Playing Out of Order: Part 3 (Do's and Don'ts)

A while back I examined the use of nonlinear narrative, especially with a focus on games, (part 1 and part 2 for reference). At the time, I'd thought about the issue somewhat, but I have a few concrete guidelines now for what looks like good nonlinear storytelling in games.

Oh, and if you missed the announcement, I'm also holding a game maker's competition. The first phase focuses on worldbuilding. Three winners will win 10 Steem each (or $30), so feel free to check it out and participate! It will run through June 20th, and you can find more details here.

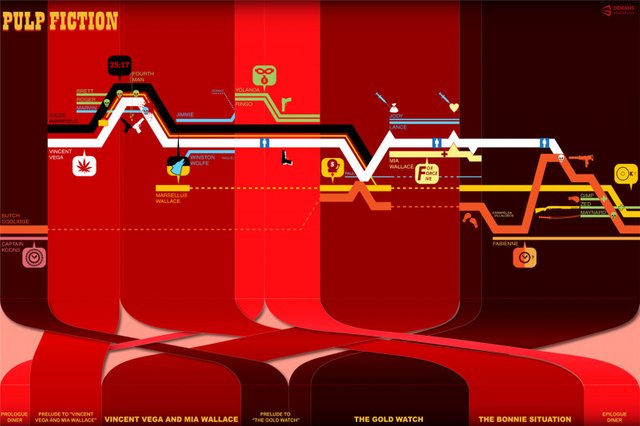

One of the good starting points to work with whenever you are trying to figure out how to do something well is to find a master and imitate them. For this purpose, I will be returning to Tarantino, and Pulp Fiction in particular, once again. I'm not going to to into many details, but I will be posting everyone's favorite infographic again, because it's useful.

Before we can really talk about what makes a good nonlinear narrative, we need to do some basic digging into narrative structure.

First, you have a simple plot outline that serves us well. The audience's interest will rise as the plot thickens, and you'll build up tension. At some point (unless you have a really rough cliff-hanger), you start to release that tension following a pivotal event, and things get back to normal.

This tension develops in a particular pattern: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, resolution. You need these pieces (or at least the first three, at the bare minimum) for the story to really hook readers, and you can't jump between them easily.

You also need to be working with characters who grow and develop; the Hero's Journey postulated by Joseph Campbell is so popular that I'm not even going to spend time explaining it here (though I have in the past).

As we move into a nonlinear narrative form, our big three goals should be to do the following:

- Keep the tension at an appropriately increasing (or falling) level.

- Don't mess up any of the stages of the plot; you can't go from the climax back to exposition without things feeling cheap (like doing a deus ex machina when it turns out that a character had done something off-camera in the first scene that made the final challenge moot).

- Show how characters develop and change over time.

Now, I'm not an expert on this; I've only experimented with it and observed it in play, but I have a few ideas for ways to do this.

A little goes a long way.

You don't need your nonlinear narrative to be comprised of a bunch of disjointed 20 minute segments shuffled around. You can do that, but it risks a fixation that can be problematic. Show bits and pieces as necessary; if you're going to have large chunks, there are a few ways around the issues.

In Pulp Fiction, some of the scenes are really small; the diner scene at the start of the movie is pretty short, while the Golden Watch prelude is a little longer.

Don't feel like you necessarily need to explain questions during a particular segment of narrative. This does increase the difficulty of following the plot, so it's important not to answer too many questions. Consider what the portion of the story you're in really needs. We just need to know the characters' personality and motivations, so focus on that.

Remember where you are.

The biggest piece of advice I can have is to remember where you are in your storyline. Dunkirk does this really well; each time we see characters at the beginning of the movie, we're being told about who they are and what situation they find themselves in at Dunkirk.

The best way to ruin a nonlinear narrative is to skip too far forward or too far backward. This is important to remember, because we have a tendency as storytellers to write stories in chronological order, and use earlier moments in a character's story to tell us about them.

You will torpedo your plot if you go from rising action back to exposition. You can maybe get away with a little nod or wink to the past, something that shows one pivotal moment coming together. I'm thinking of Guy Ritchie's Snatch as an example of this, but it's been a while since I've seen it and I'm not sure I'm remembering it correctly, and it's a comedy so more rules can be bent. One thing that helps is to observe the chronology of events.

