The infinity of Asterion — Part III

The first two parts of this analysis about the story "The house of Asterion" by Jorge Luis Borges have had an introductory character. In the first part we have put attention to certain aspects present in Borges' work and in particular to the metaphorical use of the labyrinth, while in the second part we have made a brief review about the concept of infinity, a concept that is usually linked to the image of the borgian labyrinth. Both introductory parts form the basis for the study that we propose here.

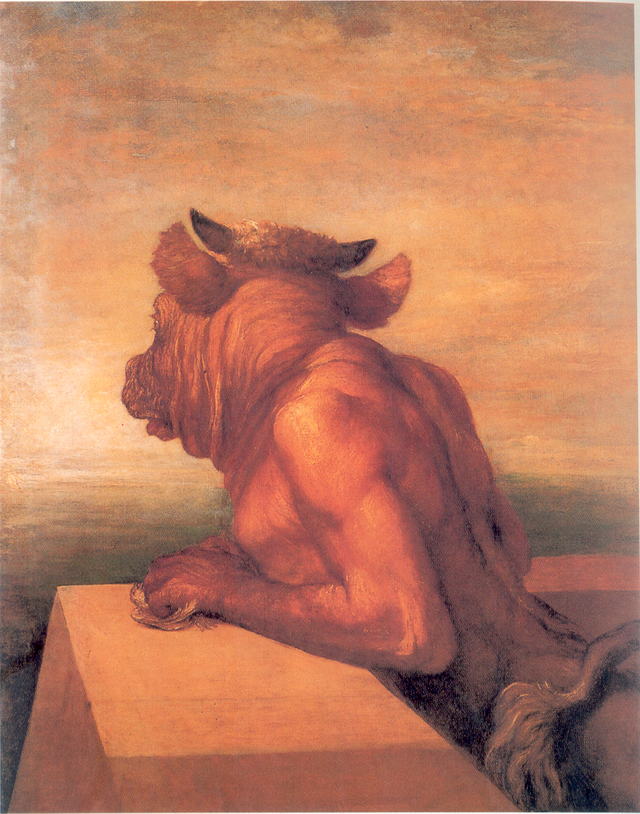

With this third part we began the analysis properly, which may be advisable to read this short but intense Borges´ story, as well as review the Myth of the Minotaur.

THE MULTIPLICATION OF VOICES AND THE PROLIFERATION OF SENSES

Polyphony and intertextuality constitute one of the most notorious and frequent features in the work of Borges. As we will see, the story that we have to analyze is not an exception.

Polyphony

In terms of polyphony, the most obvious mark that the story presents is the presence of two narrative voices; even, the passage from one to another is indicated typographically with a white between paragraphs. The narrative voice with which it begins, and which covers most of the text, is that of the protagonist (first person). With it the reader is presented with the internal vision of Asterion; he is discovering his inner world and his particular way of perceiving and understanding the outside world.

But in the end of the story this voice is silenced to make way for an omniscient narrator who with only one phrase, descriptive but clouded in poetry, refers to the battle that puts an end to the life of Asterion in the hands of Theseus and then he makes the voice of the same Theseus intervene in the form of a direct speech addressed to Ariadna: "Will you believe it, Ariadna? —Said Theseus—. The minotaur barely fought back”. It is not until this final intervention that the hypertextual relationship that the story has with the myth of the minotaur is revealed.

Anderson Imbert (1960) in his study of the story aptly indicates: "If we recognized the myth, the house of Asterion would not have surprised us. How did Borges keep us in the dark until the last line? He simply adopted the riddling procedure: he showed all the keys but the only words he did not mention were, precisely, labyrinth and Minotaur”.[6]

We see then that the voices of the two narrators are pronounced from two perspectives that confront each other. The voice of Asterión presents the protagonist from his own experience; we discover a lonely, and maybe misanthrope, who wanders through a house in which everything is repeated endless times, which performs various games (among which is imagining the company of his other self) to deceive his loneliness and wait for someone who redeems it from that existence. He is superb, he defines himself as unique and superior, but at the same time he is exposed to a certain vulnerability, he suffers his isolation. Asterion appears here on his human side and the reader tends to identify with that individual lost in an infinite universe that fails to understand.

