UN-LEARNING M I N D L E S S N E S S - NeuroScience and the Art of Meditation

Language is difficult. Once concepts have manifested themselves, they are no longer analysed in depth, but accepted as given and often perceived purely from their superficiality.

Photo by Honey Kochphon Onshawee auf Pixabay

Something seems to have been lost in the translation of

the meaning of mindfulness:

That it's not about achieving a special mastery of something particular, not even about becoming something special at all. In the Buddhist tradition and its different schools, the idea is universal that meditation is not a means of "getting" or "becoming something". It's not about achieving some kind of superiority, it's not a holy grail and it's not a strategy for daily life. It has nothing to do with all this. It's more of an "un-strategy". It has no ultimate goal, it is just as interested in unlearning mindlessness as it is interested in being "not interested", like in the philosophy of WuWei/skillful spontaneity. It does not want to be determined, but at the same time it uses discipline to decisively reach an undecided state that people can have every second. But there is noThing to "have" and there is also noThing to "be".

As it seems, every ordinary interpersonal contact and action, every scientific approach that has not gone through the process of unlearning mindlessness, or is not going through it continuously, can be seen as accompanied by what here in this text is later on called "Default Mode Network".

If mindfulness were a subject, and one would say that with the usage of this subject, let's call it "factorin", a scientific experiment can begin to function in this sense in a mindful way. Without factorin something different comes out than with factorin.

The scientific question now could be: What could be different, what could be the otherness of it?

But mindfulness is not a means to an end and in Buddhist teaching it is also nothing that a (devoted) ordinary person should ever stop doing, because he is continuously integrated into contexts and has daily experiences that constantly challenge him to react to the world and to himself. Life is a process that promotes certain habits and weakens others, moments of clarity are replaced by moments of adeptness, it is a matter of a person becoming a practiced meditator not to fully practice the habit of mindlessness.

In other words, practicing meditators achieve different results in their world perception and reactions to the world and their fellow human beings as non-practicing people. The Buddhists themselves are the first to admit that non-meditators can also have phenomenal experiences similar to those of meditators without ever practicing a meditation in the recommended form.

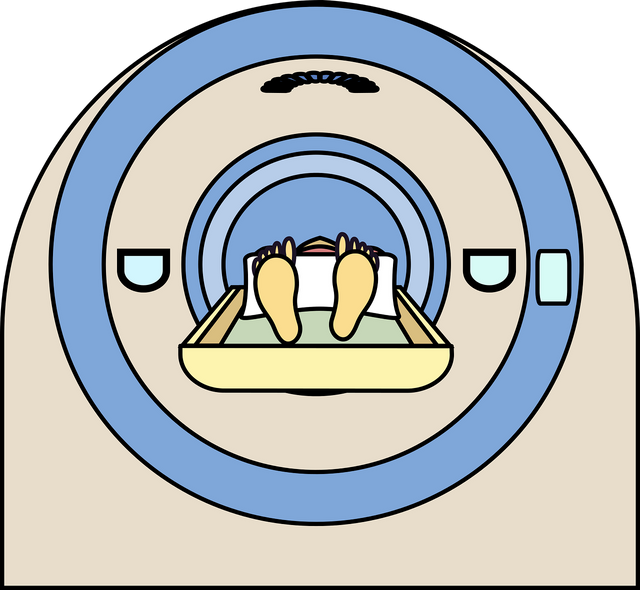

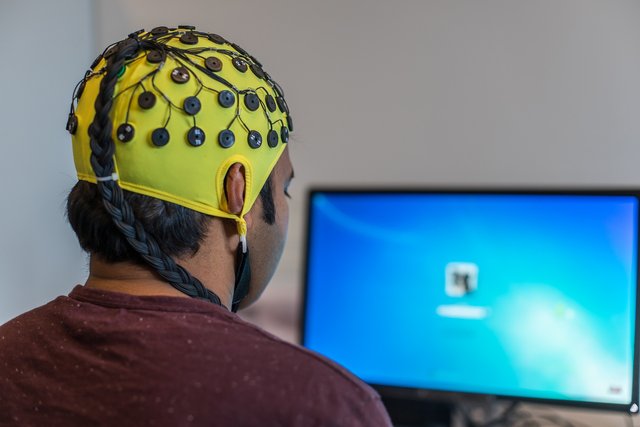

In this article, I link to some scientific studies resp. refer to the sources. The so far used measurement instruments to do research in the cognition sciences and studies related to meditation are:

- fMRI devices

- EEG devices

Meditation has been the subject of scientific research for about the past 40 years but only started to gain popularity in the late 1990s ... . The neuroscientific study of meditation has involved both fundamental and clinical research and aims at understanding how mental training affects the brain, the body, and overall health.

source

I want to emphasize that the research in this field is still in it's infancy and we are not presented with hard scientific evidence which undoubtedly proves what is so far speculated or indicated. But the already collected results are nevertheless intriguing.

