Tree of Life: End of the Line

Let's see if I can squeeze a post out before England comes home in a few hours. It'll be a short post, kind of a pre-post to the upcoming finale.

Recap

Last time I discussed one thing that makes us Great Apes unique among the rest of the animal kingdom, particularly among other mammals: Colour vision, particularly in the form of Trichromacy. We originated with tetrachromacy and dropped two sets of colour genes to end up with dichromacy but only apes managed to re-evolve a third pigment gene to give us the vision we enjoy today.

But one other thing I pointed was how much trouble taxonomists were having putting animals into separate groups. What makes one group of animals unique to the rest enough that they can get their own special category? For Apes it's kind of difficult because although most apes have obvious distinguishing features, almost all of them can be seen in at least one other non-similar mammal, and, well, it just gets complicated.

So how are apes categorised?

The Road to Humanity

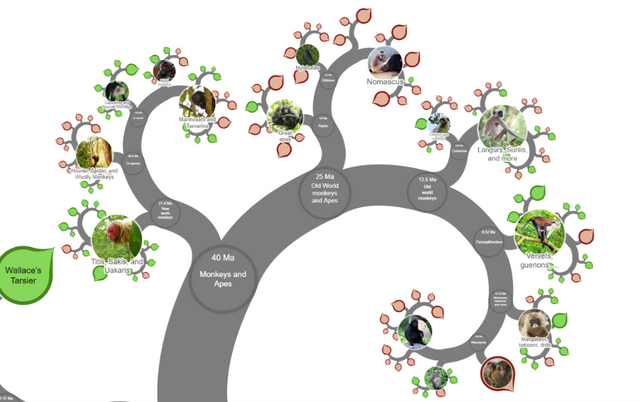

About 70 million years ago, animals like treeshrews and lemurs broke off and left us in what we call the 'Primate' group. From here, Tarsiers broke away about 60 million years ago, and 40 million years ago saw the departure of New World Monkeys.

The blink of an eye, that.

Catarrhini

More recently about 25 Mya, we ironically grouped things into 'Old World Monkeys', within the Catarrhini clade, which translates literally to 'down nose', referring to our downward facing nostrils rather than our obnoxious outlook on the rest of nature. Apes are a sister group with Old World Monkeys within this clade. Our collective flat noses turned out to be the defining feature that separated us from the New World Monkeys, who were described as 'flat nose' or platyrrhines.

But Catarhhines also lack prehensile tails - no exception, surprisingly. We also have fewer teeth with only 8 molars instead of 12, flat fingernails, substantial sexual dimorphism and a few other features as such.

At this point in the evolutionary tree, you can turn right and follow evolution to things like baboons and macaques, but turning left will bring you to the Ape category itself around 18 Mya.

Hominoidea

All apes, be it lesser or great, are native to Arica and Southeast Asia. As you may understand, apes are not actually an old world monkey, but a sister to them. Apes evolved a new form of transport some 18 million years ago called Brachiation - Arm swinging. You see this most famously among the gibbons which you can enjoy here:

Oh wait, maybe that was a human... well google Gibbons yourself, they're amazing and spend 80% of their entire lives in this state of brachiation.

Gibbons are the only extant species remaining that are true brachiators and apes only function as 'modified' brachiators (see above). This is because, though we're not very much designed for it, evidence does make it somewhat clear that our ancestors enjoyed this superior method of locomotion, such as our ball & socket shoulder joints and grabby hands.

I guess we just found it easier to lumber around on our hind feet at frustratingly slow speeds.

Hominidae

Here we have our next and penultimate step to humans. 14 million years ago, this family evolved and today only 8 species still exist, which you can probably name from memory. Have a go before checking below:

- Humans

- Sumatran Orangutans

- Bornean Orangutans

- Tapanuli Orangutans

- Eastern Gorillas

- Western Gorillas

- Chimpanzees

- Bonobos

Gorillas split first around 1.78 million years ago, followed by chimps about 1.6 along with the bonobo thanks to a river divide causing speciation between them. Orangutans, although only 1.3 million years in the making, spit from an earlier ancestor that split from us over 16 million years ago. This means that the three Orangutan species are the only great apes that do not fit into the final category: Homininae

And here we are. End of the Line.

From here there are no more groups, just You, Me, the Chimp and Bonobo. This is an unsatisfying end to this series since we still haven't managed to define humans specifically apart from chimps and bonobos, and to a lesser extent, gorillas. So this is something I'll finish the series off with next time.

