Relative Realities Pt 2: The Two Paradigms

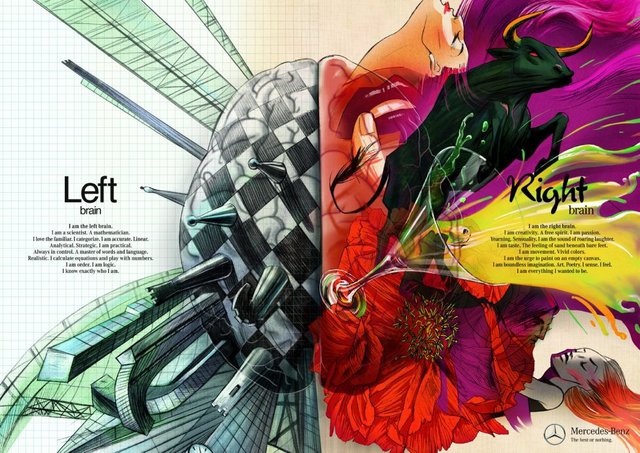

The last chapter provided something of a scientific groundwork or basis for what’s to come. Now, I know, quantum physics is a highly disputatious field marred with intellectual controversy, but this controversy gives us just enough wiggle room to reimagine things a bit. You see, in addition to it being the most sophisticated interpretation of the universe we can mathematically describe, quantum physics stretches the boundaries of what we allow ourselves to believe is “real” or even possible, making it the perfect place to start when it comes to redesigning our most basic paradigms of life.

The particular paradigm that begs to be stretched is the materialist model. You see, most of us, consciously or otherwise, assume this universe is a material structure or mechanism. For convenience sake, I’ll use the words mechanistic, materialistic, and occasionally objective interchangeably when describing this model.

So, in this machine, we each rather miraculously spring into existence, have seemingly intense and meaningful experiences, including and mainly consisting of no shortage of suffering, only to invariably (and rather anticlimactically) vanish. Furthermore, since our reality is basically a machine, all events and outcomes can be predicted, and are in fact, an inevitable consequence of the universe’s moving parts. This viewpoint is called determinism. In this model, our lives, all our experiences, fears, joys, relationships, beliefs and livelihoods are nothing more than a brief, meaningless flash in the pan in the grand scheme of the universe, whose actions are driven forth from the past inexorably into the future, with no choice or free will involved.

The justification for this model is predicated on another assumption; the world is composed of solid ‘stuff’ called matter. Therefore, our conscious minds are nothing more than a fleeting, epiphenomenal offshoot of the arrangement of that matter, slated to be destroyed the moment said ‘stuff’ gets rearranged.

In this model, consciousness is something of a fluke, and we’re the unfortunate, unhappy byproducts of that fluke. Our jobs then, as finite, intelligent beings, is to impose our will upon this stupid, inert universe to extract some semblance of order from it, because not only does the cold, unfeeling universe not give a damn about us, but it couldn’t even if it wanted to. (Because it’s just too stupid.)

And that’s looking at it optimistically.

Frequently people use this worldview as a sort of ‘nothing-buttery’ about life. By denigrating their existence to ‘nothing but’ the fluctuating of matter, one can easily justify one’s own inertia, bitterness, and cruelty, under the pretense that human existence, and consciousness itself is void of any objective worth. Without any overarching ethic to guide them, (take for example the presumption that human existence is indeed valuable) the temptation for humans to tilt towards unseemly behavior is almost overwhelming. If one)succumbs to that temptation, one now has free license to sign over any individual responsibility, cling blindly to totalitarian ideologies, act in ways that would ordinarily defy human conscience (perhaps even their own), or rarely even act at all, excepting to occasionally indulge in the fulfillment of their own short-sighted, selfish cravings.

This attitude strips one of any moral obligation contribute anything of value to humanity, or to make efforts to be responsible, ethical or competent in any way. And so those who already tilt towards cynicism and sloth find it particularly rewarding. The effects of these motivations are more than mere speculation, though. Look no further than the events of the last century for evidence of such an attitude taken to its extreme.

However, supposing the results of the double slit experiment are accurate, and furthermore, that our interpretation of those results are accurate, it, and other strange discrepancies in the materialist paradigm could serve as the basis for an entirely different model of reality; one in which matter is no longer the primary component of existence, but experience is.

I’ll call this model the experiential model, but I’ll also refer to it as a living, subjective, or intelligent model of the universe too.

From this perspective, consciousness isn’t some random, unfortunate fluke brought on by an incomprehensible sequence of lotteries landing us where we are today, instead, it’s truly integral to reality itself. Intelligence in this model is seen as the ‘point’ of existence, rather than a meaningless byproduct. In this model, our actions aren’t generated by a random sequence of events, but a result of our own autonomy, and as such, we have the freedom to choose between greater or lesser suffering in our lives, both for ourselves, and those around us. This freedom of choice is the basis for what we call morality.

