Using Archetypes: The Hero (and Co.) [Part 2: Not Quite Heroes]

Yesterday we talked about the Hero's Journey but today we'll talk about the various ways that the Hero's Journey will turn out with various types of hero.

This will give us a better understanding of what a typical Hero is, and how to play and subvert with notions of heroism when we are writing stories or playing games with characters that need to feel like they are part of a grand story that answers questions about reality and our existence, rather than just numbers and tags pretending to mean something.

1. The Standard Hero

The standard hero, who we discussed more heavily yesterday, goes through a standard hero's journey which takes them from an ordinary place to a supernatural world. Typically they return again to their home, though this may be a sort of metaphorical return: Thor in Marvel's Thor: Ragnarok, for instance, is a standard hero who winds up in a different home than the place he started in, but does so in a way that results in him returning to the things that he valued previously and improving them.

This is one of the characteristics of a standard hero, even if they seem to fail on the surface, they will end with positive change in their world.

It's worth noting that many of the other forms of heroes also fit the archetype of the standard hero, especially the epic hero.

2. The Tragic Hero

Anyone who's read Shakespeare as part of their course of studies is likely familiar with the notion of the tragic hero. Much like a run-of-the-mill hero, they will be placed into a heroic struggle, but unlike the standard hero they are typically strong and noble at the start. Shakespeare's Othello is a great example of this: a famous general who has overcome racial prejudice through sheer competence, he is quite an admirable figure at the start of the play.

However, the tragic hero's journey takes a twist along the way. Where a standard hero is subject to trials and temptations but succeeds, the tragic hero has a character flaw or some missing virtue that prevents them from being fully successful: they may make an honest mistake and not be able to fix it, but in the majority of cases their flaw is deeply moral and relates to their understanding of how they fit into the world.

By the time that the Supreme Ordeal comes to pass near the end of the Hero's Journey, the tragic hero has deteriorated from the realm of the noble to a certain pathetic level, where they are worthy of our pity.

Stories that involve tragic heroes play on our need for catharsis, the moment when we feel emotions vicariously, and serve as cautionary tales against vice and foolish behaviors. Many tragic heroes are very compelling, like Chinua Achebe's Okonkwo in Things Fall Apart, because they are people who seem valid figures of admiration on the surface—and it may even be that their flaws do not exceed their virtues—but have some hidden sin that destroys their ability to complete the path of the true hero.

3: The Epic Hero

The epic hero is another figure that is worth taking note of. They function a lot like a standard hero, but they have additional mythical qualities to them. The journeys they face and the adventures they have draw from their nature as something beyond humans, and many of the epic heroes interact directly with incarnations of the laws of nature.

It is not that the epic hero is incapable of failure; Odysseus, Gilgamesh, and Beowulf all have moments that either appear to be failures or are complete failures on their part, but it is rather that they have incredible abilities not available to every person.

The stories told with epic heroes have a special place in our psyche. Epic heroes often embody Jungian personality archetypes; Odysseus reflects the Sage, Gilgamesh reflects the Seeker, and Beowulf reflects the Ruler, for instance, when most modern heroes have a well-rounded basis in a variety of personality archetypes. Because of this epic heroes are most likely to encounter divine assistants to help balance them out, and many of the most memorable characters in epics are those that help the epic heroes and show a counter-point or magnification of the archetypes they demonstrate.

Epic heroes have a special role as moral instructors; they do not fail because they are models of an ideal life, one that mere mortals may not even be able to strive for. Of royal or divine blood, they illustrate stories of justice and injustice, good and evil, and other cosmic concepts beyond what can be done in the mortal realm.

4: The Anti-Hero

The anti-hero is not a true hero at all, but they are common enough in stories, especially modern stories, that any in-depth discussion on the hero archetypes and its variants would be lacking without mentioning it.

Contrary to the modern use of the term, most anti-heroes are not just heroes who do bad things. A traditional standard hero does not have a requirement to act in moral ways, though epic heroes almost always act in accordance with their moral code and tragic heroes are defined by the moments in which they do not.

Anti-heroes, however, fail to live up to their expectations. They are pushed into the Hero's Journey despite a lack of qualifying traits and suffer immensely along the way. At no point, however, do they develop the traits they need to be successful. This means that they wilt and wither, making poor decisions and eventually ensuring their own demise, typically in a social or psychological way.

