Science Communication – Why do we need it and why is it so difficult to achieve?

We live in strange times. Thanks to the internet now everyone can have a voice, and the spreading of fake news and pseudoknowledge seems to be at an all-time high; it is not that it wasn’t there before, it is that now we have the technology to make almost any message reach far and wide.

Combine this with the shrinking attention spans of the millennial generation (and those influenced by it) and questionable educational standards, and you get a perfect storm of unconfirmed, incorrect and misleading information being virally spread around – and more frighteningly, being assimilated by a portion of the population as a replacement for well-established scientific knowledge.

Suddenly we find ourselves having to convince people about basic scientific concepts that not only date from centuries back, but have proven themselves time and time again by serving as the foundation of a lot of our current progress.

The need for Science Communication – Why is it so important?

Democracy needs scientifically literate citizens that can discern what is legit and what is nonsense, in order to make better decisions that will benefit them in the long run. This is important both in an individual scale (in everyday situations, like not getting scammed by snake oil or miracle treatments), and as a population.

Also, since a vast amount of resources invested in science come from taxpayer money, the general public has the right to know what their money is being used for. Furthermore, in an ideal world, a scientifically aware population would be much better equipped to contribute in the evaluation of the progress being made (which would help keeping research institutions accountable), and also be more involved in the decision making regarding resource allocation into priority (or promising) endeavors.

Last week, as announced in this blog, I attended the N2 Joint Event, which included a series of talks, workshops and panel discussions about Science Communication.

The welcome lecture was held by Professor Dr. Johannes Vogel who, on top of being the possessor of one of the most amazing mustaches I have ever seen, serves as chair of the European Open Science Policy Platform and as chair of the European Citizen Science Association. He made some important points, which served as inspiration for my writing of this post.

What are some obstacles that need to be overcome in order to communicate science effectively?

Intellectual barriers.

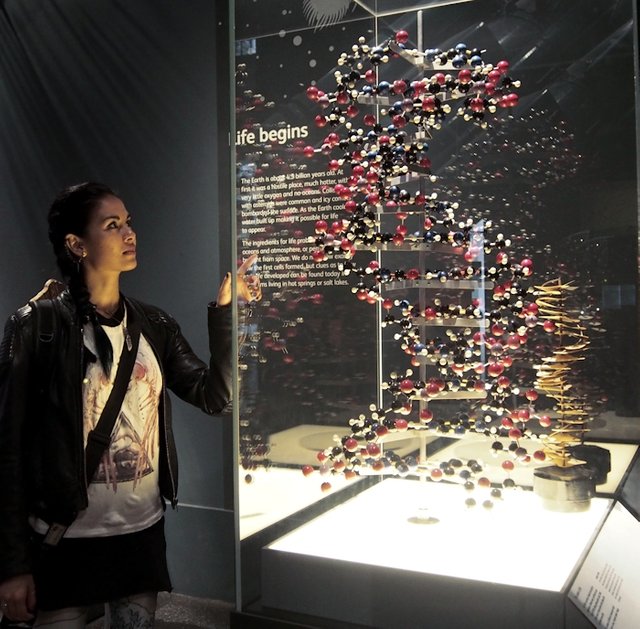

In his lecture, Prof. Vogel highlighted the fact that the Museum of Natural History (of which he is the director) is the most visited of all museums in Berlin, which reflects the fact that the general public has an avid interest in natural science. However, the information should be made accessible and presented in a way that is appealing, clear and easy to understand.

Many of us scientists are so used to discuss our topics with other specialists in our area that many times we forget that not everyone has the same conceptual background or grasp of concepts that we deem “well known” or fundamental. Therefore, trying to explain your science to an outsider becomes a challenge, more so if the outsider in question has a very basic (or sometimes inaccurate/erroneous) understanding of basic scientific principles.

We can even argue that it is not really their fault. Most of the times, the way Science is imparted in schools is dry, confusing and focused on memorizing of facts instead of understanding of processes and concepts. However, with a bit of creativity and enthusiasm on the part of the communicator, great results can be achieved.