Though personally, I doubt that it ever will be possible to investigate something immaterial like "consciousness" or "free will" on a quantifiable level to a truly accurate state.

In the past decade, 21 studies have investigated alterations in brain morphometry related to mindfulness meditation. These studies varied in regard to the exact mindfulness meditation tradition under investigation, and multiple measurements have been used to investigate effects on both grey and white matter. Studies have captured cortical thickness, grey-matter volume and/or density, fractional anisotropy and axial and radial diffusivity. These studies have also used different research designs. Most have made cross-sectional comparisons between experienced meditators and controls; however, a few recent studies have investigated longitudinal changes in novice practitioners. Some further studies have investigated correlations between brain changes and other variables related to mindfulness practice, such as stress reduction, emotion regulation or increased well-being. Most studies include small sample sizes of between 10 and 34 subjects per group.

excerpt from above source

But first let's get started with an observation.

Every human has a basic feeling of "I",

one feels existence as temporal. Practicing meditation is also about the fact that this sense of "I" becomes dissolved, that an "I" does not really exist. Why is this intended and helpful at all?

Try to sit still with yourself in am empty room for half an hour and stay comfortable and calm. No stimuli, no distraction from other people. You will find that you cannot do it if you are not a practiced meditator. You get restless, nervous and even anxious to escape the situation. It's suggested that this is a sign of stress. The assumption is that if we are stressed while not having something to distract us this can be seen as an unhealthy lifestyle which causes all kinds of illnesses and psychological problems.

If you have ever had the reverse experience that you had an experiential waking under the influence of psychotropic substances such as magic mushrooms (psylocybin or similar), then this was tied to the fact that you had lost the sense of I as well as the sense of temporal processes and you felt connected to everything.

Once, under the influence of Psylocybin,

pixabay/

I had the strange experience of temporal absurdity: I lost control of my body and fell almost straight to the ground. During the fall I could see very clearly that I was falling, because it happened very slowly, so it was possible to be observed. But I did not feel the impact on the ground, it was completely indifferent that I hurt myself. It wasn't "me" that hurt itself, it was just an event that had little to do with me, because there was no "me", "mine" or "I". There was a general cheerfulness and hurting the feelings of those around me, a thing of impossibility. Where there is no "I", nothing can jeopardize an identity. Being awake in this way without identity is probably the strangest experience I have ever lived.

Now I am not arguing that psycho-substances should be used as such a means of experience. On the contrary, if you only use it as superficial fun, it may well be that the always after the next buzz addicted mind wants to abuse it. I for my part was not eager to repeat this strange experience, at that time I was undecided what I should do with it at all. The inexplicability of such an experience quickly makes one look as if one has lost one's mind, and although it is true that losing the mind comes very close to what I mean by losing mindlessness, it can be completely misunderstood.

Asking: "What am I or who am I or where am I" produces only ongoing answers that want to link to a destination or identity. So it would be better to ask:

"When am I?

Is there an answer? Hardly, because the only answer would be that I am right now.

But the mind is hard at work constantly producing additive thoughts that only aim to keep the "I" and bind it to a locality and identity. The mental activity is so strong and constant that, if you listen more closely, you merely constitute a perpetual stream of thoughts and internal chatter.

In neuroscience, this (modulative) "brain network" is referred to as the Default Mode Network/DMN. In Buddhism it is called Citta

DMW: see page 1917 in this link

Citta: "For a long time this citta has been defiled by attachment, hatred, and delusion. By defilement of citta, beings are defiled; by purity of citta, beings are purified"

If one were to set up a mental box that would collect everything that concerns "I" and another box that would collect everything that is "not I thought", the box would become full of "I things" and the other box would remain completely empty.