But with the final intervention of Theseus appears a second perspective, which corresponds to the mythological view, in which the minotaur is just a beast that does not merit any mercy. Theseus is astonished by the little resistance offered by the minotaur in the battle, but he does not know the "human" reasons that led the minotaur to such a docile surrender.

Intertextuality

As is often the case with Borges's texts, in their re-readings intertextual winks appear that at first could have been overlooked, with which the story is enriched while the voices multiply and with them the ways of interpreting the reality.[7]

In the first place, there are several references that reinforce the hypertextual relationship of the story with the myth (which, as we said, Borges always tries to disguise with the purpose of veiling us until the end this identification of Asterion with the minotaur). The first references to the myth arise from two paratexts: the title, in which the name of the protagonist is made known: Asterion (this is the proper name, and little known, that in the Mythological Library Apolodoro gives to the minotaur), and the epigraph that is an appointment of said book (appointment that nevertheless appears modified in order to hide the identity of the character).[8]

Also in the text are indications that refer to the hypertext. Two times the temple of the Axes is mentioned ("Some climbed to the stylobate of the Temple of the Axes" and "I have seen the Temple of the Axes"), a term with which it seems to be referring to the palace of Knossos in Crete, which is the Greek island where, according to mythology, the minotaur's labyrinth was located. And at the end of the first paragraph, confirming what is indicated in the epigraph, the same Asterion is defined as the son of a queen: "it was not in vain that my mother was a queen".

Note also that in relation to the description of the house, although the word labyrinth is never mentioned, several indications lead to think about it. It is said that "its doors are open day and night" and that "there is not a single piece of furniture"; Galleries, corridors, crossroads, bifurcations are mentioned. And when in a parenthesis it is indicated, to reinforce the unique character of the house, that "(those who declare that there is a similar one in Egypt)", we can think that he is referring to the labyrinth that according to Herodotus was next to the Meris (a large lake in the The Faiyum region, Egypt). This parenthesis, in addition to referring to the house as a labyrinth, has the imprint of what could be an intertextual replica directed to Herodotus. It is read in the book of Herodotus: "I will dare to say that anyone who crossed the strengths, walls and other factories of the Greeks, who show off their greatness, none will find among all that is not minor and inferior in coast and in work to said labyrinth”.[9]

But it is coming to the end of the monologue that identification with the myth is becoming more obvious. In the last paragraph of the parliament reference is made to the young men who according to the myth were sacrificed (although the number of them differs, in the myth they were fourteen): "Every nine years nine men come to the house so that I can free them from everything wrong"; and in the epilogue of the monologue, when Asterion asks himself what his redeemer will be like, his own nature is suggested: "How will my redeemer be?, I ask myself. Is he a bull or a man? Could he be a bull with the face of a man? Or will he be like me? "(Note that the combination that needs to be mentioned and that would take the place of the last question is that of the minotaur: a man with the face of a bull).

All this reinforces the presence of two perspectives that confront, two different and opposed ways of interpreting a reality. However, after this analysis we see that these are not limited to being represented one by the voice of Asterion and the other by that of Theseus, but that this opposition is present throughout the text; from the paratexts to the monologue itself of Asterion appear as a dialogue between the story and the myth (between Asterion and the minotaur). Even in the final intervention of Theseus, with the surprise that he manifests before the almost passive attitude of the minotaur, this double perspective is present. In this way, the story and the myth are feed back into a dialogue that lasts indefinitely while new foci of discussion are created that orbit the thematic axis, diversifying and multiplying the senses.

There are two other intertextual allusions in the story. One that refers to Plato's Phaedrus —Bratosevich warns about the use that Borges makes in his texts of the "Platonic ingredient", questioning his exclusion by Jaime Rest in pointing out in his essay the nominalist aspects of the writer—[10], with the phrase: "like the philosopher, I think that nothing is communicable by the art of writing". Remember that Plato in this dialogue makes Socrates say that through writing only transmits "appearance of wisdom and not true wisdom" (Plato: 1983, 365).