You'll notice that in Pulp Fiction, for instance, each character is seen at the same stage of their story in sequence: we have exposition for one character, then another, then another, and so forth. Even though the events unfold out of order, we see things that tell us about the characters (for instance, the diner scene shows us Jules and Vincent's personalities, just as the Golden Watch shows us Butch's).

If you move too far, you'll give your audience tonal whiplash. The nonlinear narrative can actually be a great way to introduce a large cast if you're doing it right, or you can bring the whole storyline to a crashing halt.

Keep characters moving forward.

One of the issues I've seen where nonlinear narratives get frustrating is when a flashback doesn't show us anything interesting about a character. You can use a quiet, contemplative flashback in the resolution or falling action of as story to help show some trait of a character that has either been changed or came in handy (though avoid the deus ex machina method of showing that the character knew something, unless it fits your genre and tone).

The rule of thumb here is that flashbacks should be novel; they shouldn't show a character doing more of the same. A character like Solomon Cane, for instance, has lots of room for flashbacks that show us a new side of his troubled past: he could have a nightmare about something he did, for instance, but that's because he's on a personal journey of penitence and we may need more context on what exactly he's hoping to absolve himself of.

Application in games

So, I've had a hard time with most nonlinear elements in games.

Generally, the only tabletop roleplaying game that really springs to mind as having much of a discussion of nonlinear narrative that I'm familiar with is the Leverage RPG, which uses flashbacks as a way to explain what happened.

There are a few downsides of flashbacks and other nonlinear tools as you go through a game, however.

First, you need to consider the fact that characters may have changed a lot. Most players will be respectful in the sense of remembering that their characters have no knowledge of recent events in a flashback that goes before them, but gaining new gear or abilities can make flashbacks in particular pretty difficult.

Flashforwards run into difficulty when the characters wind up locking themselves into one path. This isn't hard in video games where there is a single linear plot, but in any other setting you're sort of tying yourself into a particular course of events, and players can accidentally or deliberately derail things.

Nonlinear narrative elements in games often do best in very subtle applications. You might want to dilute the mechanics, so that characters don't feel powerless in the context but so that you can have players have a distinction between the current character and their past form.

One thing that I think works well here is to ask players a simple question: "When the gates of the capital fell, what did you do?"

Handling the past has important narrative concerns, and generally you don't want a mechanical outcome to be the determinant in events. The less chaotic influences you have, the smoother the story will go.

Dealing with future elements in stories is possible, though dangerous. The point of using an interactive media is that you give the players agency and choice, so you don't want to take that away by showing them some grand vision of the future.

Instead, use hints and foreshadowing. The Elder Scrolls: Morrowind does this wonderfully, with the protagonist being basically forced to confront a series of troubling dreams and visions in order to find their true identity and overcome the challenges facing them and Morrowind as a whole. The elegance of having the future snippets be vague is important, but you can always show events that are outside the players' control anyway. For instance, once the players leave an area and have no way of returning, they can be offered a glimpse into the future, which shows an upcoming event in the place they have left.

The secret here is that these events should be something that is not dependent on the players' actions. For instance, they may see an army laying siege to their home city. This gives them the notion that they need to start preparing, but any course of action can still lead to this outcome. Being vague lets the storyteller weave in hints for the audience of what to expect, but not necessarily work in stuff.

Foreshadowing and flashbacks do not make a nonlinear narrative, however.

To really make a nonlinear narrative work for a game, you need more buy-in and you need to follow a structure. For instance, in a game with a bank heist plot similar to Reservoir Dogs, you could show the aftermath, then go back to the failed heist itself.

It is important to consider mechanics. Lighter storytelling-oriented games naturally do better at telling stories, but so long as you are careful not to have anything that could create inconsistencies you're going to be fine.

One final note here is that anything that takes place in the past is going to be better with little or no risk, as any permanent losses that occur will not be able to be undone without a magic hand-wave. You can still have high-impact scenarios: for instance, having the players take their space-ship to confront an alien menace, then at the pivotal moment breaking back to the negotiations for support planet-side to determine the outcome.

This is best not necessarily as a fore-ordained point in the story, but as something that comes up when the players are in a rub. They may be going out to risk their lives and sacrifice, but they could get help at the last moment from people that were convinced to help in the nonlinear interlude.

If used properly, this can avert disaster, allow characters to shine where they might not normally shine, and still tell a satisfying story.

Get your post resteemed to 72,000 followers. Go here https://steemit.com/@a-a-a