Philanthropy: Praiseworthy Or Propaganda?

PHILANTHROPY: PRAISEWORTHY OR PROPAGANDA?

CHAPTER THREE

There is a tendency for rich philanthropists to become patrons of things that primarily interest the upper classes, while ignoring issues affecting the poor even though such issues are usually much more urgent. We saw this attitude in part one, when we talked about the philanthropic ventures of the 19th century Robber Barons. As you may recall, they mostly donated to elite schools, concert halls, museums and stuff like that. People like Carnegie also showed zero interest in tackling issues outside of their own city.

(Carnegie Hall. Image From wikimedia commons)

Given the period in which these men lived, they can be forgiven for being so localised in their philanthropy. After all, this was long before the age of smartphones and global communications networks, so people were nothing like as aware of issues like poverty in Africa as we are today.

But while we might forgive such blinkered philanthropy back then for the reason given, it’s much harder to justify it now. And yet it still occurs. According to Ken Stern’s article in The Atlantic (“Why The Rich Don’t Give To Charity”), in 2012 “not one of the top 50 individual charitable gifts went to a social-service organisation or to a charity that principally serves the poor and dispossessed”.

It would be incorrect to say philanthropists never turn their attention to such issues, because they sometimes do. There is, for instance, the Omidyar Network (brainchild of EBay founder Pierre Omidyar), pursuing such things as microfinancing which could potentially unlock opportunity for people who cannot access traditional financial and banking outlets. Another example would be the Rockefeller-backed Acumen fund, which is a for-profit company that only invests in businesses that manufacture and sell, at affordable prices, products and services needed in the developing world (things like mosquito nets and reading glasses). Of course, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s multibillion dollar commitment to tackle malaria can also be counted among the charitable ventures focused on problems that really matter.

All such examples of worthy causes should of course be commended. But the emphasis on charity as the means to deal with the fallout from the negative consequences of market competition arguably evades the more pressing question, which is ‘why is such intervention necessary to begin with?’. A cynic might say that throwing money at those affected by the negative externalities that are virtually inevitable when people are engaged in a competition to selfishly their own fortune via whatever method can be gotten away with, operating within social structures that already disproportionately favour a minority of greedy, ethically-dubious people, is akin to giving up and managing the symptoms of a socioeconomic disease rather than seeking out its root and curing it outright. It is sort of like having an engine that is leaking oil and you choose to constantly add more oil rather than fix the engine.

As to the root causes, those who have researched the systemic causes of today’s problems have traced the root back to incompatible assumptions that have held since the Neolithic period. We find one of these assumptions contained within the definition of the word ‘economics’, which is the ‘study of the allocation of scarce resources’. Along with the assumption of scarcity there is a potentially incompatible assumption applied to growth, which is that it is infinite.

The reason why the assumption of scarcity is incompatible with the assumption of infinite growth should be so obvious as to not need spelling out. But as our current consumerist lifestyles are using up vital resources far beyond sustainable rates, the obviousness must not be all that graspable, so perhaps we should express the contradiction between assumptions of scarcity and assumptions of infinite growth. Growth cannot be sustained indefinitely in an ever-accelerating fashion if it relies on something of finite supply. Eventually that supply will be exhausted and the growth must come to a stop. It is worth noting that it really does not matter how large that finite supply is, infinite growth is always by definition infinitely greater. Therefore, people who dismiss concerns about how unsustainable our economic systems based on infinite consumption are, because we can try and gain access to the much larger resources of the solar system or the galaxy or the visible universe (assuming that is even remotely practical an aim to begin with), miss the crucial point that infinite growth in consumption will exhaust any physical resource. Only infinite resources can sustain infinite growth, but then we would have to abandon the assumption of scarcity, returning us to the essential point of scarcity and infinite growth being incompatible beliefs.

For most of human history since the Neolithic period, it did not much matter that we operated under such contradictory assumptions, because we lacked the practical ability to do much harm. Up until the Industrial Revolution, populations were caught in a ‘Malthusian Trap’. It was named after Thomas Malthus, who argued that population growth would outrun the ability to provide enough essential resources to sustain that growth, leading to famines and other calamities that would reduce the numbers of mouths to feed to more sustainable levels.