I want to end today with a sobering sight on the reference website I use to follow the tree down to the end:

Extinction

Somewhere along the line towards the end, everything started looking pretty endangered, so I browsed around the area and this is what I found according to their conservation status:

- Humans - Least Concern

- Sumatran Orangutans - Critically Endangered

- Bornean Orangutans - Critically Endangered

- Tapanuli Orangutans - Critically Endangered

- Eastern Gorillas - Critically Endangered

- Western Gorillas - Critically Endangered

- Chimpanzees - Endangered

- Bonobos - Endangered

- 13/17 Gibbon species - Endangered

- 4/17 Gibbon species - Critically Endangered

The list goes on as shown by the red leaves below:

Zoos are gonna be pretty boring for our grandkids, that's for sure.

References:

Catarrhini | The lorisiform wrist joint and the evolution of “brachiating” adaptations in the hominoidea | Hominidae | Onezoom interactive tree

The endangering of our littermates is less dire than the actual extinctions that have occurred amongst our ilk in the genus Homo. Denisovans and Neanderthals seem not really to be species separate from H. sapiens, but subspecies or races. Not really sure about H. floriensis (hobbits), but they seemed to not inject themselves into our genepool, and also seem worthy of their own bit of the world, Flores (which they could share with dragons! I kinda like the idea of Hobbits, Dragons, and Giants having a place in our world).

I suspect I am more than 4% Neanderthal, actually. Denisovans seem to have made a giant impact on folk from N. America to Micronesia (like Heidelbergensis the remains we have of them appear to have regularly exceeded two meters in height).

But the power to restore extinct species also looks to be falling into our grasp and the loss of our closest relatives might be one of the likeliest to rectify first, as we have so much of their DNA in our own veins. Given the survival of so much Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA, and that none of H. floresiensis seems to have made it, do you think bringing back Neanderthals as a species has merit? I do see that H. Floresiensis does, as, again, they seemed to be pretty much confined to Flores, and didn't make the melting pot H. s. sapiens turns out to be.

Just curious, as I sure don't want to tolerate the loss of the presently endangered and likely to be lost primates you list. Hobbits seem meretricious as well. Given technology and how easily we can improve our development that has mostly been the cause of extinctions, I see that many species once considered forever extinct may be merely temporarily on hiatus.

Thanks!

Edit: development has been the cause of most of the extinctions that can be laid at the feet of Humans, I should say, not all extinctions.

Hey @valued-customer

Here's a tip for your valuable feedback! @Utopian-io loves and incentivises informative comments.

Contributing on Utopian

Learn how to contribute on our website.

Want to chat? Join us on Discord https://discord.gg/h52nFrV.

Vote for Utopian Witness!

I'll have to find time to look into Utopian more deeply, as I originally thought it to be something for devs, and I am not a coder.

Thanks!

Hi thanks for the detailed, well-thought response. I believe I am likely to be part neanderthal too, and this is one reason I don't think we should bring them back.

They didn't go extinct as a result of some thoughtless thing we did, they were simply bred away into the final result that is us. I am for bringing back animals that we are entirely responsible for unnecessarily wiping out, but otherwise, I see no merit other than experimental curiosity, which I don't think life should be used as a tool as such - especially if something as sentient as a neanderthal.

On the other hand, if it was something like a mammoth which seems like one of the more likely experiments to bring back, I think this is ok and does have some scientific merit. There is space and in fact, much of their previous environment is still somewhat intact. Create a space for them and I see little problem with this. But Neandethals, nah. Let them exist in the past with dignity

I completely agree, except I want the giant drumsticks that bringing back T. rex would provide =p

See, if I had it my way a LOT more of steemit would be depressing as hell environmental posts. Well done!

A lot of my posts I've made sure to end on a strikingly depressing note, lol. It's what I'll be known for upon my death, Hopefully. But probably not because we're all going to suffocate from CO poisoning.

Hi @mobbs!

Your post was upvoted by utopian.io in cooperation with steemstem - supporting knowledge, innovation and technological advancement on the Steem Blockchain.

Contribute to Open Source with utopian.io

Learn how to contribute on our website and join the new open source economy.

Want to chat? Join the Utopian Community on Discord https://discord.gg/h52nFrV

To listen to the audio version of this article click on the play image.

Brought to you by @tts. If you find it useful please consider upvoting this reply.

It is quite remarkable how a human body can adapt to nature through several millions years and survive till now.So we are the best among the best.

Finally something short enough that I can read without taking a break!

Yeah but not enough words to get into any meaty stuff I actually find fascinating. Just a precursor to the next post =P