The most impressive feat of science communication that I have ever witnessed was performed by Dr. Luis Herrera Estrella, one of the most prominent Mexican scientists, who was a pioneer in the development of genetically modified crops. As a teenager, I attended one of his talks aimed at informing the general public about GMOs. Within this audience, about 30% of them were farmers who were invited to learn more about the topic; these farmers were people with elementary school level of education, who learned how to read and write, do basic arithmetic and probably just some very basic notions about biology and plant reproduction (plus their empiric knowledge working with crops, of course). Still, by using a very simplified but precise language, a well-structured presentation that made the flow easy to follow, and analogies, he succeeded in communicating such a complex topic in a clear and impactful way (this was reflected by the questions the farmers were asking to him afterwards).

Presenting a simplified version of your topic that is understandable to almost anyone, while still addressing all the fundamentals of it, is a very difficult task. It requires a deep understanding of your topic and the ability to structure the intellectual components of it in a logical sequence that make them easy to grasp. That saying “you do not really understand something unless you can explain it to your grandmother” certainly holds a lot of truth to it.

Even further, truly effective science communication also requires a fine understanding of what aspect of the information being delivered would be of more value to the person listening, but that is a matter I will discuss in future posts.

Access barriers.

Even though most people probably have zero interest in reading scientific reports full of confusing graphs and specialized jargon, with the large majority of scientific papers being published in journals that charge for access, there is very little chance for the average, non-scientist person to be able to access the source material, even if they felt inclined to do so.

To make things worse, it is not only highly specialized information that gets stored in this pay-per-read manner. During the N2 Conference someone brought up how sometimes even material that is highly relevant not only for scientists but for the general public, is rendered pretty much inaccessible by a hefty purchase price.

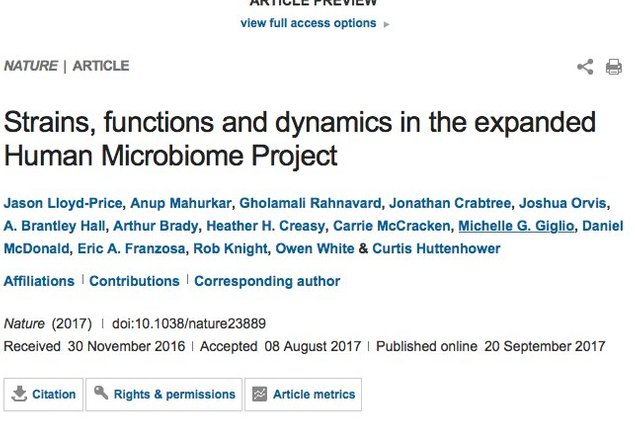

Take for example the freshly published results by the National Institute of Health (NIH) on the Human Microbiome project, which would deliver a wealth of information on human physiology, disease and health optimization for everyone.

If everything of relevance is behind a paywall, most citizens would be locked out of the opportunity to review this information on their own, and make better decisions based on it. Even within the scientific field, paywalls restrict access and slow down innovation by limiting access to the latest findings.

Flawed reward system.

In the current state of affairs, there is little to none monetary reward for researchers to do science communication. In our current system, science communication is something that you would have to do on top of your other obligations and responsibilities, and being an overworked, likely underpaid professional already struggling with getting results for your running project(s), science communication might sound like a nice but distant afterthought.

Even in the case of scientists who have assigned lectures as part of their contractual obligations, usually do it begrudgingly and view it as some major hassle that only takes away precious time from their research.

This brings us to an important subject for many of us doing science, which is: Why should I put time and effort into something I’m not getting paid for? There are very tangible benefits of communicating your science, of which I will write about in the next post. In other words, I will bring up some really good reasons why you should you bother explaining your science to the outside world outside of your lab/office, so stay tuned!

I never quite understood the pay-to-read attitude of most Science sites. Maybe Steem could help here? Something like upvote to read?

(Not the way it's done right now because it would need a bigger than 7 day payout period)

but that could work.

