Mining the Past for a Monumental Opportunity

“This Side Up.” An old idea for a new freedom monument.

The need to remember is as old as civilization itself. Without shared memory, there’d probably be no civilization. We sometimes find ourselves remembering too much of this and too little of that. A monument that meant something once, no longer means anything.

When shared memory in bronze and marble no longer inspires a sense of purpose, or pride…then what? What happens to our collective spirit when monuments become marginal?

It can’t be good. For us. For civilization.

That’s when it's time to get new monuments. That's when it's time to mine the past for little stories that could stand on their own as bigger stories. They might even stand as monuments.

Take the true story of Henry “Box” Brown. You might say Brown came to Philadelphia the hard way.

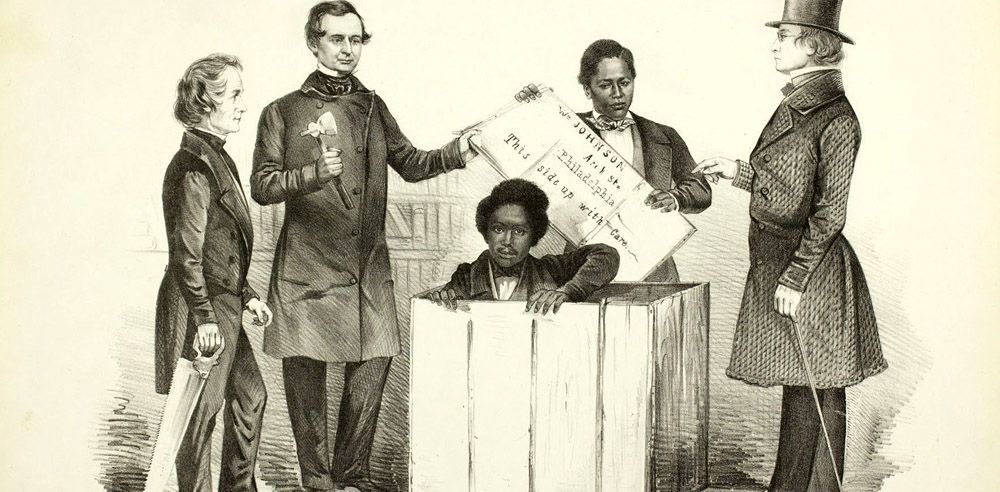

The Resurrection of Henry Box Brown at Philadelphia, (Source: The Library Company of Philadelphia)

It was 1849. A slave in Richmond, Virginia, Brown had been hired out by his owner to work in a tobacco factory. He lived with his wife Nancy and their three children (also enslaved to that man). Brown arranged to make regular payments to him in order to guarantee that the family stay together.

Nancy Brown’s owner lied. He sold Nancy, pregnant with Brown’s fourth child, as well as their other three to a Methodist minister from North Carolina who had come to Richmond on a slave-buying spree. Henry Brown got word “that if I wished to see my wife and children, and bid them the last farewell, I could do so, by taking my stand on the street where they were all to pass on their way for North Carolina.”

That was the last time Henry Brown saw his family. That was the last time they saw him.

In his grief, recalled Brown, “my thoughts were eagerly feasting upon the idea of freedom. I felt my soul called out to heaven to breathe a prayer …when the idea suddenly flashed across my mind of shutting myself up in a box, and getting myself conveyed as dry goods to a free state.”

Brown convinced two others to help him, spent his small savings on a custom-made box, “three feet one inch wide, two feet six inches high, and two feet wide.” He lined it with coarse cloth and supplied it with water and biscuits. Brown bored three small holes for air and had “this side up” painted on the top. Then, on March 23th, 1849 Brown had himself nailed in and shipped via Adams Express to Passmore Williamson, a Quaker merchant abolitionist, at 7th and Arch Street in Philadelphia.

"This side up," proved only so effective. Twice during his journey Brown found himself “put with his head downward." One time he "succeeded in shifting his position; but the second time [he] was on board of the steam boat, where people were sitting and standing about the box, and where any motions inside would have been overheard and have led to discovery.” Brown chose to “keep his position” - a decision he later said nearly killed him.

The box arrived at 7th and Arch Streets before dawn after a 27-hour journey. Brown heard the words, "let us rap upon the box and see if he is alive.” Someone knocked on the box.

Brown heard the question: "Is all right within?"

He responded: "All right."

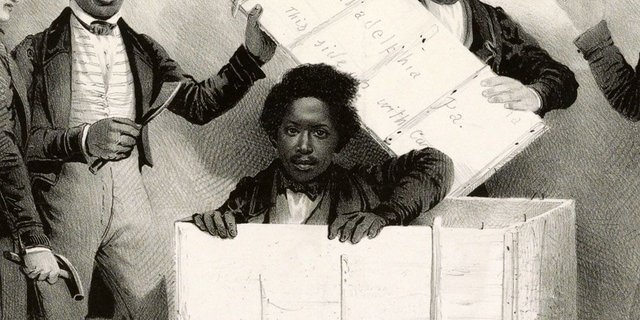

The resurrection of Henry Box Brown at Philadelphia, who escaped from Richmond Va. in a bx 3 feet long 2 1/2 ft. deep and 2 ft wide (Source: The Library of Congress)

“The joy of the friends was very great when they heard that I was alive,” Brown recalled. “They soon managed to break open the box, and then came my resurrection from the grave of slavery.”

“I rose a freeman … I had risen as it were from the dead.”

In the light of freedom, Brown greeted Williamson and his other enablers, said a prayer and sang a psalm. Brown would soon join the abolitionist speaking circuit. Over time, he created and re-created different versions of his free self: “Professor Henry Brown,” “The King of All Mesmerists,” “The African Chief,” and “Dr. Henry Brown, Professor of Electro-Biology.” According to historian Martha Cutler, Brown “created a trickster-like presence and an ever-changing, innovative performance art that melded theater, street shows, magic, painting, singing, print culture, visual imagery, acting, mesmerism, and even medical treatments.” He moved to England, living there for almost as long as he was enslaved in Virginia.

Federal Detention Center, 7th and Arch Streets, Philadelphia. Source

Today, Passmore Williamson’s office on the corner of 7th and Arch is long gone. In its place stands a Federal Detention Center “designed to hold ... inmates prior to or during court proceedings, as well as inmates serving brief sentences.” The 12-story building is connected to the nearby James A. Byrne Courthouse by underground tunnel. The public never sees the inmates who occupy, ironically, 628 box-like cells, each 96-square-feet.

The sidewalk at 7th and Arch is very much still there. And it seems to be crying out for a pre-dawn delivery, a monument in the form of a box with the words “This Side Up.”