The aim of meditative practice is to reduce this chatter. Not by forbidding it to yourself, not by punishing yourself for it. The chatter wants to be observed and as soon as it is labelled as "existent" (like "there is anger"), one does not try to defend oneself against this enemy, but accepts a thought merely as "present", one integrates it as a friend who can simply make himself comfortable and become quiet. Since the thoughts come from somewhere like racing and we get to deal with them every second, meditation means that with the appearance of a thought, it is integrated just as quickly, so that the focus can stay on the meditation object (for example the breath).

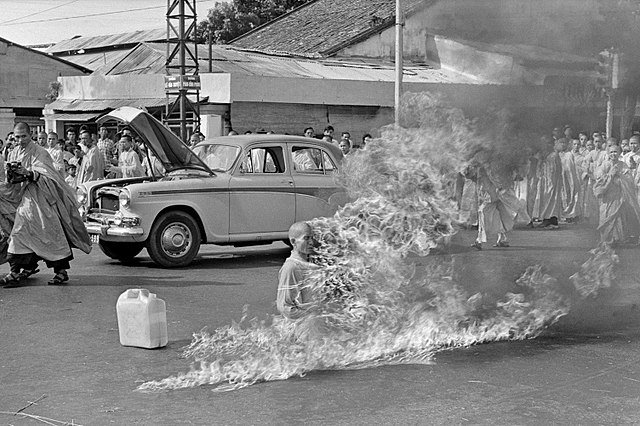

For the purpose of the argument, I will now illustrate the otherness of practiced meditators by means of a particularly extreme example.

By Malcolm Browne for the Associated Press - Immediate source/Public Domain

The monk Thích Quảng Đức became world famous because he burned himself. Self-immolations among Buddhists are not as rare as one might think. But the remarkable thing about the action of Thích Quảng Đức is that in the ten minutes that his body was consumed by the fire, he remained seated in the meditative position, did not make a sound and showed no instinctive impulse of self-preservation. He died after these minutes without any sign of agony, his body simply tilted backwards. Such an act of will may also contradict the theory of the non-existence of free will. I don't want to politically discuss the case further, I intend to focus on human experience. If humans, like the monk, and by the way also other humans, who are exposed to extreme physical experiences, are able to switch off the pain receptors of their physis (losing the sense of "I"), my assumption is that such a different kind of experiential space is a result of mindfulness and has to be examined more closely. Therefore, the experience of self must not be eliminated from the sciences; and consciousness must not be evaluated as insignificant from the cognitive sciences. Now it seems the monk has attained the absence of self and at the same time he had been present as long as the body had the task of remaining motionless. As not to appear crazy. For if consciousness had "given up" the body, so conscious control over the body would no longer have taken place, the body would have followed its instincts and - like a headless chicken - would have run or thrown itself around. This raises the question of how a person can simultaneously give up his self without at the same time giving up control of physical movements and pain expressions. Or it looks as if the surrender of the physical self has taken place before the surrender of the mental self. Which again seems conclusive when one considers that Buddhists still give their dead time and that death is really only considered final when signs of death can be seen on the human body, such as rigor mortis or death spots. This contradicts modern medicine, which established cardiac death and later brain death. After the boundary between life and death is drawn there where no measurable brain waves are displayed. The fact that humans could not be completely dead nevertheless, is generally not doubted in modern medicine. But when there is this difference in people regarding their state of having unlearned mindlessness than it seems logical that there is also a difference in consciousness. The difference in individual conscious experience happens through sensory perception, seeing, smelling, tasting, feeling and thinking (which Buddhists also regard as a sense, the "mind-sense"). as it is pointed out in the book The embodied Mind, written by Francisco J. Varela, Evan Thompson and Eleanor Rösch in the year 1991 (Page 56). I never have thought about this difference in every day language and encounters. When I talk to people about "our consciousness" I talk in a way that somewhere in the background there is lingering a unity. Because, as humans, we indeed all are conscious about our selves. But does this anything say about the quality of it? Obviously not. Even in one's own consciousness unity can be questioned: We typically suppose that consciousness unifies and grounds all the disparate elements of one's self -one's thoughts, feelings, perceptions, etc. The phrase "unity of consciousness" refers to the idea that one understands all of one's experiences as happening to a single self. As (Ray) Jackendoff rightly notes, however, there is an equally obvious disunity in consciousness, for the forms in which we can be consciously aware depend considerably on the modalities of experience. Thus visual conscious awareness is markedly distinct from auditory awareness, and both are markedly distinct from tactile awareness. Since, as we have just seen, Jackendoff's computational theory is constrained by phenomenological distinctions, he must give some account of this experiential disunity. Jackendoff suggests that each form of conscious awareness is derived or projected from a different set of representational structures in the computational mind: The hypothesis that emerges from these considerations is that each modality of awareness comes from a different level or set of levels of representation. The disunity of awareness thus arises from the fact that each of the relevant levels involves its own special repertoire of distinctions. . . .The presence of a sense of self can help explain the absence of a sense of self.