Ooh and excellent article btw

Science on Steemit? Based on the number of flat earth and anti vax people here it seems like a tough sell...

And whatever you do don't mention the commies.

What the earth isn't flat?????

I would like to point to http://sci-hub.io/ which is kind of like the piratebay of scientific journals.

Ooooh, and also, between academia.edu ad researchgate.net, many researchers publicly publish their articles within those networking platforms. That's first stop of call after checking Google Scholar.

Thanks I will check those links out!

But I would be happy to pay for a per-article read if I knew the money would go in the right hands.

You mean... to the researchers who actually wrote the articles?

Obviously no-one begrudges money also being invested into slick platforms allowing rapid and easy access, it just seems a bit excessive the typical per article rate. It's also pretty grim that so many institutions can't really afford decent subscriptions so scientists in poorer countries end up mostly depending on Google Scholar etc. I wonder as regards transparency of fund allocation of the larger repositories.

It has become a mafia that now mostly benefits a tiny portion of individuals, indeed.

The idea you propose is interesting, perhaps it could really work. In fact the other day @replichara was telling me about how he thought that the blockchain technology could be used as a way to keep science transparent, consistent and accessible. To our surprise, later we found that there are actually some public forums where people are connecting the dots and starting to propose ideas like this. So maybe we are into something!

Thanks for your comment, @julienbh!

There was a very famous article written in 1995 about how the internet would kill academic publishers. Academics would be able to post the results of their studies online, immediately, for people to read and review. That just hasn't happened.

https://www.scribd.com/document/292346391/Forbes-Elsevier-1995

I think a lot of it comes down to individual journals being seen as 'brands'. It is a big career boost to be published in a high-impact journal like Nature or Science- it could make a difference when applying for funding or research positions. Scientists need to publish in high impact journals in order to secure funding and get paid- rightly or wrongly.

There are some places where academics can publish online, for free (see f1000research and Gates Open Research), but until the reward system for academics shifts, content will remain locked away in high value journals.

This is, sadly, very true. I know people firsthand who, instead of publishing regularly in good journals, prefer to sit on 6-8 years of data in hopes to get it into Nature (for them, it's Nature or nothing!), meanwhile the graduate students or the postdocs who actually did most of the job have no publications to show for their hard work.

And the high impact journals know this, so they take advantage of it and don't care to improve their accessibility just because they know everyone is chasing after them anyway.

Thanks for such an interesting comment, @jonny1!

Its even worse in China, where universities actually have policies for handing out monetary awards for publication based on the impact factor of the journal the research is published in. Its part of the reason why fraudulent papers are a bigger problem in China than anywhere else. That's an extreme example but a similar system is in place in the West with improved job prospects the reward for chasing a high IF.

In my experience even lecture assignments do not really endorse communication (and do not represent a solution to the issue but rather an additional burden) due to being restricted to a not necessarily matching discipline and also entailing a whole lot of organizational responsibility.

In the potentially worst case people would have to design, teach and organize a lecture by themselves despite being employed as a researcher with a thematically different focus.

In this case, perhaps a solution could be to make these activities optional with an extra remuneration bonus for those who engage in them. That would incentivize people to see it more as part of their work instead of a burden, as well as giving them some return of investment for their efforts.

However, it also depends on the individual. I had some lectures taught by active researchers who were actually really eager to impart their subjects and had developed a very didactic approach to presenting their themes. They were always assigned the same subject every semester, so in theory they only had to prepare the course material once, and after that it was only required to make small updates as needed. So it would be a lot of work upfront, but not so much once you get the ball rolling.

Thanks for commenting, @galotta!

growing up i loved science. it was my absolute favorite subject.

but it turned on me, when i found tesla, i found we didn't always do what was best, but what was profitable.

i believe a change of perspective is needed about what we are doing on this planet, and our inter-relation with each other. realizing that your success does not mean my failure is a big step in the right direction. what needs to end is the idea of survival of the fittest.

but that idea is correct for another arena, science. survival of the fittest idea, the best idea, the best way to do anything. i don't think we actual do that, in all cases, especially when the best way isn't patent-able.