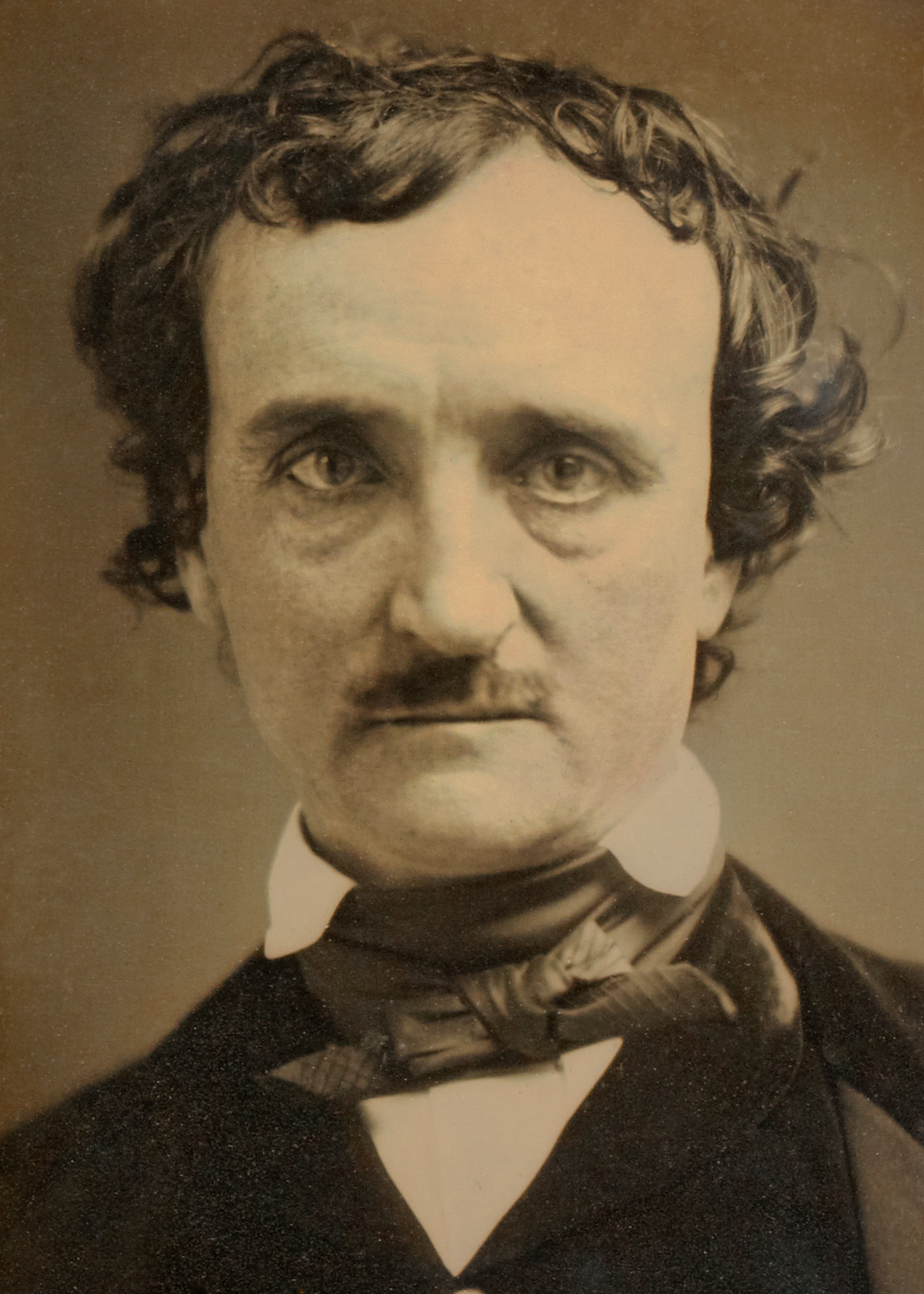

Poe had some of the earliest anti-heroes, with characters like the narrator of "The Tell-Tale Heart" and Prospero in "The Masque of the Red Death" serving as ready examples of anti-heroes, though in the modern day most anti-heroes are known to come from dystopian fiction, like 1984 and Brave New World.

A daguerreotype of Edgar Allen Poe, unknown photographer, public domain

The anti-hero is a failure, and unabashedly so (at least as far as the writer's intent toward them goes). They never had the means to accomplish what they set out to achieve, and their failure is totally a product of their own nature.

While the tragic hero goes from noble to ignoble, the anti-hero starts out as a loser and stays there. They do follow the traditional Hero's Journey up to the Supreme Ordeal, much like the tragic hero, but the anti-hero does not have the tools to succeed upon the way even if they tried, unlike the tragic hero who usually has to make a mistake to fall afoul of their worse parts.

Applying this to Writing and Games

How can you use the various hero archetypes in writing and game design? It's actually pretty simple:

Know what story you want to tell.

Each type of hero serves as a compelling back-drop (if done right; bad anti-heroes are a scourge of the modern literary scene), so it is simply a matter of choosing the heroic archetype that fits the theme and message of your story.