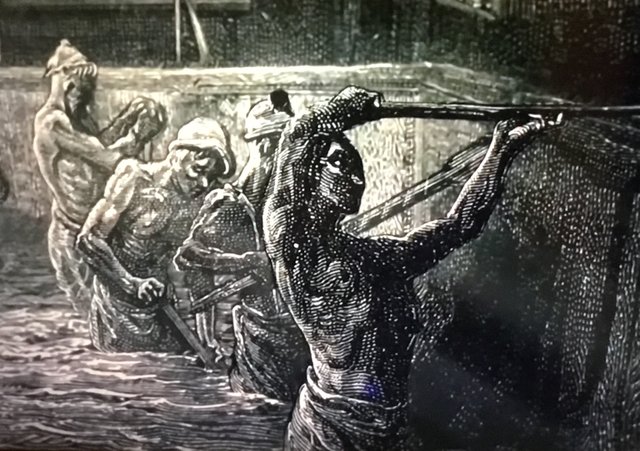

Going back beyond the Neolithic period, we are talking about a period of time when human populations consisted of small groups of tribes and bands. When populations are small and their capacity to take is restricted, Earth’s resources can seem endlessly bountiful, as indeed they are if the capacity to take is restricted to levels below that of the Earth’s ability to replenish resources. Hunter-gatherers fishing with rods and nets couldn’t even begin to affect fish stocks in an impactful way.

But it’s quite a different story when your pursuit infinite growth in consumption of fish in the interest of ever more profit has resulted in fish-catching technologies that can capture hundreds or thousands of tons of fish. There was about 1.8 million tons of spawning cod in the Grand Banks when the first commercial fishing ships capable of capturing such prodigious amounts appeared in 1951. By 1991, it was down to 130,000 tons and a year later the Canadian government had to step in and close the Grand Banks to cod fishing, or else the species would have been fished to extinction. But that decision came with consequences too, because it meant that 32,000 fishermen were thrown out of work and required billions of dollars in aid to support their families. You can see in this sorry tale how dangerous the assumption of infinite growth is when subjected to a finite resource. I would also point out that the pursuit of more profit could well have been fed by the dwindling supplies of cod, for the more scarce this in-demand resource became, the more expensive and worth pursuing it would be. That would incentivise more profit-seeking fishermen to pursue and catch the prized fish, in a positive feedback loop that either ends in the extinction of cod or government/social intervention to halt this unsustainable consumption.

(Image from wikimedia commons)

Another root cause has to do with how societies have been structured since the Neolithic period. I have covered this in detail in my series ‘This Is What You Get’, so search for that if you want more details, but suffice to say that societies have tended to be ‘redistributive’. That is, they are societies in which the populace can be divided into two groups: A non-producing elite who wield great political power and social influence, and who receive ‘tribute’ and get to disproportionately determine how it should then be redistributed to the rest of the populace (hence ‘redistributive’ societies). And, on the other hand, everybody else, the producing masses, toiling for minimal reward and who wield comparatively little social influence and political power.

This hierarchical structure has held (with some modifications, though none that truly affect its essential form) through every form of society since the Neolithic period. From the abject slaves and ruling monarchs of Egypt, to the vassals and lords in medieval feudal societies, to the handicraft merchants and state monopolists of mercantilism and on to our contemporary with the growing numbers of precariat employees and a rapacious elite in the financial and banking sectors, we see broadly the same thing, which is a society in which there are people who work and then there are those other people (always much smaller in number but far more powerful in other ways) who gain the lion’s share of the reward generated by that work. In short, it is a systemic framework that assures the superiority of a minority for whom the temptations of kleptocracy (stealing from the people they rule) is all too often a siren song they cannot resist. Even communism, which was vaguely imagined to operate very differently, turned out not so different in practice. In capitalism you get bossed by business people and in communism you get bossed by bureaucrats. Either way it is a redistributive society comprised of those who do the work on one hand, and the non-producing elites who disproportionately control fruits of that work on the other.

Stanford neurologist Robert Sapolsky, summarised the issue in the following way. “Agriculture allowed for the stockpiling of surplus resources and thus, inevitably, the unequal stockpiling of them. Stratification of society and the invention of classes. Thus it has allowed for the invention of poverty”.

(Image from ‘Why Poverty?’ Documentary)

Ever since, the presence of a powerful elite with kleptocratic tendencies, running societies on the incompatible assumptions of scarcity and infinite growth, have worked to sustain poverty rather than truly to eradicate it. This should not be thought of in terms of conspiratorial plotting. Rather, it is the evolutionary outcome of the selfish pursuit of material wealth via whatever method can be gotten away with, let loose in societies with a pre-existing disproportionate advantage for some that changes the psychological makeup of the rest in ways that lead to unsustainable exploitations of the poverty that cannot be eradicated, for to do so would be to bring down the very system that the elites depend upon for their position.

REFERENCES

“Greedy Bastards” by Dylan Ratigan

“Abundance” by Peter Diamandis and Steven Kotler

“The New Human Rights Movement” by Peter Joseph

“Guns, Germs and Steel” by Jared Diamond

“The Meaning of the 21st Century” by James Martin