Aero #1 Review

When Marvel announced its trifecta of Chinese superheroes, I braced myself to be disappointed. In recent times, Marvel has continually delivered comic series emphasising social justice in lieu of storytelling, and I was sure these comics would continue in that grand tradition.

Looking at Aero #1, I do declare I was wrong.

It was worse.

Easy on the Eye

Aero #1 comprises of two stories packed into the same issue: the headline story, plus a companion piece titled Aero & Wave: Origins and Destinies. This review focuses exclusively on the former story, as Aero only has a cameo appearance in the latter.

Aero #1 is a clear departure from Western comic aesthetics. In the huge eyes, angled noses and slender bodies, you can see influences from Asian comic styles. To the relief of hot-blooded males everywhere, Marvel decided to go against the grain of uglified superheroines, portraying Lei Ling, alias Aero, as a classically feminine beauty.

Every page in the comic is a work of art. The lines are clean, the colouring is excellent, and each panel flows easily to the next.

The cynic in me says Marvel is attempting to appeal to the Chinese market. There is a market of hundreds of millions of potential comic fans in China, eager to see what the comic heavyweight can dish up -- but are repelled by social justice design trends of chunky, unattractive female characters. The artists chose an Asian aesthetic to appeal to their target audience. Nonetheless, regardless of their reasons, the result is still striking compared to recent offerings from Marvel and other comics giants.

Unfortunately, this is all the praise I can offer.

#Story? What Story?

The most glaring flaw of Aero #1 is that there is no story.

There are two chains of events in this book. The first follows Aero fighting skyscrapers turned to monsters in her home city of Shanghai, culminating in an up-close encounter with an eldritch abomination. The second walks the reader through a day in her life, showing off her civilian career as a high-flying architect with a beautiful boyfriend.

And that is all.

There is a fight scene, a day-in-the-life sequence, another fight scene. And that's it.

No character interaction. No plot points. Little drama. No intersection between civilian and superhero life. Nothing of substance.

Both event chains could have been easily linked together. Start with the fight scene, then rewind to events a few hours before. Lei Ling finishes her day job, uses her powers to rush to her date, and enjoys dinner. Then the monsters show up, forcing Lei Ling to dump her date and switch into superheroine mode.

The transition from civilian to superhero is a stock sequence in superhero tales. The superhero is minding his own business or tending to his civilian life when a crisis erupts nearby, forcing him to act. In the space of a few pages, this creates character depth for the superhero, when we see his ordinary life, followed by drama and tension, with the superhero forced to preserve his identity and save lives and defeat the bad guy, culminating in the pay-off of a big fight scene. Bonus points if he also has to juggle his personal relationships as well.

With sharp limits on pages and panels, there is no room to have meandering day-in-the-life sequences; economy of storytelling is paramount in comics, making the transition from the mundane to the extraordinary a vital component of superhero stories.

By setting the flashback sequence three months prior to the opening, and without introducing a clear link between the two event chains, the writer scuttled all possibility of a story.

And in exchange, he portrayed a shallow woman.

Monologues with A Narcissist

Aero #1 takes the art of monologuing to the extreme. You can count on the fingers of one hand the number of panels with conversation in it.

In exchange, nearly every panel contains monologue.

Of the wrong kind.

Comics tell their stories through imagery and action. Text comes dead last. Done correctly, monologues reveal what a character thinks of the current situation and grant insight into his state of mind. They reveal information that isn't immediately obvious to the reader, especially information that enhances his reading experience.

Aero's monologues are mainly self-pleasuring mental chatter.

Many of the text boxes are variations of I have this, I have that, I can do this, I have done that. This is especially pronounced during the flashback chain, where Lei Ling congratulates herself on having it all. When she isn't building up her ego, she describes her emotional state, proclaiming her love for flying and for Shanghai.

Only a small handful of text boxes are relevant to the situation she finds herself in.

This monologuing reminds me of female-focused fiction, where the emphasis is on relationships, emotions, and interpersonal drama. This may be a valid approach for slow-paced female-focused fiction, but Aero is a superhero comic. More precisely, a superhero comic from a brand that built its reputation on awesome action scenes, grand storylines and tough characters -- in other words, on male-oriented fiction. Fiction focused on events external to the character -- events which the character should be paying attention to instead of indulging in mental chatter.

Such extreme monologuing may have a place in introspective drama-focused comics. In superhero comics, all I see is an egocentric narcissist.

Chinatown of Anywhere, America

To Marvel's credit, they arranged Lei Ling's name correctly. As seen in this Quartz article, 'Lei' is her surname and 'Ling' her given name. As a bonus, her surname is the Chinese character for 'thunder'. I realize it's a low bar for praise, but I'm tired of Western authors making up Chinese-sounding names or placing the given name first or other such cultural faux pas.

But this is all the effort Marvel put into getting the cultural aspects right.

In English, Lei Ling's handle is 'Aero'. It may sound cool to an English-speaking audience, but Lei Ling is Chinese. When literally translated, 'Aero' in Chinese is the verb form of 'Fly'. It's a ridiculous name. To their credit, the Chinese translators rendered her handle as 'Cyclone' instead, a more fitting name.

This may sound like a petty complaint, but it ties into worldbuilding and immersion. Being Chinese and a resident of Shanghai, Lei Ling would speak Mandarin as her native language. When thinking of an alias for herself, it is far more likely that she will use Mandarin, not English. She'll use the alias 'Qi You' at home, and translate it to 'Cyclone' for English speakers. Or perhaps she'll refer to herself as 'Qi You' to Chinese speakers and 'Aero' to Westerners, claiming the latter sounds cooler. By using 'Aero' as her default handle, a Greek prefix whose closest Chinese cognate sounds absurd as a name, Marvel is pandering to an English-speaking audience instead of grounding Lei Ling firmly in her culture through her choice of alias.