Than we can no longer assume that people have a unified consciousness but a un-unified one,

[This theory] goes against the grain of the prevailing approaches to consciousness, which start with the premise that consciousness is unified and then try to locate a unique source for it. [This theory] claims that consciousness is fundamentally not unified and that one should seek multiple sources.

source

pixabay

Shopping in the Ego-Center

You know this: Entering the parking lot and being mad about all the other vehicles littering the space chaotically.

What's common between educated Westerners is that we easily think of others as the selfish egocentric mindless people while we ourselves attained already a certain kind of sensibility if not wisdom.

We associate "cognition" as the better asset - in absence of being able to explain the hard problems of science - and dismiss "consciousness" as the lesser one. Because, humankind appears as stupid as it ever appeared and "we" do not learn from history. Therefor, it seems, the logic dictates that it would probably be better to get rid of consciousness and let cognition dominate the scene. But what actually had happened is that we projected the judgement of egoism onto the world (the stupid others), underneath including ourselves as being stupid but didn't want to admit it.

We shopp all kinds of things and toys from the shelves like: "I am a social phobic", "I am a good kid", "I am a brilliant speaker", "I have a bad habit", "I have a good character" etc. etc. - same we do with the other objects in the shelves, meanly: people close and far.

It must be remembered that Jackendoff attends to conscious experience because he holds that it results from an underlying computational organization. Thus for Jackendoff the distinctions present in the phenomenological mind are not made by the phenomenological mind; they are, rather, projected into the phenomenological mind by the computational mind. Indeed, Jackendoff explicitly rejects the idea that consciousness has any causal efficacy; instead he holds that all causality takes place at the computational level. He is thus led to embrace a consequence that he himself admits to be unpleasant: if consciousness has no causal efficacy, then it can have no effects and so "is not good for anything".

source

Actually, this notion is quite seductive and I sometimes think that "too much awareness" might somehow be a mistake in human evolution. But no. Let's be fair to ourselves. Only because human experience lacks objective data we should not go for the assumption that it does not provide us with something other than what we see. The gab between science and human experience should not despair us but only indicate that we haven't investigated enough and that bridges can be built. Some bridge builders are working on this problem.

Maybe scientists who are meditators themselves started to work on bridges for the reason that:

"Buddhism is not telling anyone that he should believe that he has a self or that he does not have a self. It is saying that when one looks at the way one suffers and the way one thinks and responds emotionally to life, it is as if one believed there were a self that was lasting, single and independent and yet on closer analysis no such self can be found. In other words, the aggregates (skandhas) are empty of a self." (Tsultrim Gyamtso)

An examination of experience with mindfulness/awareness reveals that one's experience is discontinuous - a moment of consciousness arises, appears to dwell for an instant, and then vanishes, to be replaced by the next moment.

But the overall picture of mind not as a unified, homogenous entity, nor even as a collection of entities, but rather as a disunified, heterogenous collection of networks of processes seems not only attractive but also strongly resonant with the experience accumulated in all the fields of cognitive science.

source

Through the visualization of fMRI technology,

scientists can make visible what is going on in the human brain when it is exclusively occupied with chattering or when it has integrated the chattering and become quiet.