This intervention occurs in the second paragraph of the monologue, in which Asterion confesses that he can not read or write. One may ask then who the narrator really is, who puts in writing the words spoken by him. It is evident that as readers we are accessing the words of Asterión in a mediated way.

Of course, in advance we understand that it is a fiction; but it is within the fiction itself, already accepted by the reader, that he rediscovers that he is not a direct witness of what is referred to by "Asterion narrator", but that his expressions come to him, in the best of cases, as the translation which makes them some privileged witness.[11] The narrator does not identify himself; it is hidden behind the name of Asterion, but it is not Asterion. The reader is thus discovered in front of a voice that is a translation or interpretation of another, which accentuates the polyphony of the text.

The other statement with intertextual content is: "because I know that my redeemer lives and finally will rise on the dust", with which the book of Job of The Old Testament is alluded to where it can be read: "I know that my redeemer lives, and at last it will rise on the dust "(Reina-Valera: 1960, 777). As we see it is a plagiarism, that is, an undeclared but literal loan.[12]

Finally, we must not forget the footnote in which a supposed editor appears correcting or reinterpreting the fourteenth word, which mentioned Asterion, by infinity. This unique paratextual reference will be discussed in detail in the next section. Observe, however, that this footnote implies a second mediation between the words that Asterion would have pronounced and the reader: a supposed editor appears correcting the original that would have been written by someone who witnessed what was said by Asterion.

The unapprehensible reality

This analysis allows us to see the polyphony that presents the text that starts in the first place of the narrators, the characters and the author himself; which is increased through the intertextual game to which, with extraordinary erudition, Borges submits. These voices coexisting in the text are carriers of discourses that discuss or dialogue with each other; what produces in the reader the sensation of being in front of a reality that can always be reinterpreted; that by not allowing themselves to be reached by any conjecture, they proliferate, multiply, confront or succeed one another, without ever finding a term.

[6] Anderson Imbert, “Un cuento de Borges: «La casa de Asterión»”, Revista iberoamericana, 36.

[7] Beatriz Sarlo points out this characteristic of Borges's writing as an innovator in her time: "Borges anticipated topics that today absorb literary theory: the referential illusion, intertextuality and the ambiguity of meaning (or its proliferation)”. (Sarlo: 1995, 44).

[8] In Apolodoro's version it reads: "Then that one (Pasiphae) gave birth to Asterio, the so-called Minotaur; It had this bull face and the rest of man". (Apolodoro: 1987, 75).

[9] Heródoto de Halicarnaso, “Los nueve libros de la historia: libro II”, Wikisource. Available in: Los nueve libros de la historia.

[10] Nicolás Bratosevich, “El desplazamiento como metáfora en tres textos de Jorge Luis Borges”, Revista iberoamericana, 549-560.

[11] The intertextual connection with the dialogue of Plato, could be interpreted as an insinuation of a certain dialogical nature that veiledly seems to be found in what in the story is presented in the form of a monologue.

[12] Borges said in a conference published in Seven Evenings: "The idea of God as indecipherable is a concept that we already find in another of the essential books of humanity: in the Book of Job. You will remember how Job condemns God, how his friends justify him, and how God finally speaks from the whirlwind and rejects equally those who justify him and those who accuse him. [...] God is beyond all human judgments and so declares himself in the Book of Job" (Borges: 1980, 26). Then, Asterión and Job are both identified as individuals lost in an infinity: in the universe the first one and in the divinity the second one.

Me sentí ignorante, pero maravillada con lo que planteas; cuando no tenemos el conocimiento para analizar una obra, peor aún, cuando no hemos leído la obra, está clase de aportes generan intriga, incógnitas en el cerebro que dicen: "léelo para que entiendas como se rinde un minotauro de manera dócil" 🤔

jeje. El cuento es corto y muy recomendable. Bueno, todo Borges es muy recomendable.

Y este estudio me llevó largos meses realizarlo, pero me ha entretenido mucho hacerlo. Tiempo atrás lo publiqué en español: El infinito de Asterión