At the level of worldbuilding and setting, the lack of attention to Chinese culture results in an inferior story. Superheroes are the epitome of Western (or even American) values. They are strong and powerful, work independently and (usually) with minimal government oversight, yet choose to use their powers to do good. They embody the Western ideal of the independent hyper-capable individual who nonetheless obeys a higher moral code to serve society.

Such values are alien to China.

Chinese culture emphasises social harmony, high power distance, rigid hierarchies, conformity, and etiquette. Someone who uses 'I' all the time the way Lei Ling does in her mental monologues will be seen as arrogant and ego-centric -- not an unfair assessment, given how little attention she pays to everyone around her. More importantly, individuals with superpowers in China will not be given the freedom of movement Lei Ling enjoys.

The West respects individual sovereignty. Governments rule by the consent of the governed, and the governed retain the power to dismiss the government -- or, if needed, overthrow it by force. An independent superhero operating freely in the West -- to be specific, the United States -- is believable because American culture respects the sovereignty of the individual. The American right to bear arms guarantees a citizen's freedom from tyranny; a superpower is a weapon a fortunate citizen carries with him at all times. These ideas were built up over centuries of history and proven repeatedly in the courts and on the battlefield. This assumption permeates all American superhero comics.

But these values are not Chinese values.

Political power grows from the barrel of a gun, Mao Zedong wrote, and the Chinese Communist Party controls the gun. Through absolute monopoly on legitimate violence, the government of China ensures the security of its regime. The Chinese government does not rule by the consent of the governed; it seized power through violent revolution and maintains power through control of organized violence. In a setting that allows for the existence of people with the power to destroy nations, you can bet such a government will want to maintain a stranglehold on power and justify it in the name of 'national security'. It cannot and will not allow a superhero to wander freely if that superhero is not a government agent, lest that superhero becomes a national security risk or supports 'separatists' and dissidents.

To be fair, China does have a cognate to superheroes in the wuxia and xianxia genres. However, stories set in those genres are based in an ancient, mythical China. A fractured land where government is weak and corrupt, bandits and monsters are everywhere, and there is a demand for heroes. It is sufficiently alien from modern China that the government sees little political threat in such stories. And yet, due to this alienness, the cultural values expressed in a wuxia genre do not apply to a story set in modern-day China. A wandering swordsman may be treated as a hero in a land where government is corrupt and weak, and evil is strong; he will be viewed much differently in a country where government is powerful and everywhere.

These cultural and political realities could have been fascinating to see. Perhaps Lei Ling is truly a government agent with a cover job as an architect,and she may be called up on missions for the government that conflict with her sense of justice. Perhaps she doesn't want to serve the Party to maintain her freedom, so she must keep an ultra-low profile, which conflicts with her desire to do good and be famous. Perhaps she is coerced into government service and sees her powers as a curse, yet feels compelled to help the innocent. Or maybe she willingly serves the government and sees no issues with politically-charged missions, making her an anti-heroine.

It goes without saying that in today's environment, writing about politics in comics may be a hot potato. Nonetheless, incorporating cultural values and social norms would add greater depth to the story. Lei Ling may have to balance her desire to be a superheroine with her duty to her family (to wit: get married and have children). She may have to handle lawsuits from ungrateful survivors of crises (not uncommon in China). She may face a legion of naysayers who think she's only a superheroine for the fame and fortune.

There could have been so much potential for personal drama and meaningful conflict. Instead of being a self-absorbed narcissist, Lei Ling could have had a more complex personality. Instead of already having it all, she has to struggle against her family, society and government. Instead of being a well-respected architect, she needs to deal with hordes of xiaoren -- 'petty people', troublemakers who obstruct her at every turn.

Not only that, the incorporation of local culture and values would further flesh out the setting. As is, we only know the city is Shanghai because Lei Ling says so. The story could be set in a Chinatown of Anywhere, America and nothing will change. There is nothing in the story that suggests that it is set in China, much less Shanghai.

Of course, had Marvel gone all the way in exploring Chinese culture in relation to superheroes, I suspect the government censors would blacklist Marvel forever. Even then, had Marvel relied on the politically-acceptable tropes of filial piety vs heroic duty, individual desire vs duty to society and other such conflicts, it would have reinforced the notion that the story is set in a living, breathing China instead of relying on Lei Ling's repeated assertions that she is presently in Shanghai.

Hot Air and Nothing More

Aero #1 has excellent art, but it's the only thing going for it. The storyline is nonexistent, the character is a narcissist, and there is practically no worldbuilding to speak of. It reads to me like a minimal-effort grab for Chinese yuan, focusing on style and completely ignoring substance.

Aero #1, by virtue of its art alone, is an improvement over modern comics' trend towards uglification. But art alone cannot save it.

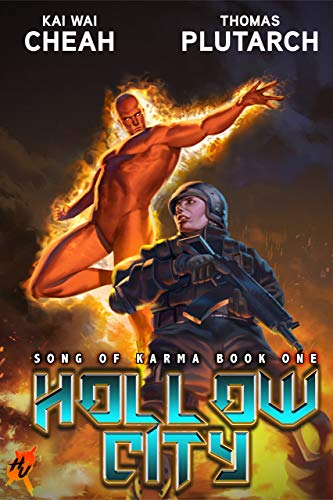

In my own stories, I pay extra attention to character and worldbuilding. If you want to see what a plausible portrayal of a Chinese superhero looks like, check out my superhero novel Hollow City.

Sup Dork?!? Enjoy the Upvote!!!