Although mindfulness tends to strengthen the "self" (in contrast to the ego) and to decrease judgement, it seems that in the context of these different aspects above all the flexible and differentiated handling as well as the recognition of the respective mode (and the possibility of "jumping back and forth") are trained (Farb et al., 2007; Ott, 2010). It also fits in with this autoregulatory approach that the midline Default Mode or Resting State Network, which is associated with "leisure" and inner contemplation (also with stress resilience, dementia prophylaxis etc.), but also with self-referential "daydreaming", is modulated by meditation (Lazar, 2011; McAvoy et al. , 2008; Ott, 2010; Pizoli et al. , 2011; Schnabel, 2010).

source/translated

The different results in the control groups, on the one hand experienced meditators and novices or inexperienced meditators speak at least insofar as it has been found that experienced meditators seem to operate much less in the Default Mode Network than inexperienced meditators.

The DMN in which the proband reacts in an unfocused, unobservant, preoccupied and jumpy manner. The thoughts rule the mind unfiltered and disorderly. The lack of concentration on a meditation object and the associated inability not to react impulsively to stimuli favour the DMN. In contrast, what is achieved through meditative mindfulness is in some places called the "Control and Tasking Network".

However, there is no need to think that DMN is something "bad", because in fact this somewhat misleading term can be understood as a state of pause, when no task is given to the human brain. One lets the thoughts wander, one has daydreams as far as nothing else requires the attention. Now it is however in such a way that daydreams and the wandering thoughts is a nevertheless quite broadly conceived term and has room for interpretation.

The Buddhist tradition of meditating here holds a quite clear view: That such a "pause state" does not need to be understood as "relaxed" at all if the process of thinking does not follow a certain order and is even experienced as stressful, as, for example, when rolling back and forth at night. Buddhists assume that every person has a rather untrained mind and that if the brain muscle is not trained, the thoughts jump aimlessly and like uninvited guests sometimes here and sometimes there. But there is no such thing as complete thoughtlessness in ordinary people, even the advanced practitioners do not state that they are empty of thoughts. This state is rather one of pure enlightenment and is achieved once Nirvana is entered.

By precise, disciplined mindfulness to every moment, one can interrupt the chain of automatic conditioning - one can not automatically go from craving to grasping and all the rest. Interruption of habitual patterns results in further mindful- ness, eventually allowing the practitioner to relax into more open possibilities in awareness and to develop insight into the arising and subsiding of experienced phenomena. That is why mindfulness is the foundational gesture of all the Buddhist traditions.

Strictly speaking, though, karma is the very process of intention (volitional action) itself, the main condition in the accumulation of conditioned human experience.

Quotes from "The embodied Mind".

The Wiki-entry under "DMN" sais:

The default mode network (DMN) may be modulated by the following interventions and processes:

Acupuncture

Meditation

Resting wakefulness

Onset of sleep

Stage N2 of NREM sleep

Stage N3 of NREM sleep

REM sleep

Sleep deprivation

Psychedelic drugs

Deep brain stimulation

Psychotherapy

Antidepressants

What has so far been admired about people, namely their ability to be on autopilot, has a downside. This autopilot makes it possible for us to do manual things such as driving, showering, brushing teeth, cooking and running, but at the same time think of everything possible and impossible that has nothing to do with the momentary situation. Now the Buddhists say: "But it should."

Why?

Why should we take time and discipline in becoming meditators?

From the point of view of human curiosity and the desire to improve oneself or to live healthier, we are pursuing this urge to investigate. This does not necessarily correspond to Buddhist philosophy, according to which it is not necessary to live healthier and longer in order to balance an egoistic advantage or an egoistic sense of deficiency. Nor is it a matter of fulfilling a long-held desire to be more effective at work and in private life, nor of becoming rich in material wealth.

From the Buddhist point of view, it is better to be healthier and live longer so that others do not have to experience grief with us. Health and well-being are needed in the system as such. The less unhealthy and unwell people live in a system, the less the system as a whole suffers. Buddhists are therefore primarily concerned with reducing suffering. And the highest level of their teaching is about dissolving suffering. This can only be achieved by experiencing the "I" as an illusion.

Our apparently normal state of mind (mental chatter) is widespread. The self-test (an empty room without other people and stimuli) is very easy.

The motivation to want to live with a hundred present people rather than with a hundred absent minded people is quite high, isn't it?

Scientific research as well as Buddhist meditation practitioners say: Yes, through constant training you achieve a generally more equanimous state of being. The researchers say: The brain is like a muscle that needs to be trained and it is likely - at least this is what the previous studies suggest - that a trained brain has the nice side effect that a person stays active longer, suffers less from mental destructive states and also becomes more concentrated and effective in his activities. The concept of plasticity has already established itself in general usage.