The Standard Hero

A standard hero is pretty common in literature because it's feel-good stuff, and because in the day-and-age of mass publication having a character that survives and earns a sequel is pretty much a gold mine. These standard heroes are still able to be sympathized with, but not falling victim of their flaws (or working past their flaws over time, which can be an even more compelling narrative of triumph and success than the stories authors intend to tell).

For a game designer, the standard "grow up and get stronger" method favored by pretty much every game on the planet (D&D springs to mind, as well as most of the games heavily favored by it) work really well for standard heroes, and players don't have a hard time stomaching the archetype. In fact, most designers don't really factor in the whole design mindset of the hero's journey, and the final parts after the Supreme Ordeal usually wind up being filled in by the players and game masters playing the game. Adding some end-game mechanics to allow for characters to be rewarded for their success is a perfectly good idea.

The Tragic Hero

Tragic heroes do a great job at telling moving and memorable stories. Human life tends to be inherently tragic: we live for a time and we all die, and by living a good life we are only able to minimize the flaws (which are not in our stars but in ourselves) that make life even worse than it has to be. That doesn't mean that life is not worth living, since there are treasures and merits to be found out there.

But tragic heroes lose their way, either forgetting the good that exists in the world or not dealing with their flaws. They are romantic; we see a part of ourselves when we fail in them, and it's sometimes easier to root for them than it is to root for a hero who has had a good string of successes and feels too much unlike ourselves. We're all just a few bad choices away from being tragic, so the archetype is quite powerful as a reflection of what we could become.

The tragic hero is a more difficult archetype to use in games, because you need to have a mechanic that compels a fall. This can be seen as a betrayal by players, and it is something that needs to be done carefully and with full cognizance. White Wolf's Vampire: The Masquerade does this quite well, with protagonists who are vampires trying to survive, typically wanting to balance their humanity and old identity with the alien, predatory creatures they have become.

By creating plenty of ways to fail, a game designer can move systems away from the traditional "grow to be a god" style of D&D toward a more tragic approach, especially if characters have permanently dwindling resources or can make decisions that permanently mark them. Rowan, Rook, and Decard's Spire (affiliate link) is a great example of pulling this off well.

The Epic Hero

The epic hero has fallen somewhat out of favor. It is hard to write a good epic hero, especially since many of the classic epic heroes thrive by going out into the unknown where there is no longer any mystery. The suspension of disbelief is lacking, even if those classic tales are so well-spun that they continue to captivate audiences, so most modern attempts at epic heroes fall short of their goals.

However, the most powerful element of the epic hero is in the form of sacrifice. The best example of this is Beowulf, who goes out to slay a dragon once he becomes king, even though it will almost certainly be fatal for him because he is no longer the young and ready hero he once was.

This willing sacrifice is the core concept of the Christ narrative, and when it is played out in a fully realized and developed manner it can be as compelling and relate as closely to our modern lives as any other heroic archetype's activities does.

So as a game designer, if you want to tell stories about epic heroes, give them an unknown, give them danger, give them a cause to sacrifice for. This will give them the power to feel meaningful even as they stray from the humanity that we connect to.

The Anti-Hero

The anti-hero is probably a harder hero type to write. It's not that there have been a dearth of anti-heroes throughout history, they just tend to make pathetic and uninteresting stories if not written by an expert who has dedicated themselves to the craft.

Anti-heroes exist as cogs in the machine or worse, and they are the most ready embodiment of a normal person you will find in storytelling: flawed and desperate.

The great thing about anti-heroes as a game concept, however, is that they don't outshadow each other. Where normal heroes need to be carefully defined roles and given competence and aptitude that doesn't trample on each other, if everyone is incompetent in at least one significant way, as anti-heroes are prone to be, they are forced to work as a group. Paranoia does an excellent job of this as a game, both by fostering an actively hostile inter-player relationship to simulate the moral flaws of the anti-hero, but also ensuring through mechanical and narrative means that most characters will fail even if their players make virtuous and cooperative decisions.

Two-Minute Breakdown

The standard hero follows the Hero's Journey as we previously discussed, but the tragic hero follows a reversed curve where they end broken after starting mighty. Epic heroes tell great cosmic archetypal stories by being larger than life, while anti-heroes tell very plain everyday stories by being no better than an average person, and in fact worse in some ways.

Congratulations @loreshapergames, this post is the most rewarded post (based on pending payouts) in the last 12 hours written by a Dust account holder (accounts that hold between 0 and 0.01 Mega Vests). The total number of posts by Dust account holders during this period was 5432 and the total pending payments to posts in this category was $680.64. To see the full list of highest paid posts across all accounts categories, click here.

If you do not wish to receive these messages in future, please reply stop to this comment.

Congratulations @loreshapergames! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

To support your work, I also upvoted your post!

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPDo not miss the last announcement from @steemitboard!