This is another problem, indeed. Most of the resources are not allocated evenly, but are distributed into limited "hot spots" of projects that are fashionable or attractive for funding sources (pharma, projects related to political agenda, or patentable technology).

Meanwhile, many other worthy projects are overlooked and under funded.

Thank you for sharing Great post Science Communication it's very Imprtant And can be better by providing a stronger understanding of current research, its trials, tribulations and, most importantly, its wider relevance to society. Relevance builds support and at a practical level such support leads to better funding. Knowingly or not, everyone in the country has a vested interest in the direction research moves in. Good science communication will make people aware of this. Resteem (y)

Well said, this is one of the most important parts of the message I wanted to convey. Thank you for your comment, @davinshi

The Internet has changed all the joints of life, the flow of information so smoothly, many are positive, not least a very negative.

About the communication is also easier with the Internet network also has an impact on both sides, freedom of speech is implemented with straightforward today, on the other anarchy news, blasphemy and insults are also more easily delivered in the form of hoax and others.

And the point is, like every other life session, all technological progress remains like two sides of the coin, just how we look at it.

Hi there. I enjoyed this article. Are you implicitly suggesting that Steemit may offer a sufficient reward system for scientists to share their research with a general public in a digestible format? As the same thoughts have passed my own mind.

Funnily enough, one of the speakers at the Science Communication conference I attended said "You cannot make a living out of being a science blogger". And of course, I was like...

Nah, but seriously, I don' think Steemit by itself would be sufficient as a reward system for scientists who want to do science communication. While it certainly brings a really good return of investment for the content shared, I am mostly worried about the reach since this is still a "niche" community and mass adoption is still a goal to achieve.

I tried to recruit some scientists by preaching the Steemit gospel to them, even showing them the payouts that my science posts usually get, but even though some of them seemed really interested, not one of them has followed through so far. So there is a resistance that has to be overcome somehow (is it the "crypto" side that makes people distrustful? I don't know).

I'll have to admit it seems quite attractive to me. I really feel nauseous at the cut-throat competitiveness I see within academia, I also prefer if possible the idea of being autonomous and my own boss instead of agreeing to spend a certain amount of my year being tied to a certain job and place, but I do love researching about cool stuff, so science blogging could be an interesting avenue at least for a while. Good point about the current reach - however if you build your audience now you'll be a step ahead of the rest if Steemit baloons in popularity.

By the way, I'm really impressed that with 659 followers you are getting the pay-outs on your posts that you are getting!

Getting consistently high payouts is a recent thing, though. If you look at my posts before I published the anti-vaccine article debunking, it was more of a hit-and-miss situation back then, with some post making a good 20-40 bucks, while some others would make only a couple of dollars (or sometimes not even that).

The science community is very supportive, though, and I was also fortunate to engage early on with some more influential users through commenting on their articles or participating in their challenges.

Yes I really like the "sub-community" that seems to gravitate around the science tag!

Interesting to hear about the evolution of your success on here. Thanks for sharing!

That's follower quality over quantity, haha!

Science publishing sure seems like a bewildering scam, doesn't it? Scientists submit their papers for free, peer-reviewers judge and edit them for free, everyone contributes to these projects like they're participating in some wonderful altruistic enterprise. And then Elsevier turns around and sells subscriptions for prices that only wealthy individuals or institutions can afford.

Indeed! I often wonder how on Earth did this deal come to be... good thing is that there is already some strong resistance to this ridiculous model, like the battle here in Germany against Elsevier:

https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/german-universities-plan-life-without-elsevier

So it's good to see that even people in the high spheres realize that this is a ridiculous situation that needs to stop. Thanks for your comment, @winstonalden!

That's good to hear! I hope there's some change. The people who run this racket are not going to let it go without a fight!

Science communication is so very important and it needs to be communicated in a simple way understandable to all...

Good post..

Thanks for letting us know!