Buddhists do not need such seductive side-effect arguments, as they actually benefit from the beautiful side-effect themselves, but do not see it as their ultimate goal. Which one can at least find very sympathetic, because they obviously don't want to seize world domination, but would probably be quite satisfied if their kind of existentialism was widespread. They are, so to speak, a portable religion that has made it to the present day.

DMN modulating seems taking place through active meditation and constant repetition. One thus replaces the bad habit (unguided and reckless mental chatter) with a good habit (directed meditation).

Let's be honest: wanting to take psycho-substances every day in order to reach an I-less state would only be like the cat chasing her own tail again. A good thing, though, is:

Endogenous "drugs": Our body is responsible for the release of such substances.

In any case, a participation of central limbic and mesolimbic or mesostriatal mechanisms is to be assumed, i.e. the brain's own motivation and reward systems - with dopamine as the leading messenger substance - are involved (overviews among others Esch & Stefano, 2004; Esch, Guarna, Bianchi, Zhu & Stefano, 2004). So it is not surprising that dopamine could be directly detected in the context of meditation, both in the brain and in plasma (e.g. Jung et al. , 2010 ; Kjaer et al. , 2002). There is also an involvement of enzymes for the production of noradrenalin (NA) and adrenalin (A) and thus a direct relation to stress physiology (and modulation of stress at the molecular level) is established (e.g. Jung et al. , 2012).

If you are interested in the details of the biochemical releases and also the applications already used in medicine, read those scientific papers attached below.

In fact, we face so drastic changes with artificial intelligence applications

that sensibility and sensitivity is going to be needed much more than ever, if you ask me. Also indicated in my last article WHEN THE BOOK READS YOU WHILE YOU THINK YOU READ THE BOOK.

To thicken the brains matter through implanting a computer chip into our brains: I doubt it'll do the same. But then, if there is nothing to avoid this kinds of developments, than I plead for educating people and oneself in becoming a meditator in order to operate in an empathic loving way to be of service to others.

Meditation is not a sole bringer of salvation. Someone who is up to no good can be an excellent meditator, a sniper killer. But first the turn to loving kindness and the desire that others may prosper, those who are close to me, those who live a little further away from me, and also those I do not like. Not only people, but all living beings.

The right attitude is therefore the alliance with meditation, without which it remains merely a technique. But in ending a meditation where we thought of someone with loving care and wished him wellbeing, it is difficult to immediately become angry again or to suffer. Such meditation is preserved, like the fragrance of a perfume where the bottle has already been closed and yet has an effect beyond that.

“Of immateriality,” said Imlac, “our ideas are negative, and therefore obscure. Immateriality seems to imply a natural power of perpetual duration as a consequence of exemption from all causes of decay: whatever perishes is destroyed by the solution of its contexture and separation of its parts; nor can we conceive how that which has no parts, and therefore admits no solution, can be naturally corrupted or impaired.”

“I know not,” said Rasselas, “how to conceive anything without extension: what is extended must have parts, and you allow that whatever has parts may be destroyed.”

“Consider your own conceptions,” replied Imlac, “and the difficulty will be less. You will find substance without extension. An ideal form is no less real than material bulk; yet an ideal form has no extension. It is no less certain, when you think on a pyramid, that your mind possesses the idea of a pyramid, than that the pyramid itself is standing. What space does the idea of a pyramid occupy more than the idea of a grain of corn? or how can either idea suffer laceration? As is the effect, such is the cause; as thought, such is the power that thinks, a power impassive and indiscerptible.”

Imlac Discourses on the Nature of the Soul.

Text sources & links:

Cortical Thickness and Pain Sensitivity in Zen Meditators: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/d4e0/e0e87d83d841d7fcebfbf9d10cdc42648697.pdf

The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation

Article in Nature Reviews Neuroscience · March 2015

Wuwei and Flow: Comparative Reflections on Spirituality, Transcendence, and Skill in the Zhuangzi

The embodied Mind - by Francisco J. Varela, Evan Thompson and Eleanor Rösch

Source/German / Die neuronale Basis von Meditation und Achtsamkeit

Tobias Esch

Wiki-entry default mode network (DMN)

The effect of meditation on brain structure: cortical thickness mapping and diffusion tensor imaging

Wu-wei and Wu-zhi in Daodejing: An Ancient Chinese Epistemological View on Learning

I upvoted this earlier, in support, but did not read. It's been one of those weeks. Up and down. Playing with collages again. This time took stronger measures so I hope everything will be up, up, up.

