maybe it's a bit much to say they could understand each other's languages, but they could find ways to be understood based on the common ground. What is certain is that the Norsemen who settled in England between the 9th to the 11th centuries didn't find learning the local language much of a challenge. However, since they just picked it up as they went along, it meant that they very often ended up slipping in their own words.

NORSEMAN: Ah, I think a fly bit me on the leg.

ANGLO-SAXON: You mean on the shank?

NORSEMAN: Yeah my er... skin is itchy there.

ANGLO-SAXON: Your hide you mean. The hide of your shank is itchy.

NORSEMAN: I'd better bring the hay inside. The sky looks grey.

ANGLO-SAXON: The what? What am I looking at? Clouds? Heaven?

NORSEMAN: Why do the gods always do this to me? Can't they give me a break?

ANGLO-SAXON: “Give”? “They”?! What?! I can't understand a word this dirty heathen says. I want someone to get rid of these Norsemen!

So leg, skin, sky, they, give, dirty, want, get and rid are all Norse words that entered English. We used to say “shank” for leg, and “hide” for skin before the Vikings came, and the Norse word sky, even though it originally meant clouds, replaced the word “heaven”.

Obviously we still use the words shank, hide and heaven, but they ended up being used for other things. But there are many other words that we got from Norse, this little mock conversation shows but a few. Old Norse and its descendants are classified as North Germanic languages, whereas English alongside Frisian, Dutch and German are classified as West Germanic languages.

But Modern English is very different from the other West Germanic languages, it now has a word order closer to Norse and the North Germanic languages, and a simplified verb conjugation not too different from the Continental Scandinavian languages.

So just as how Norwegian is shifting away from being a West Norse language into being an East Norse language, perhaps Modern English being categorised as a West Germanic language is also an outdated model. It might be fanciful but it wouldn't be entirely ridiculous if maybe we thought of the state of modern languages like this

*Norn is not well recorded by any means, so my translation cannot hope to be accurate at all. It is however my best attempt at a reconstruction of the language, based on the Norn fragment of the Ballad of Hildina, recorded by George Low in 1774. I will also confess that whilst Elfdalian, unlike Norn, is not extinct, it is still very difficult to get hold of learning materials on the language, and as such I am not confident with my translation here, so if anyone better acquainted with Elfdalian could correct me, I'd be most grateful.