Now, the experiential model isn’t exactly a new one. Rather, it’s about as old as history itself. Mankind has been operating on the grounds of a moralistic, intelligent universe for about as long as we’ve been able to think. It’s guided our thoughts, actions and perceptions for millennia. One key feature of this perspective however, was that it seemed incapable of divorcing the idea of an intelligent universe from the idea of a human, paternal figure (or figures) to ‘embody’ that intelligence. In the doctrines, the cosmic grandfather both created and governed the universe, watching lovingly yet sternly upon all that we thought, said and did. This provided our lives with much-needed structure and meaning, giving some justification to the harsh, apparently arbitrary punishments of life.

However, envisioning the universe in this way came with its share of drawbacks. For one, this deity seemed to err rather unreasonably on the harsh side with his judgments, often acting from cruelty, jealousy, and outright malice. Furthermore, his punishments were inconsistent. He seemed to penalize some people for certain misdeeds and ignore the same actions in others altogether. Then there were the many disagreements over what this being expected, how to please him, and who or what he even was, taking place not only between cultures, but within them as well. This all gelled together nicely with the fact that in show of allegiance to him, people would go to unthinkable lengths, and inflict unimaginable pain and suffering upon each other, the world, and themselves, hoping to curry his favor.

It appears that after a few millennia, all this judgment, compulsion and guilt got far too oppressive, (and frankly embarrassing) for some people to handle, and a growing number of individuals decided to dispense with the divine grandpa, and the intelligent model of the universe altogether. However, shedding the uncomfortable, overbearing dictator created its own form of discomfort. Instead of feeling enslaved and oppressed, people began to feel a sense of aimlessness and existential dread. If that didn’t explain how the universe works, what would?

Cue the scientific revolution.

In the late 18th century (the last mere moments of human history) the rapid advancements of science and technology fueled a newer, more sophisticated interpretation of the universe to trounce over the previous one. And trounce it did. Axiomatically, the two models could not coexist, and at the time, a lack of empirical support for the former caused it to (mostly) collapse in the face of greater understanding. The philosopher Nietzsche decoded this event with three of the most memorable words of the nineteenth century.

“God is dead.”

Contrary to popular belief, to him, this was far from a triumph. In fact, as far as he was concerned, it was perhaps the darkest moment in human history. Without the guiding support of religious belief, he feared humanity might wander horribly astray. Stripped of any cosmic or divine significance, he predicted we would abandon morality, and our lives would degenerate into malevolence and barbarism.

Say what you will of religious dogma, it did provide some basis for ethical conduct. The same can’t quite be said of scientific thought. At least not yet.

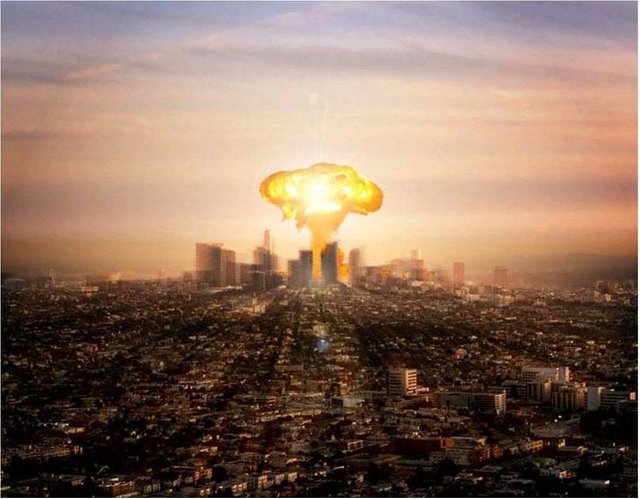

So, with the ethical structure of our society all but defeated, the events of the 20th century left mankind teetering dangerously close to the edge. Horrors from secular, totalitarian dictatorships ensued, generating suffering, catastrophe and death on an almost unimaginable scale, and in the next few decades we emerged with all the power, resentment and technology to annihilate this planet, and no real reason not to.

And who could blame them? Life is extraordinarily difficult, seemingly as much so as it possibly could be, and with science demystifying the origins of human existence, and indeed, existence itself, almost by the day, rational, hardheaded people had every reason to smash the big red button, and send their enemies straight into oblivion.

And yet, here we are, still very much alive, as humanity eked out a win against nihilism when the stakes were at their peak. And how, you might ask? It seems that for all our tough talk about objectivity and rationalism, our commitment to a subjective, intelligent model of the universe, at least for the moment, prevailed.

Next time, we'll go over the proposition of nihilism, and why in our current model, it's still a perfectly reasonable conclusion to draw, and furthermore, why we haven't drawn it.