So here I am, fit to read your very thoughtful blog, which deals with weighty concepts. I'm not sure I can do the blog justice, but did pick out the parts that were especially meaningful to me (ego?).

Personally, I don't meditate, but could sit in a room for an hour by myself without difficulty. I've got a really great imagination. That's not what you're talking about, I know, but I easily achieve a state that is separate from wherever I am. A hypnotist once told me I was the easiest subject he ever had. And yet, I don't meditate. I get impatient with meditating. Maybe because meditating is a state of mindlessness, and I am totally lost in wherever I direct my mind. I don't empty it. I fill it.

I think your discussion of the Buddhist regard for the dead captures something essential about the difference between a scientific concept of being and the Buddhist concept of being. Basically, science doesn't address being. It looks for utility--if we can't measure it, see it, it's not there. Therefore, it has no value. I actually view this as dangerous.

The Buddhists remind me of the anecdote I heard about an elephant who lost her calf. She would not leave the side of the calf for days, although it was clearly not alive. She would leave occasionally to feed and scavengers would descend immediately. So she went without nourishment for days. To her the essence of her young one was still there. Like the Buddhists, she would not forsake her calf until extreme hunger drove her from its side.

I think it is a worthy goal to have a trained mind. The example of the self-immolating monk is persuasive. The important part is not to attempt to achieve that state because of its utility, but to achieve it for itself. Have to think about that :)

You do write long blogs, but they're unique and always ask us to think, for the good.

Thank you. Thank you. It motivates me how you judge my blog posts.

translated that from here

The natural sciences can only approach what is called "being" in an abstract way, but human experiences cannot be interpreted quantitatively. Everything a person has ever experienced, what he perceives, interprets, feels and thinks, is accustomed to, encompasses his entire life span and breaks its ground in moments when he is confronted with decisions. It is impossible to make the superstructure of the human psyche comprehensible by means of cut-out and isolated thought games. People decide, for example, on the basis of a chosen identity in one moment and on the basis of another identity in another moment. Depending on external conditions and inner resonance and reflecting thoughts or non-reflecting impulses to these conditions.

Some things simply lie outside the empirical measurability and thus outside the classical scientific experiment and investigation arrangement. In my opinion, the dangerous thing you are talking about is that nothing that is not scientifically verified may claim reason.

But if reason is only reserved for the natural sciences, then we do indeed have a new religion.

I suppose this is what you meant?

The anecdote about the mother elephant is a nice analogy to the wake. Thank you for this example.

That you pick out what produces the greatest resonance in you is interesting in the sense that one could say that you either feel inspiration there that is positively motivated. Or even lets a problematic aspect sound, in which you reflect what might still need to be contemplated, as you have also hinted. You could call it "selfish", but the ego is also a very good servant.

Everyone gets impatient with meditation. It's one of the most difficult things to do when one is not practiced. I train myself on being mindful (present to the moment and not on autopilot) but I am not a regular mediator myself. Still fearing the lack of being successful in it :-(

<Some things simply lie outside the empirical measurability and thus outside the classical scientific experiment and investigation arrangement. In my opinion, the dangerous thing you are talking about is that nothing that is not scientifically verified may claim reason

There is a saying, which I don't particularly like, "Render unto Caesar those things that are Caesar's and unto God those things that are God's". I think the concept may be applied to science. There are whole areas of concern where I insist upon the scientific method for validity. And then there are areas that science cannot possibly measure. It doesn't have the tools. Doesn't even have the ambition. We need the monks, and ourselves, to sort out questions of being. Consciousness is a kind of hybrid: science can measure certain values and certain I think will always be beyond its reach. The idea of "knowing" becomes profound. We know somethings because we can prove them. But knowing, as in awareness of ourselves and others--that's another matter.

As always a thought-provoking discussion. Just got up. Just beginning to drink my coffee and you awaken my awareness :)

@erh.germany You have received a 100% upvote from @botreporter because this post did not use any bidbots and you have not used bidbots in the last 30 days!

Upvoting this comment will help keep this service running.

Thank you.